Last year, the focus of Cannes was on high heels. This time round we hope it stays on female-led cinema.

True, the stats are bad: only seven out of 49 films across the whole official selection are directed by women. But this year does offer films by female auteurs with singular visions: Andrea Arnold with her US-set road movie American Honey, and Maren Ade and her comedy-drama Toni Erdmann, both competing for the Palme d’Or alongside Nicole Garcia’s From the Land of the Moon (Mal de pierres), starring Marion Cotillard. Meanwhile Laura Poitras’s latest documentary Risk is one of the anticipated highlights of the parallel Directors’ Fortnight programme.

There are also exciting possibilities for discovery such as Delphine and Muriel Coulin’s The Stopover (Voir du Pays), their follow up to their pregnancy-pact drama 17 Girls, which focuses on two soldiers on brief leave from duty in Afghanistan. (One is played by Ariane Labed, who consistently stars in interesting films and who shone in Attenberg, Fidelio: Alice’s Odyssey and The Lobster.) Also featuring in the Un Certain Regard strand are the feature debuts of two female directors, Israeli Maha Haj – with Personal Affairs – and the French Stéphanie Di Giusto – with The Dancer. Directors’ Fortnight and Critics’ Week offer more first-timers too.

Directors may be godly in Cannes, but film is a collaborative art form, and if you look beyond the top line of the credits you’ll find many talented female filmmakers in the festival whose work is overlooked. How often do you see editors, scriptwriters, costume designers or DoPs heralded from Cannes? But their work and art is vital to the films on show.

Gathered here are ten women from across the spectrum of filmmaking, from under-appreciated and emerging directors to producers, editors, costume designers, scriptwriters and cinematographers. They all have films in the festival and they and their work deserve recognition.

Maren Ade

German director Maren Ade takes a magnifying glass to human relationships. The lives of her female protagonists are often disintegrating: her 2003 debut, The Forest for the Trees, charts the breakdown of a 27-year-old teacher struggling to adapt to her new city school; loneliness seeps out of every scene but there’s humour in there too. I don’t want to ruin its ending but let’s say it’s astonishing and brave for a debut that til then dealt in realism. A hit on the festival circuit, the film earned only a brief run at London’s ICA and has never gained a DVD release.

Ade’s second feature, Everyone Else (2009), about a holidaying couple’s deteriorating relationship, is an intense study of love and discord – and also delightfully unpredictable. Yet it met the same fate in the UK, despite winning the Silver Bear at the Berlinale Film Festival. Her films have won critical applause, but are frequently described as ‘small’. What’s small about human drama?

Ade’s everyday observational powers are out in force in her latest film, Toni Erdmann, about a woman whose father visits his business woman daughter out of the blue and decides she has lost her sense of humour. It’s Ade’s first film in Cannes, has received great reviews so far and is a leading contender for the Palme d’Or.

Ade doesn’t just direct – in 2000 she co-founded the production company Komplizenfilm with Janine Jackowski and has also worked as a producer on Miguel Gomes’s films, among others.

Marie-Hélène Dozo

A video interview with Roberto Minervini and Marie-Hélène Dozo discussing their work on his first film The Passage

In the realist dramas of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne – directors who favour long scenes shot in one take – Marie-Hélène Dozo’s work as their editor is often subtle. Think of the cuts colliding with the slamming doors in the opening scene in Rosetta and how they add to the ferocity of the scene, the restless pace of the film and, above all, the mania consuming its eponymous character. The Dardennes’ films have discordant rhythms which Dozo helps compose. They often open abruptly, Dozo and the brothers dumping us in the middle of a character’s everyday life; we are left to work out what’s going on. And, as with L’Enfant, they often end brutally too. Cutting away keeps sentimentality at bay and their character’s lives authentically incomplete and messy.

Dozo has worked with the Dardennes since their first fictional short Il court… il court le monde in 1987 and is part of the director’s regular collaborators (DP Alain Marcoen is another). The Dardennes view filmmaking refreshingly as a collective process: “Nobody is there to do just their job. They’re all really there for the same reason, which is to make characters come to life.”

Dozo has also edited Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s films (Dry Season, The Screaming Man), Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl and Roberto Minervini’s Stop the Pounding Heart and The Other Side.

Editing, as Mark Cousins has discussed, is an unsung art that has counted many women in its ranks throughout film history. Dozo is not the only female editor in competition at Cannes this year: The Salesman (Forushande) is cut by Hayedeh Safiyari, who regularly teams with Asghar Farhadi and who was responsible for the fast pace and tension in A Separation; Julie Monroe worked on Jeff Nichols’ Loving; and Marion Monnier edited Olivier Assayas’s Personal Shopper.

