Intro: Beat features

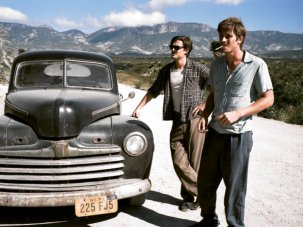

In a moment of genuine power and heart-rending revulsion towards the end of Walter Salles’ long-awaited, recently released adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s 1957 generation-defining roman-a-clef On the Road, Sal Paradise (Sam Riley), the film’s narrator, lies prone, delirious with dysentery in a dingy Mexico City brothel room at the end of his travels across the wide-open expanses of America. In his hour of need Sal is callously abandoned by the film’s protagonist, his restless and rootless friend and animus Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund). The trauma of that abandonment triggers feverish hallucinations. Sal recoils in abject horror as the reptilian phantasm of the pistol-wielding junky writer Old Bull Lee (improbably and, at times, almost convincingly played by Viggo Mortensen) manifests in the room before him. Leaning over Sal, Lee creepily insinuates in his croaky Mid-Western drawl, “you can’t deny your blood, kid – you’re white, white, WHITE.”

Yet Old Bull Lee’s line is neither scriptwriter José Rivera’s nor Kerouac’s. It’s quoted from the opening sequence of Towers Open Fire, Antony Balch’s 1963 experimental film with anti-novelist and Beat mentor (and the real-life Old Bull Lee) William S. Burroughs, although the text itself originates in Burroughs’ 1961 anti-novel The Soft Machine. In his parody of white Southern Puritanism, Burroughs is invoked as the unconscious nagging voice of Sal’s conservative upbringing.

Such references might seem no more than a game for dilettantes. Yet arguably all Beat feature-film adaptations (particularly the holy trinity: On the Road, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman’s 2010 Howl and, for my money the best of the three, David Cronenberg’s irreverent reinvention of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch) must take recourse to the era’s raw source material for impact, for their makers can rarely draw on such intensely lived experiences as those of the original creators.

William Burroughs and Matt Dillon in Gus van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy (1989)

My own introduction to Beat cinema coincided with my discovery of its literature late in 1992. A short time after a friend pressed into my hands a copy of Burroughs’ anthology of eerily perverse early short stories, Interzone, and immediately hooked me, I was amazed to see Uncle Bill himself playing Matt Dillon’s junky mentor in Gus Van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy (1989). Not long after I saw Naked Lunch and sought out as much as I could find of Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg (the poet referred to in On the Road as Carlo Marx, played by Tom Sturridge) and their contemporaries: texts that marked the post-war ancestry of the countercultural revolutions of the 60s and 70s. Yet somehow I found the movies never matched up to the rawness of the originals. Why?

As my new-found love of cinema grew alongside my obsessions with underground literature and the avant-garde arts, I gradually came to realise there was another independent cinema under the radar, most of it hard for a small-town teenager to see and which I read about in books and magazines, trying to imagine what it was like. This cinema was like the books – made with a spontaneous, hedonistic experimentalism in search of visionary experience. What this cinema is all about is reportage – documenting lived experiences both external and subjective, in the search for poetic enlightenment; something seldom channelled into industrial 35mm feature productions. For the filmmaker seeking freedom from commercial pressures, a simple solution came in the form of amateur formats, cheaper production values and cooperative distribution.

