Web exclusive

The End of the Line (2007). Are our documentaries doomed?

1. Campaigning pains

Looking back at the 2009 edition of the festival formerly known as the Sheffield International Documentary Film Festival (these days abridged for the Twitter age), it’s hard not to want to start by dispensing with the contretemps at its most over-subscribed panel session. Lighting on one of the year’s big documentary trends – the rise in advocacy-driven, ‘social justice’ documentaries (think The Age of Stupid), often ‘filmanthropically’ supported by campaigning charities (The Vanishing of the Bees by the Co-operative, The Cove by the Oceanic Preservation Society, The End of the Line by a host of NGOs from Greenpeace on down – the festival convened a panel to debate the subject Campaigning Documentaries: The Thin Line Between Passion and Propaganda. And to light the touch-paper, it invited Moral Maze contrarian Claire Fox as arbiter.

Question: is it worse for an oil company than a charity to fund a film? “If Dr. Goebbels were to turn up with a huge sack of money he’d have documentary filmmakers queuing up,” argued BBC Storyville’s Nick Fraser, cautioning us that “some money is better than other money.” (Goebbels did of course have documentary filmmakers queuing up; and there are plenty of denialists of everything from climate change to the HIV-AIDS link who have broadcasters and film festivals today feeding from their hand. The real question is whether or not the money is compromising editorial independence, or the art. Some filmmakers have made great works with oil-company backing.)

The idea of partnering charities and documentary filmmakers has lately been championed by the Channel 4 Britdoc Foundation, with its Goodfilm.org dating site and Good Pitch funding forums. The foundation’s chief executive Jess Search found herself in one corner of the panel, as it were. Working with charities, she argued, Britdoc and its filmmakers had been on a learning curve they’d never have experienced if they’d been funded by broadcast television. Charities were less jaded than TV people; they could bring films to new audiences, use them in different ways and give them a longer life-span. And they understood impact and change. Don’t all documentary filmmakers want to make a difference?

Debate: 'Campaigning Documentaries: The Thin Line Between Passion and Propaganda'

The other side of the table then read out the charge sheet. Writer and filmmaker Kevin Toolis was worried about the strings that came with charity money. “NGOs like Greenpeace are as mendacious and self-centred and unaccountable as the CIA,” he posited, adding that they were “politically unexaminable, push their own sectarian agenda” and are “human and just as corrupt”. Plus they have no editorial standards or understanding. The upshot: the documentaries they fund don’t look at “difficult, controversial subjects” but are “aimed at a wide consumer audience, dealing with what we all regard as intrinsic good”; they pander to majority opinions and confirm rather than challenge prejudices. Where “old-fashioned investigative journalism reveals something about the world” and comes with the ambition of critical engagement and being fair to the other side, campaigning documentaries constitute a “shrill back-and-forth” that merely targets attitudes.

Fox herself wondered if Search’s new breed of docs were “simplistic messaging and advocacy that says it’s serious investigative documentary”, suggested that “what we’re really interested in is feeling good about ourselves”, and asked the audience to vote on whether campaigning docs amounted to “charity advertorials”.

“We’re demeaning humanity and contributing to the idea of politics not being important,” added Fox’s old Living Marxism comrade, now anti-environmental ‘equality campaigner’ Ceri Dingle. “It’s a shame Jess doesn’t recognise how status quo her films are,” she continued. “Don’t kid yourself that because they’re popular, moralistic and ‘doing good’ that they’re changing things in any way. That’s the tragedy and anti-politics.” Some of Search’s slate might be “fantastic”, she allowed, but they weren’t going to change society until they dug “for the truth”.

(The audience also learnt that propaganda wasn’t what it used to be: “Propaganda to me used to mean the propagation of many ideas to the few – as opposed to agitation, the single idea to the many,” she garbled. “Today it’s a dirty word… flung at things you don’t agree with,” a use she immediately demonstrated by explaining that whereas others considered The Great Global Warming Swindle propaganda, she instead considered The Age of Stupid (or in words, “Plane Stupid”) propaganda. What had happened to the good old propagandists’ aspiration to “take people beyond what they spontaneously know and think, beyond their immediate experience to challenge prevailing views”?)

Nick Fraser, Jess Search, Claire Fox, Kevin Toolis and Ceri Dingle

Fraser attempted to raise the level of erudition by quoting Saul Bellow and Flaubert, but largely sat out the fisticuffs, except to adduce Eugene Jarecki’s Why We Fight and the output of Boston’s WGBH as evidence that documentaries can be both balanced and polemical. But if the debate was truthfully about the travails of investigative journalism, perhaps the finger should be pointed less at charities than at broadcasters’ dereliction of their remit to support that work. “Times are so fucking bad that instead of quarrelling over the definitions of campaigning journalism… we should be devising some means of stopping Channel 4 and BBC from selling the past and destroying what in this country is a pretty remarkable tradition,” he sallied, branding their abdication from the funding landscape “a major act of cultural vandalism.” Search had set out her stall with a similar blast: “I don’t recognise a world in which TV commissioning editors are solely concerned with truth and art and want to give filmmakers independence to go off and tell stories as they see them,” she argued.

