Web exclusive

The Man Whose Mind Exploded

The Man Whose Mind Exploded

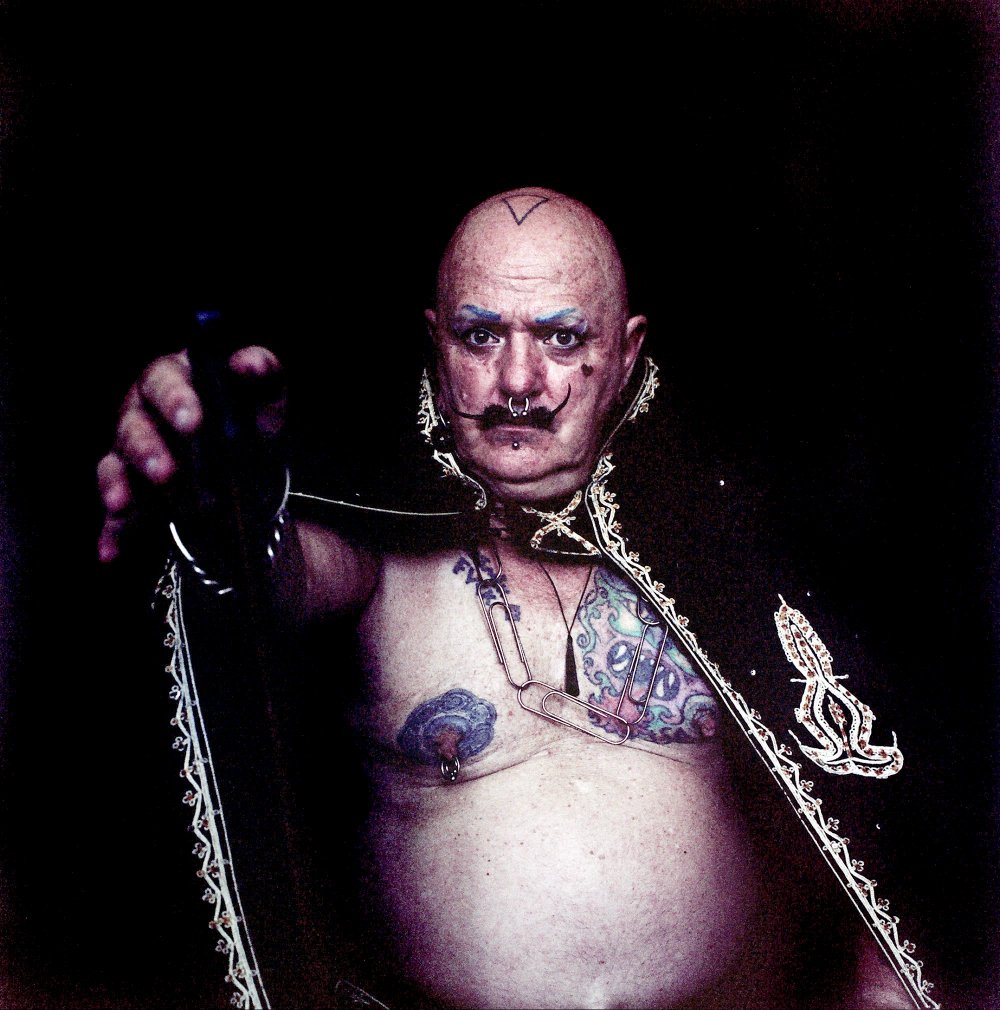

Ritualistically coating his moustache with black paint, his glittering eyebrows the electric blue of Kenneth Anger’s Shiva in Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, Drako Zahazar abides by the motto inscribed upon his arm to combat his anterograde amnesia: “Trust Absolute Unconditional.”

|

Director: Toby Amies |

Drako, 76, is a relic of British avant-garde royalty. A star of Jarman and Warhol films, he cuts a striking figure in his cape amid the council housing of Brighton. Slipping in and out of French and sharing stories of modelling for Salvador Dali with old people in bus shelters, he’s unable to create new memories. He inhabits a brilliant existential chaos, a reality that’s proving hard to sustain with his deteriorating health.