East to west coast: early awakening

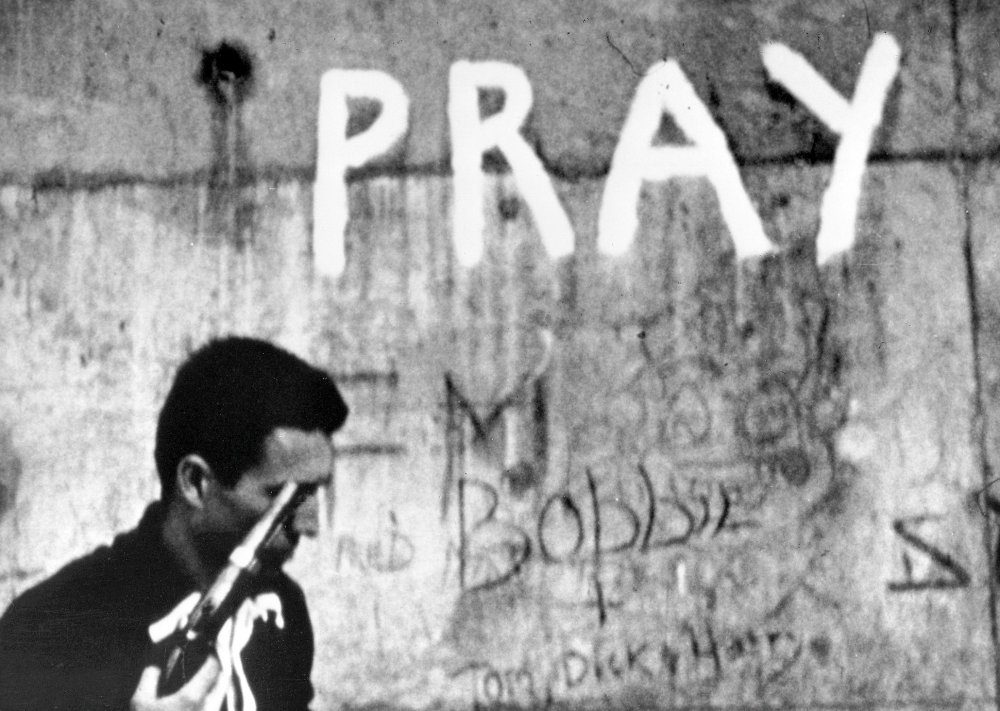

Stan Brakhage’s Desistfilm (1954)

In the summer of 1947, as documented in On the Road, Kerouac passed through Denver on the coattails of his friend Neal Cassady (the real Dean Moriarty). Local boy Stan Brakhage, a future leading light of American experimental cinema, was just 14 – but Kerouac’s influence would make itself felt in one of Brakhage’s first works, Desistfilm (1954), a seven-minute “explosion of the Denver beatnik nerves”, as Brakhage would note. Shot on four rolls of 16mm gun-camera film left over from the war, it deploys shaky handheld camerawork, a buzzing soundtrack and shadowy lighting to build an intensely paranoid atmosphere around a group of furtive teenage beatniks cooped up in an apartment room. It was influenced, according to Brakhage, by De Sica and Italian neorealism, yet it’s pervaded by an anxious sense of the uncanny. Brakhage would later acknowledge a debt to Surrealism, via Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950), though one suspects the emerging Cold War with its looming atomic bomb may have played its part.

In the early 1950s, the teenage Brakhage had already made his way down to San Francisco, where Kerouac had himself headed from Denver, years earlier. His intention was to study film at the San Francisco Art Institute under the pioneering experimental filmmaker Sidney Peterson, but by that time the course had disbanded and Peterson was gone. During his stay in the city Brakhage took the basement room of Peterson’s collaborator, the poet James Broughton. (The latter was away in London’s Crystal Palace, making his whimsical picaresque The Pleasure Garden (1953) [filmstore] with Free Cinema stalwarts Lindsay Anderson and Walter Lassally – and, improbably, British comedy actors Hattie Jacques and John Le Mesurier.)

One lament about the Beat Generation is its male domination. Yet Carolyn Cassady (née Robinson) – Kirsten Dunst’s ‘Camille’ in On the Road – was the reason the major Beat figures congregated in San Francisco. An exceptionally gifted painter and writer, she moved there in the late 40s while waiting for a Hollywood costume design job to come through. Neal followed her there to marry her. Kerouac visited. Ginsberg stayed until the end of the 50s, and would write and eventually publish his notorious epic poem Howl there, famously reading it in public for the first time in the city’s Six Gallery in 1955.

