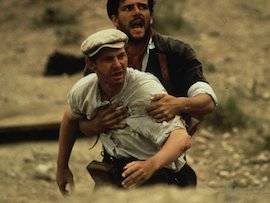

Half a century on from Cathy Come Home, and ten years after The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Ken Loach has made what is arguably his finest film since that Palme d’or-winner. While it’s certainly true that there are few surprises in Paul Laverty’s script – or indeed in Loach’s characteristically forthright direction – there is no denying either the utter relevance or the emotional power and political punch of the movie.

UK/France 2016

100 mins

Director Ken Loach

Cast

Dan Dave Johns

Katie Hayley Squires

Daisy Briana Shann

Dylan Dylan Phillip McKiernan

Even during the opening credit titles one feels in safe hands, as we simply hear the increasingly frustrated replies given by the titular Daniel (Dave Johns) to the largely irrelevant questions of a ‘health care professional’ assessing, with regard to an application for an Employment and Support Allowance, his ability to work after a recent heart attack. Though the 59-year-old Newcastle joiner has been advised by doctors and physiotherapists not to return to work for a while, and the woman interviewing him clearly has no proper medical knowledge, the tone at this stage is essentially comic: a sure indication of Loach and Laverty’s justified confidence in their knowledge of the film’s subject matter.

Indeed, as Daniel struggles with the almost Kafka-esque bureaucracy of modern Britain’s Department for Work and Pensions – endless waits on the phone, digital-by-default demands made even of those who’ve never once used a computer, patronising staff, unhelpful jargon, dark threats of sanctions – the movie simply focuses on the protagonist’s determined, even obstinate attempts to avoid poverty and potential homelessness while retaining his humanity intact: namely, self-respect, dignity and kindness to others. The last is most conspicuously evident in his encounter with a young single mother and her two children, new to Newcastle after two years in a cramped room in a London homeless hostel and likewise finding it almost impossible to make ends meet.

To reveal more of the narrative would be not only unfair but unnecessary. It’s not the plotting that counts here as much as the characterisation – deftly telling throughout, but blessed particularly by the performances of Johns and, as Katie, Hayley Squires – and the authentic quality of everything presented. Scenes in job centres and food banks ring terribly true; likewise but more positively, the pleasure Katie’s kids and Daniel take in each other’s company feels marvellously real. There may, perhaps, be some who’ll mutter ‘same old, same old’ upon encountering this enormously evocative slice of social realism, but there’s nothing wrong with artists sticking to what they do best; remember Ozu, Rohmer or Fassbinder.

That’s not, of course, to liken Loach’s work to theirs; simply to say that I, Daniel Blake is as timely today as was Kes in the late 60s or Raining Stones in the 90s. At one point, a minor character rails against Iains and Etonians, a forceful reminder that it’s not just the bureaucrats at the other end of a phone line or on the other side of a desk who are responsible for the demonisation and diminishing resources of the unemployed, poor and disabled; still more powerful, and just as pertinent, is a final appeal speech, Daniel’s simple but eloquent words indicating that none of us are mere clients, customers, scroungers or identity numbers but human individuals and citizens with rights, including the right to respect. If that’s been said before, there’s no harm in its being repeated, especially as eloquently and elegantly as Loach and Laverty say it here.

-

Cannes Film Festival 2016 – all our coverage

Browse all our coverage of the preeminent showcase of international and auteur cinema.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.