Esther García

Esther García in I’m So Excited (2013)

Esther García is Pedro Almodóvar’s right-hand woman, and one third of the most powerful triumvirate in Spanish independent cinema: the production company El Deseo, co-founded by Almodóvar and his brother and producer Augustín. García has managed Almodóvar’s shoots since the 1980s and has spent 30 years working with the notoriously demanding director: “Pedro knows exactly what he wants and it doesn’t matter what has to be done in order to obtain it,” she has said. He prefers continuous, sequential shooting which has huge financial and organisational implications, particularly in regard to locations. Garcia oversees this; ensuring they stick to their modest budgets is paramount to the survival of El Deseo and to the freedom of their filmmaking.

“It is hard to work for Pedro. But it’s very rewarding,” she told the New York Times in 2004. “My job is to get as close to Pedro’s vision as possible.” She thinks that producers have a creative role which is not very widely known. Alongside the Almodóvar brothers, she takes part in all the decision-making, but she’s also integral in picking other projects to fund. Just some of the films that Garcia has helped shepherd to screen with Spanish co-production deals include Lucrecia Martel’s The Holy Girl and The Headless Woman, Isabel Coixet’s My Life Without Me, Damian Szifron’s Wild Tales and Pablo Trapero’s The Clan.

She is also a force to be reckoned with one set: “I am able to interpret when Pedro’s ‘yes’ is actually a ‘no’. He is an incredibly respectful person, and at times when we are working, it is difficult for him to change things that have involved a lot of effort.”

Almodóvar’s fondness for his trusted production manager is evident on screen too: Garcia has cameos in Talk to Her, The Skin I Live In and I’m So Excited. In Broken Embraces the production manager in the film is even called Judith García.

Rebecca O’Brien

One of Rebecca O’Brien’s first jobs in the film business was finding the laundrette (and other locations) for My Beautiful Laundrette. She says she had no real concept of what producing involved then.

O’Brien first collaborated with Ken Loach 26 years ago, co-producing the political thriller Hidden Agenda, which won the Jury Prize in Cannes. Loach is surprisingly prolific for a director who makes films about challenging social and political issues: his latest, I, Daniel Blake, chronicles Britain’s job centres, benefit sanctions and food banks, seen through the eyes of the eponymous 59-year-old joiner who falls ill and becomes unable to work. That Loach directs so regularly is down to O’Brien, his regular producer since Land and Freedom and the co-founder, along with Loach and his regular writer Paul Laverty, of the production company Sixteen Films.

“From an early stage,” O’Brien tells me, “I discovered the co-production route because there is an audience in Europe for our films. Once you’ve done one film that way, it gets easier. But it’s never the same and some are more difficult than others.”

Building and maintaining these relationships is part of what she does (the fun bit of her job, she says), as is juggling lots of different financiers for each project. But she regards a producer’s job as so much more: “A lot of people think that a producer just puts the money together for a film, and that is not the case at all. The producer has an eye to the production right from the film’s inception to delivery, and beyond to the archive. You’re in charge of getting the film together throughout its life.”

She sees a producer as a sounding board: “There always many questions as you go along. As producer you’re the first second opinion. You’re the first audience at each stage. You’re in charge of the broad strokes of the film; you’re the one person who is constant with the director all the way through. The director is woking on the detail; I’m working on the overall strategy. But you’re also shaping the crew. You’re involved in casting. I get very involved in the marketing and I work closely with the distributors. During the shoot, you’re trouble-shooting any problems. You’re all over everything.”

Shahrbanoo Sadat

“I decided to make a film about my own experience in the village. A story about a community somewhere in Afghanistan from the perspective of a little girl who is an outsider and can’t see well.” These are the words of Shahrbanoo Sadat, one of the first female Afghan directors. She was just 20 and the youngest participant in Cannes Cinéfondation Residency in 2010 when she started to develop her feature debut Wolf and Sheep, which screens in the Directors’ Fortnight sidebar at the Cannes this year – and is one of most exciting prospects of the festival.

On her blog Sadat recounts her experiences growing up in rural central Afghanistan and how for seven years she couldn’t see because anyone with ‘eye sickness’ who wore glasses was believed to be blind. A girl with an Iranian accent like herself didn’t want to stand out anymore by wearing glasses.

Taking part in a French documentary film workshop in Kabul when she was 18 (and had started wearing glasses), she decided to track down an American eye doctor who came to her village and make a film about him. After he was killed by the Taliban she turned to fiction instead, setting up her own production company Wolf Pictures and making two shorts.

In her own words: “My vision is to explore how my people look at their lives, how they think and how they believe. I don’t want to show the dark or bright sides of Afghanistan because there are so many films like that already. I want to tell a story about how I see Afghanistan, about where I am living. I want to show the routine life in a village where people are totally disconnected from towns, from the city. They are busy with their farms and their flocks. The only danger are the wolves that can be seen and heard a lot these days.”