The handheld camera is frustrating, but perhaps necessary for the intimacy, as the film evolves from curiosity into responsibility. Scoping the dilemmas faced by Drako’s loving family, Amies strives to protect Drako’s unique world. His habitat is a grievous biohazard, as Drako adamantly protects his museum of memories and decayed foliage (“the plant is supposed to be dead”).

His relationship with Amies – or “Toby Jug”, as the director identifies himself on Drako’s intercom – is explored with transparency and humour. They make an eccentric pair; their well-spoken banter concerning the extraordinary collection of penis imagery adorning Drako’s flat is incredibly funny, as are Drako’s droll responses to Toby’s questions, delivered with unyielding conviction. Drako is fully aware of Toby’s gaze, and revels in it. The former spectacular life model and flamboyant nudist has transformed his council flat into the temple of his cluttered fantasies – and to navigate the Memento-like shrine of his pleasure dome is, as Drako declares, to “love it all”.

Sophie Brown

|

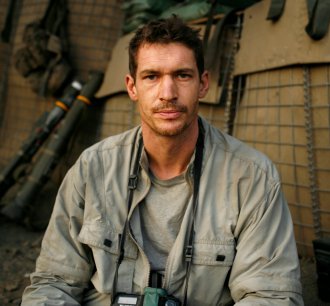

Which Way is the Front Line from Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington Director: Sebastian Junger |

+ Which Way is the Front Line From Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington

Directed by the late war photographer’s co-director on Restrepo, this film penetrates the murky allure of war and its roots in human nature. Hetherington’s attraction to the front line and instinctive ability to connect with his subjects was a catalyst for an incredible body of work that illuminates an engaging humanity among the destruction. At the heart of the story is the photographer’s fascination with how men see themselves in war, and why, which makes this a compelling exploration of self-perception and the imagined space of violent action to compare with Joshua Oppenheimer’s Jury Award winner The Act of Killing.

Sophie Brown

Chimeras

Chimeras

The teasing question of whether or not Chinese contemporary art can escape the suffocating tendrils of globalisation and, specifically, Western influence, is central to Mattila’s elegantly shot, drily amusing dual character study.

| Director: Mika Mattila Finland 2013 [homepage] |

We’re first introduced to young photographer Liu Gang, a working-class student making waves at the prestigious Beijing School of Arts. His sly, John Stezaker-esque collage work is concerned with skewering China’s ongoing cultural colonisation by the West, even if he himself seems defeated by it (“My generation has grown up in the globalised world. It’s impossible to resist it”).

Seemingly bearing out his prematurely jaundiced worldview is his counterpart in the film: leonine fiftysomething Wang Guangyi, founder of the trailblazing avant-garde North Art Group in the 1980s and now one of the world’s wealthiest artists. Secreted in a modernist palace of riches, Wang cuts a palpably uncomfortable figure, struggling to reconcile his current moneyed status with his radical revolutionary past.

Over and above finding such richly compelling figures upon which to focus, Mattila’s masterstroke is not to force comparisons between the two men. Instead, though intelligent, theme-driven editing, he opens up space for the viewer to draw their own connections and process the fount of cultural and historical information dispensed and discussed by Gang and Guangyi in sensitively captured private moments. (An unobtrusive, restrained presence, Mattila has snagged tremendous access to his subjects.)

Alison Klayman’s 2012 film Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, while enjoyable, never dug particularly deep into the core sociopolitical issues underpinning Chinese contemporary art; thankfully, Chimeras fills in the yawning gaps created by Weiwei’s gigantic personality.

Ashley Clark

|

The Great Hip Hop Hoax Director: Jeanie Finlay

UK 2013 [homepage] |

+ The Great Hip Hop Hoax

A perceptive dual character study accounted for another of my Sheffield picks. Finlay’s warm-hearted and consistently surprising documentary tracks the fortunes of two Scottish rappers circa 2004 who, tired of being ignored on account of their ‘unfashionable’ ethnicity, meticulously developed a cover image as fun-loving Californians and saw their fortunes – rapidly, unbelievably – change. It would be wrong to divulge too much information here (the less one knows beforehand the better), but it’s a funny and moving study of friendship and identity laced with a subtly astringent take on the music industry and its myriad vagaries.