It took the floor to provide what little light was shed on charities’ likely effect on editorial independence. One filmmaker explained that the only difference between NGO and broadcast funders is that “you can’t change your mind halfway through a film for the former.” A delegate from Human Rights Watch vouched for that group’s self-searching staff and internal discussions, while repeating Search’s point that films can instigate “critical, revelatory debates” in a way that written reports rarely can. Such films “are never a complete statement”, of course, so HRW’s own film festival makes a point of following its film showcases with live debates about the issues raised. But like propaganda, apparently, the quality of such debates can sadly vary wildly.

2. Wear your film with pride

RiP! A Remix Manifesto

Toolis and Dingle at least weren’t wrong about the dullness of self-righteous, hectoring documentaries, particularly when they tell you what you already know. (The problem was that nobody on the panel was naming the films they were talking about.) I’d been looking forward to seeing Brett Gaylor’s RiP! A Remix Manifesto, a treatise on digital mashup culture and the perils of maximalist copyright laws, ever since signing up to be pelted with Facebook messages about its screenings around the world.

Not that Gaylor’s free-culture arguments are wrong, but the film is all too stymied by his belief that he’s right; he bandies the word ‘freedom’ around as wantonly as George W. Bush, and scoops an interview with Marybeth Peters, head of the US Copyright Office, only to cut her out of the film as soon as she’s demonstrated that she’s a techno-fuddy-duddy on the wrong side of the fence. (She’s the past, see, and The Past Tries To Control The Future, a point the film drums away at ad nauseam.) You almost expect to hear that if you’re not with the film-maker then you’re against him. Gaylor also makes a tactical mistake chewing off great chunks of his hero Lawrence Lessig’s Powerpoint lectures on the injustices of modern-day copyright law: Lessig’s orations are some leagues more lucid and level-headed than Gaylor’s breathless peroration. Still, it’s nice that Gaylor got to make pals with his other hero, mashup maestro Girl Talk. And for the uninitiated, the film does give a useful account of recent milestones in remix culture.

Erasing David

I’d also had high hopes of David Bond’s Erasing David since seeing it pitched at the 2008 Britdoc festival; a sort of documentary 39 Steps, it would apparently endeavour to dramatise the extent of our surveillance state by following the director’s attempts to hide himself from the same. The trouble, of course, was that the film didn’t actually have access to the tools of the state (I’ve seen the Bourne movies; I know what we’ve paid for), so the hide-and-seek seemed jarringly DIY. Various concerned talking heads were interspersed with beside-the-point musings on whether David’s flight was a sign of paranoia, or immaturity.

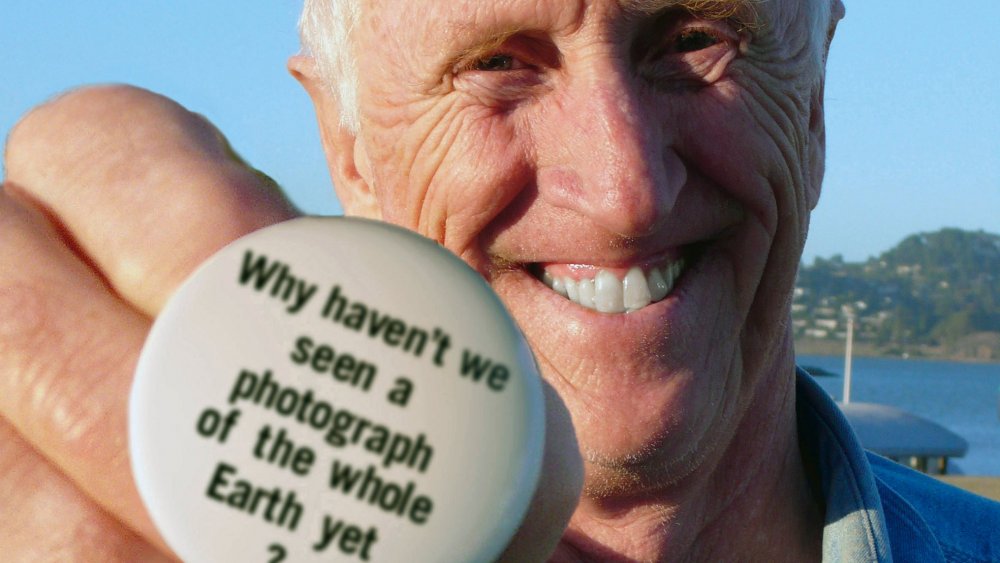

Earth Days

Better was Robert Stone’s Earth Days, an extremely (occasionally too) stylish history of the burgeoning environmental movement in the U.S. through the 1950s and 60s, up until the first Earth Day in 1970. It starts with a damning montage of each American President since Eisenhower warning in turn of the urgent need to rethink the country’s unsustainable development trajectory, then tracks back through its richly illustrated account of joined-up American dissent with testimony from many of the story’s movers and shakers (Steward Brand, Paul Ehrlich, Denis Hayes, Stephanie Mills, Stewart Udall and more). The film screeches to a halt with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, and his symbolic removal of Jimmy Carter’s solar-energy panels from the roof of the White House.