Sadat and her Danish German-born producer Katja Adomeit had wanted to shoot Wolf and Sheep in Afghanistan but due to deteriorating security conditions, and after delaying the production several times, they built an entire village in the middle of the mountains in neighbouring Tajikistan and shot there instead.

Natasha Braier

Argentinian cinematographer Natasha Braier started out on visually inventive low-budget Latin American indies like Claudia Llosa’s The Milk of Sorrow and Lucia Puenzo’s XXY. She was responsible for the monochrome hues of Shane Meadow’s Somers Town, and the freewheeling camerawork that captured the streets and passersby of Strasbourg in Jose Luis Guerín’s In the City of Sylvia. In David Michod’s The Rover, though, there was no room for serenity like in those films: she avoided the cinematographers’ paradise that is magic hour and shot the post-apocalyptic road movie on 35mm with an earthy palette that emphasised the dusty hell of the Australian desert.

She works with directors whose films display a love of visual storytelling and a desire to experiment with it (she has also shot shorts for Park Chan-wook and Lynne Ramsay).

It will be fascinating to see what she brings to The Neon Demon, Nicolas Winding Refn’s horror thriller about the LA fashion industry, and the first film of his to put female characters centre-stage. Early images from the film hint that it’s likely to be the most ravishing colour riot on the Croisette.

Braier spent two months finding the right set of anamorphic lenses, an old set called Crystal Express that no one uses anymore. “They’re great,” she says, “because they’re very soft and gentle and cosmetic on the faces. And I needed the skins to be as close to those [captured] on a fashion photo shoot.”

She is one of two female DPs with films in the main competition at Cannes (the other is Claire Mathon, who shot Alain Guiraudie’s Staying Vertical). Out of 64 features competing for prizes across the four competitions at the festival, only four films have female cinematographers.

Melissa Mathison

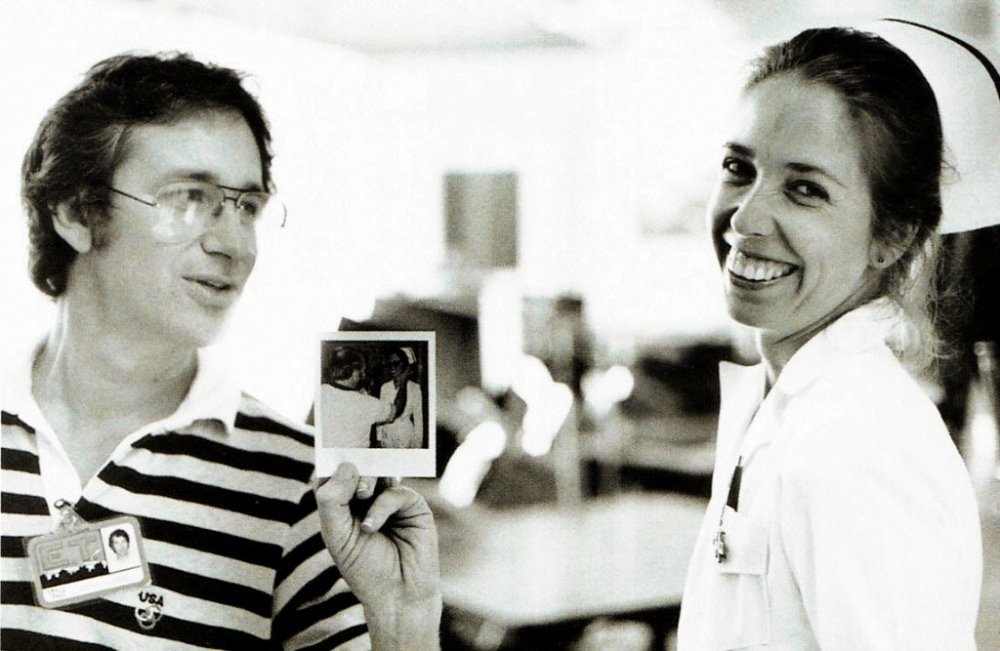

Melissa Mathison with Steven Spielberg making E.T. The Extra-terrestrial (1982)

Mark Rylance may have the title role in Stephen Spielberg’s The BFG, but the reason Roald Dahl’s book resonated with so many young readers is the way he filtered the world of giants and snozzcumbers through the eyes of the fearless and resourceful young orphan Sophie.

Dahl was great at portraying children. He wrote as if he still was one. Melissa Mathison, who died last year, had the same talent and it showed in her script for Spielberg’s E.T. The Extra-terrestrial (1982). Elliot, Gertie and their teenage brother Michael felt real. Her script never left their point of view or that of their crumpled-looking brown friend from outer space. Even E.T.’s glowing finger can be found in the script.