Chris MacLaine’s The End (1953)

Christopher MacLaine, a fellow poet and filmmaker whose tragic life ended in a mental institution, might have been present that evening. Brakhage, who knew MacLaine while in San Francisco, describes an artist who, while courting the madness that destroyed him, was also the “source of the Beats”.

MacLaine’s greatest work is his first film The End (1953), a raggedly apocalyptic 35-minute patchwork of deliberately amateurish scenes in the lives of a clutch of lonely, suicidal souls, which charts with sardonic irony the self-destructive urges of a generation under the threat of nuclear annihilation. Improbably, the film’s shaky camerawork is by the visionary filmmaker Jordan Belson (whose sublime optical abstractions can be seen in the 1983 adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s space-pioneers novel The Right Stuff). Only MacLaine could have directed such a spiritual filmmaker to shoot in such a nihilistic fashion.

As the 50s drew to a close, Ginsberg left San Francisco and returned (via Morocco and Europe) to New York – following the direction of travel set by the experimental filmmaker and artist Harry Smith, who’d ventured East after receiving a Guggenheim Grant. In San Francisco he’d been working on optical abstractions in a similar manner to Belson, frequently projecting his work behind jazz bands and with poetry in a foretaste of 1960s light shows. In New York, though, he moved into collage work inspired by mystical and alchemical subjects, a style he described as “semi-realistic animated collages”.

Return to New York: the New American Cinema

Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie’s Pull My Daisy (1959)

Brakhage had arrived in New York in 1954, not long after completing Desistfilm. Short of money, he stayed in the Greenwich Village apartment of experimental filmmaker Maya Deren (by this time a practising voodoo priestess, having just returned from her unsuccessful attempt to make a film about Haitian voodoo rituals on a Guggenheim grant). Deren, though, didn’t take to Brakhage’s filmmaking, nor to that of his emerging contemporaries, in which the element of chance and spontaneity played a much greater part than her ideals would allow.

Indeed, many Beat films were becoming increasingly abstract or, influenced by post-bop jazz, improvisational. And while the established experimental film society of the time, Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16, refused to show their work, others took an interest. The same year Brakhage arrived in New York, Adolfas and Jonas Mekas founded Film Culture magazine and Jonas began holding his own screenings and taking responsibility for distributing the best available prints – endeavours that would ultimately culminate in the creation of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative in 1962.

The Mekas brothers had arrived in New York late in 1949 as refugees from Lithuania. Within weeks they’d borrowed money to buy their first Bolex camera and immediately began filming the curious new world that surrounded them. They filmed themselves goofing at home in Williamsburg, Brooklyn and shot the immigrant communities of which they were a part. Famously, Jonas has continued to keep a film diary all his life, frequently cannibalising it for films such as Lost Lost Lost (1975), which spans 1949-63 and the brothers’ initial anomie and loneliness in their new culture to acceptance and integration with a community of like-minded bohemians such as Ginsberg, Ken Jacobs and Robert Frank.