Ashley Clark

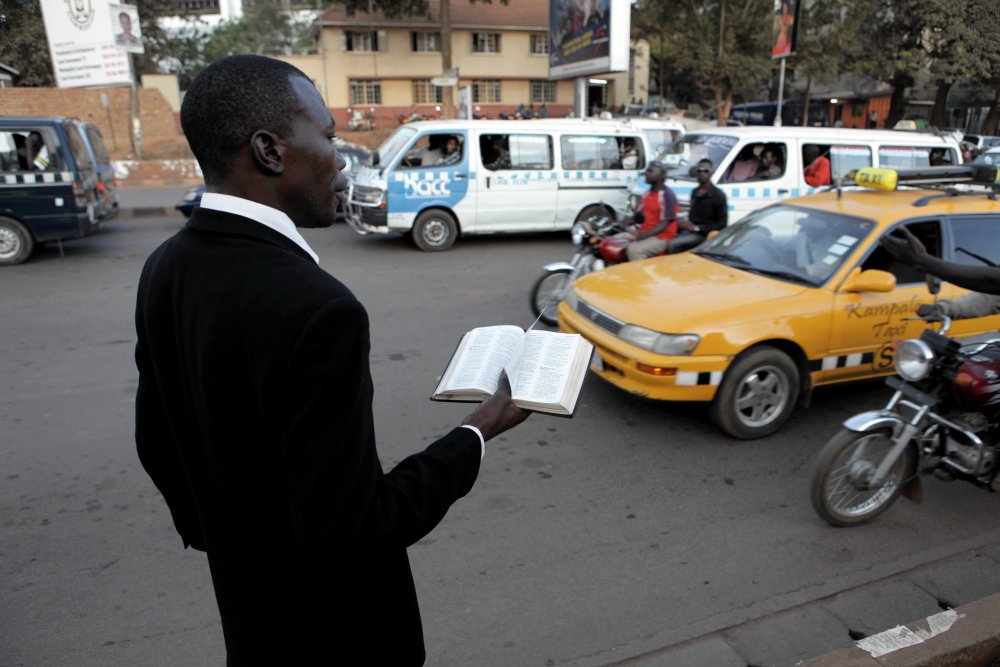

God Loves Uganda

God Loves Uganda

| Director: Roger Ross Williams US 2013 [homepage] |

Winner of the Sheffield Doc/Fest Youth Jury award, God Loves Uganda is a disquieting look at contemporary colonialism’s influence on the notorious Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Bill. It follows US-based Christian enclave IHOP (the International House of Prayer) as their young missionaries voyage to Uganda to preach the word of God (and right-wing radicalism), led by charismatic pastor-stroke-prophet Lou Engle. Williams documents the spread of IHOP’s crusade against homosexuality and sexual freedom in unsettling detail: from the condemnation of condoms as Uganda’s AIDS rates skyrocket to the murder of hate-crime victim and LGBT activist David Kato (and picketing of his funeral), the film makes clear the brutality of IHOP’s imported religious diatribe.

Yet Williams also finds dark comedy in IHOP’s audacious displays of religious fervour and entitled imperialist attitudes, always managing to walk a line between condemnation and wry, journalistic observation. The film gives IHOP the screen time to defend their choices, depicting them with tact and humanity. A rational counterpoint is offered in the form of tolerant Ugandan Bishop Christopher Senyonjo – but it’s the scenes of the idiosyncratic missionaries that are the most illuminating, both satirical and bitingly, frighteningly real.

Simran Hans

|

Muscle Shoals Director: Greg Camalier |

+ Muscle Shoals

With a soundtrack featuring Aretha Franklin, Etta James, The Rolling Stones and Wilson Pickett, Camalier’s energetic portrait of the legendary titular Alabama recording studio is hard to imagine as anything but a crowd-pleaser, though its depiction of wearied producer Rick Hall and his personal adversities adds colour. Growing up in abject poverty, abandoned by his mother and witness to the tragic deaths of both his brother and father, he’s healed by “the songs that came out of the mud”, his own story contributing to the region’s rich mythology.

Tinged with the spiritual magic of the neighbouring Tennessee river, Muscle Shoals is a soulful portrait of Hall’s journey out of the swamp and into the studio.

Simran Hans