Mathison didn’t work that much after E.T. (she did write the script for Scorsese’s Kundun) but she collaborated with Spielberg one final time, adapting Dahl’s classic for the big screen. Many of Speilberg’s recent films (Bridge of Spies, War Horse, Munich) have left women in the background, and looking back over his career most of his films about children (from Empire of the Sun to Tintin) centre on boys. I look forward very much to seeing what Mathison brings to the story of Sophie and her adventures with another kind otherworldly being.

Ruth Negga

Ruth Negga in Jeff Nichols’s new competition title Loving

Since Ruth Negga’s breakthrough role as Kitten’s pregnant best friend Charlie in Neil Jordan’s Breakfast in Pluto (Jordan said she impressed him so much in casting he wrote the part for her), the Ethiopian-Irish actress has worked less in cinema, more in theatre and television, playing Shirley Bassey in a BBC2 film and starring regularly in the TV superhero saga Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. A small part in 12 Years a Slave and the title role of Scott Graham’s Iona marked her return to the movies, but it is her part in Jeff Nichols’ Loving that promises to propel her to many more prominent roles after ten years under Tinseltown’s radar.

Loving marks a departure for Nichols, whose Southern Gothic-tinged dramas have to this point focused on white men and boys. The film tells the true story of Mildred Loving (played by Negga) and her husband Richard (Joel Edgerton), who in 1958 defied the ban on interracial marriage in their home state of Virginia by wedding in Washington. Returning home, they were arrested and had to leave the state in order to avoid jail.

Nichols’s film charts their battle to overturn the legislation in the Supreme Court. “I was struck by the simplicity of the Loving’s story, and I hope to make this a painfully beautiful film,” he says.

Kirsten Johnson

Kirsten Johnson in her semi-self-portait Cameraperson (2016)

Kirsten Johnson has made documentaries all over the world. Some she has directed herself; but on many of them she is a DP for hire. Documentary cinematography does not get the attention that the visual crafting of fictional worlds does – but it should do. Johnson has talked about the freedom that she has enjoyed as a doc DP, how she always shoots shots for herself as well as recording what the director has stipulated. She has worked regularly with documentarian Laura Poitras and in a recent interview with Filmmaker magazine she revealed how Poitras had looked over her material and identified every single ‘off-piste’ personal shot she’d taken for herself and said “Do more shooting like this.”

With Poitras, Johnson has chronicled Iraq, Guantanamo Bay, American data centres and Edward Snowdon’s Hong Kong hotel room. For Citizenfour she shot the enigmatic, abstract traffic tunnel sequences that turned the ordinary into something strange and chilling. Their most recent collaboration is Risk, a portrait of Julian Assange, the founder of the whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks, which will be revealed in Cannes.

Johnson has even made a film about her experiences as a documentary cinematographer: Cameraperson won the jury prize in Sundance, is scheduled to show at Sheffield Doc/Fest in June and hopefully will come to cinemas across the UK after that. It’s an essay film comprised of unused footage she’s shot throughout her career and offers a singular insight into how documentaries are made.

On titling it Cameraperson she told Filmmaker magazine: “Any day I’m shooting, someone will accidentally call me a cameraman. That’s just the default name. People say, ‘What do you call yourself?’ I say, ‘I’m a cameraperson.’ That just feels to me like it says very clearly, ‘Anyone can do this.’”

Erin Benach

Erin Benach

Erin Benach has worked as a costume designer on two films in competition: Jeff Nichols’ 1960s set Loving and Nicolas Winding Refn’s horror-inflected ode to the fashion industry, The Neon Demon. While most designers largely regard their job as done if you don’t notice their work, Benach is known for being sartorially adventurous – the scorpion-adorned white satin jacket that Ryan Gosling wears throughout Drive being a case in point. Her work is a lot more intricate and time-intensive than you might think: Gosling’s jacket went through 15 or 20 versions before it was deemed perfect. Half Nelson was the first film she felt she put her mark on and she has worked regularly with Gosling since.

Benach is particularly good at creating worlds through costumes that feel timeless. After reading a script she always gathers together cult imagery for each character. Her designs demonstrate detailed thought about style and mood and how to subtly express personality and plot. “I have to picture how these characters will look, think about their style and every single nuance. It’s a very fun, creative process,” she explained to Time Out.

Working on Midnight Special with Nichols recently, she designed the utilitarian clothes worn by indoctrinated ex-cult members that signalled their inability and refusal to adapt to the world outside of the ranch. In the words of Nichols, who for his low-budget debut Shotgun Stories bought clothes from Walmart and drove over them until they were worn: “She’s on another frickin’ level”.

-

Cannes Film Festival 2016 – all our coverage

Browse all our coverage of the preeminent showcase of international and auteur cinema.

-

Women on Film – all our coverage

A window on our ongoing coverage of women’s cinema, from movies by or about women to reports and comment on the underrepresentation of women...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.