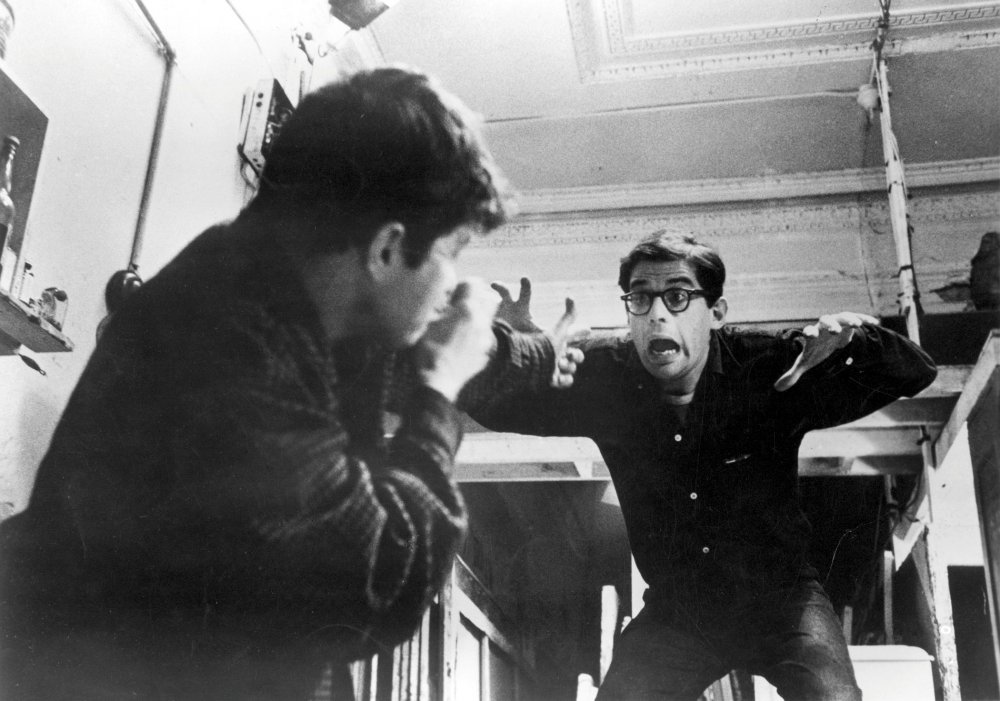

Curtis Porter recording the soundtrack for John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959) with help from the director

In Film Culture Mekas championed what he called the ‘New American Cinema’, some of the earliest examples of independent American films as we might think of them today. The magazine awarded its first Independent Film Award to John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959), funded from Cassavetes’ earnings as a mainstream movie actor.

Like Shirley Clarke’s subsequent The Connection (1961), Shadows focuses on Beat lifestyles, music and concomitant social issues. It charts the struggles of black New York brothers Hugh (Hugh Hurd) and Ben (Ben Carruthers) and their friends, culminating in a racist encounter with a man who’s dating their mixed-race sister Leila (Lelia Goldoni), whom he mistakes for white. The acting was improvised with the drama playing out to a hip, moody jazz score by Charles Mingus.

Mekas’s second annual award went to Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie’s Pull My Daisy (1959), based on an excerpt from Kerouac’s then-unpublished 1957 play The Beat Generation. (The film had to be retitled after MGM brought out an exploitation picture of the same name that year.)The story is a comical scenario based on a factual incident that occurred in 1955. Neal and Carolyn Cassady were expecting a polite visit at their California home from a local bishop and his elderly mother – only for Kerouac, Ginsberg and his lover Peter Orlovsky to arrive and fool around drunkenly, asking the bishop absurd theological questions.

Ron Rice’s The Flower Thief (1962)

Initially admired for its apparent spontaneity, the film was actually shot – albeit mute – from a script in a studio, from which Leslie had banned Kerouac for inviting in Bowery hobos. (The role of a drunk falling asleep at the bishop’s feet was reassigned to the poet Gregory Corso.) Kerouac did subsequently get to improvise – drunkenly – the overdubbed narration. Still, it’s notable – as Barry Miles points out in his biography of Kerouac – that the home-movie stylings of the poets’ foolings around are in marked contrast to the classy nouvelle vague aesthetics of the close-ups of Delphine Seyrig (mysteriously credited as ‘Beltiane’), playing the fictionalised Carolyn in her first screen role. As the sole professional actor involved, she was the only one who’d take direction and give Frank time to compose his shots.

The tireless Mekas also supported and helped to promote the work of friends such as Ron Rice, who worked with the flamboyant gay performance artist and poet – and future Warhol ‘superstar’ – Taylor Mead. In 1960 New Yorker Rice shot the improvisational The Flower Thief – clearly influenced by Pull My Daisy – on a visit to San Francisco. It follows Mead frolicking around smoky North Beach cafes, fairgrounds and industrial wastelands while other beatniks enact a crucifixion. The critic P. Adams Sitney called the film “the purest expression of the Beat sensibility in cinema”, and certainly the combination of Mead’s carefree abandon and the film’s playful satirising of America’s sacred cows recalls Kerouac’s definition of Beat as beatitude.

London via Brighton: Communion

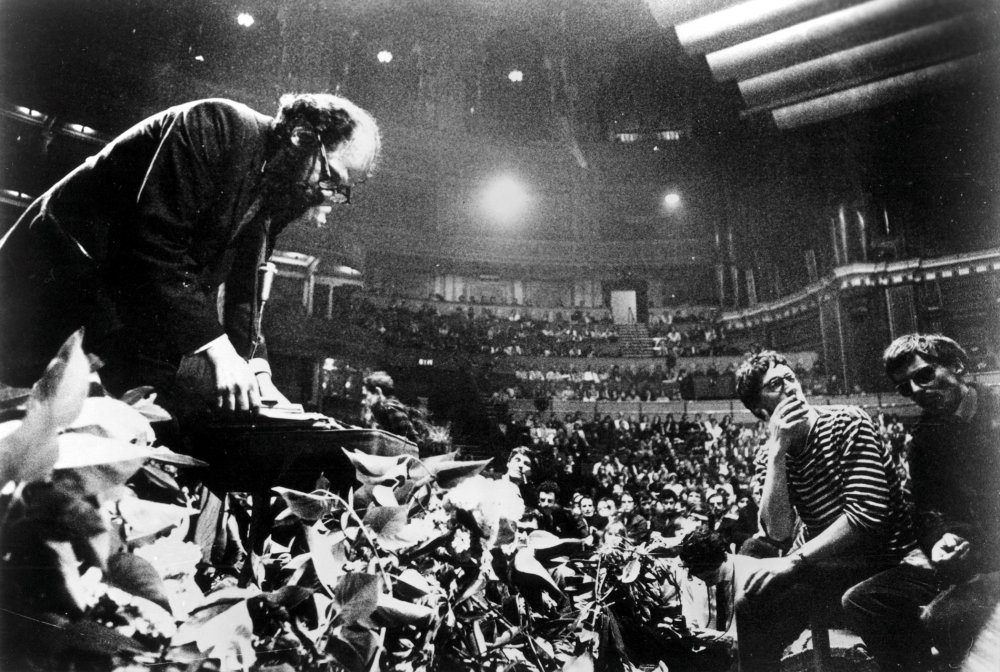

Allen Ginsberg on stage at the Royal Albert Hall in Peter Whitehead’s Wholly Communion (1965)

So – with the pollination of ideas across continents after the war – where were the British Beats? Strange to tell, in 1960 the most Beat scene in Britain (at least in filmmaking terms) wasn’t London or Liverpool, but Brighton – and based around one man.

Jeff Keen made his first film, Wail (1960), on 8mm. A woman is hounded by a motorcycle gang, and an astonishing rapid-fire collage of comic-book images of sex and violence ensue. In the end, by the sheer transformative power of spontaneous collage, the woman has been seduced and becomes one of the bikers herself, riding off into the sunset with them.

The film was made in the same year as Beat Girl, a British exploitation picture of beatnik rebellion – lensed by Broughton’s collaborator Lassally. While Beat Girl Jenny (Gillian Hills) learns the error of her rebellious ways, Keen’s girl loves the new thrill and hits the road with the bad boys.

Keen’s next trick was entitled Like the Time is Now (1961). Three beatniks, including Keen and his wife Jackie, hang out in a room, smoking, drinking from a jug of rotgut and listening to jazz records. Occasional animated speech-bubble captions appear, “Like the electricity’s melting, MAN!” Like Wail, it was shot mute, probably to be projected at Keen’s local film club over jazz records. It’s somewhat reminiscent of Brakhage’s Desistfilm – albeit with less angst and more madcap humour – though it’s unlikely Keen had seen the latter at the time.

William Burroughs in Conrad Rooks’ 1966 Chappaqua

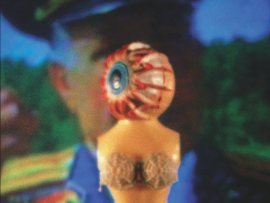

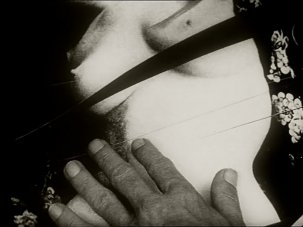

As the 60s progressed, London became a favourite destination for beats on their travels. In London, Burroughs made a handful of films with Antony Balch (who by day distributed sexploitation and horror movies) and Brion Gysin, deploying both the latter’s cut-up method of writing and his Dreamachine, a device for generating hallucinatory patterns by stroboscopic light.

In their aforementioned Towers Open Fire (1963), shadowy agents of a syndicate control the media through witchcraft. Burroughs dispenses various strategies for combating their mind-control, including literary deconstruction, drugs that counter opiate addiction and not least the Dreamachine. A commando raid on the syndicate ensues, and Burroughs reappears as a military radio operator commanding “Towers open fire!”. The syndicate members (one played by fellow junkie writer Alexander Trocchi) are obliterated. Evidently, for Burroughs and his coterie, cinema held a liberating promise of multimedia cultural subversion, of “storming the reality studio.”

By the mid 60s, Barry Miles’ Better Books shop on London’s Charing Cross Road had become the place for Beat poetry readings and underground film screenings. (In fact the performance poet Bob Cobbing and filmmaker Stephen Dwoskin founded the London Film-Maker’s Co-op there in 1966.) In May 1965 Ginsberg dropped by to read – and at the end of that evening, in a moment of wild ambition, it was decided to convene the International Poetry Incarnation, a mass gathering of Beats at the Albert Hall, the biggest venue in the city. The ensuing sell out marked the arrival of the hippie counterculture in Britain, and Peter Whitehead’s record of the event, Wholly Communion, remains perhaps the most important document of the profound influence the Beat Generation has exerted on British culture.

Legacy

Alex Gibney’s Magic Trip (2011)

As the social upheavals of the 60s unfurled, so many of the Beats were transformed or consumed by them. MacLaine was a casualty before they even happened. Brakhage made increasingly more abstract and ethereal films, seeking to document the visionary experience. James Broughton made The Bed in 1968, a sublime free-love pageant on the furniture on which humans spend the most part of their lives. Burroughs, Ginsberg and Orlovsky played parts in Conrad Rooks’ improvisational search for enlightenment and a cure for alcoholism in Chappaqua (1966), one of the few underground features of the 60s. Frank and Leslie both live on. Jonas Mekas still propounds a cinema that is made as human expression, free of the strictures of commercial pressure.

In 1964, while Rice was dying of pneumonia in Mexico, Neal Cassady, having divorced Carolyn, went on one final legendary road trip across America with writer Ken Kesey and his proto-hippie band of Merry Pranksters in a psychedelic painted bus whose destination sign read ‘Furthur’. They documented the trip with thousands of feet of 16mm film that, over the decades, lay dormant and grew legendary as the group disbanded – until finally Alex Gibney’s 2011 documentary Magic Trip allowed us a glimpse into that lost world, a world which in Beat terms perhaps marked the end of the road – and yet the birth of a new era.

Over the closing credits of Salles’s On the Road runs Super 8 footage of a man stumbling down a railway track, mumbling to himself while recordings of Kerouac reading from his work play on the soundtrack. Anyone familiar with the back story will recognise this faceless man as Neal Cassady, whose dead body was found on a railway track in 1968. His alcoholic soul brother Kerouac would follow him into that same dark tunnel the following year. While mainstream cinema continues to mine America’s mythistory, encasing it in amber, independently financed and free cinema that merely harnesses the Beat tradition continues to thrive. That’s another story, as is the remainder of Beat and underground cinema not covered in this excursion. It’s out there, just waiting for you to discover.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.