Shelter in Place

These days in deepest Bush country – Port Arthur, south Texas – oil and gas refineries now release suspiciously regular, legally sanctioned ‘upsets’ of toxic chemicals into the local environment. No surprise that the people trapped in closest range to these leaks are largely poor and black, nor that the effects of the pollution on this populace has not been scrupulously monitored. Official advice is that they ‘shelter in place’: stay indoors. Photojournalist Zed Nelson’s Shelter in Place never fulminates, but shoots the scene beautifully, gets to know its oppressed characters (there’s a wonderful scene in which one battered old man takes brief heart from the news of Obama’s election) and puts the powerful on the spot, though sadly only in the figurative sense. (Full disclosure: the film’s producer Hannah Patterson is a friend, so I would say that.)

3. Character observations

Moving to Mars

Of the festival’s character-based, observational docs, Mat Whitecross’s Moving to Mars: A Million Miles from Burma was a cute choice for Sheffield’s opening-night film, since it follows two Karen families (one headed by a civil engineer, one by an illiterate farmer, less propitiously) from their refugee camp over the Burmese border in Thailand to Sheffield’s grey ‘city of sanctuary’, where they settle in neighbouring semis and slowly acclimatise to their new isolate urban individualism. The film was sleekly photographed and scrupulous; you just wished its patience had been rewarded with a little more acuity.

Men of the City

Mark Isaacs was more serendipitous with the shooting of his Men of the City, filming its odd quartet of City of London workers (a divorced, workaholic hedge-fund trader, a weary, chain-smoking insurance broker, an immigrant-Bangladeshi sandwich-board man and a philosophical street-sweeper) as the credit-crash broke around them. Perhaps there was less cultural distance between film-maker and subjects, but Isaacs also seemed better able to get to the hearts of his characters. In fact you felt he was most alert to what he abhorred about the world he depicted – the all-consuming mercilessness of London’s free-market human traffic. Only the street sweeper had found a way to maintain his moral equilibrium and the sense that he was contributing his work to a community.

Rough Aunties

For picking up a society’s broken pieces, though, few can be as indefatigable as the subjects of Kim Longinotto’s Sundance Grand Jury prize co-winner Rough Aunties. A mixed-race group of women in Durban, South Africa, who staff a volunteer support group for sexually abused children called Bobbi Bear, they swing from grim tragedy to ongoing calamity (a horrific roll-call of otherwise unheeded abuse cases and deaths) with amazing fortitude and not a little gallows humour. Longinotto filmed them for a mere ten weeks, but she captures the extent of their dedication and depth of their solidarity against a horrendous backdrop: a portrait of humanity at its best and worst.

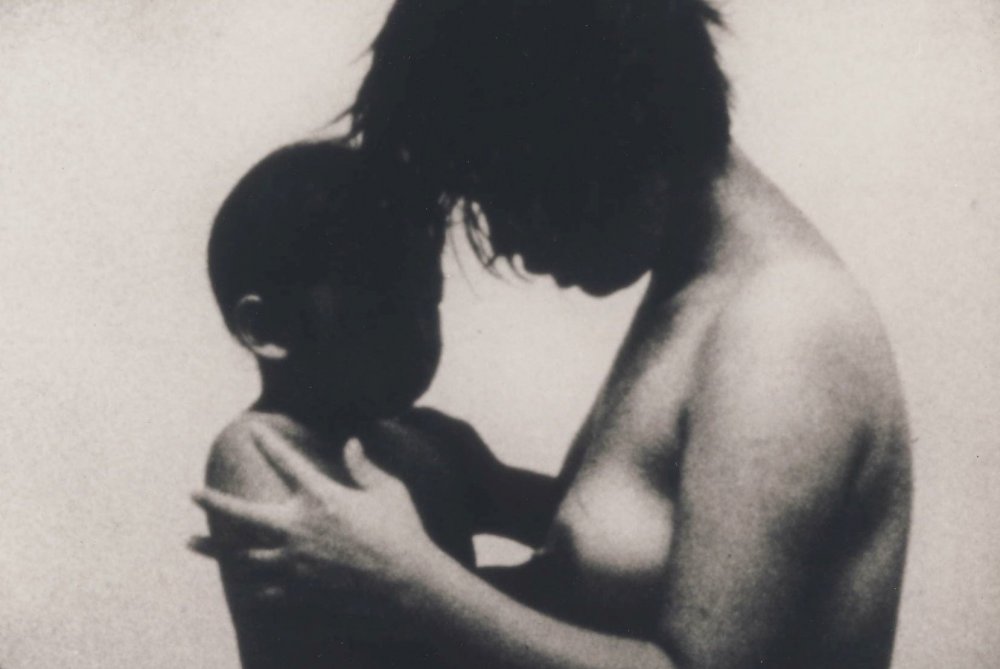

Katatsumori (1994)

Intrepid women were also a theme of the third of Mark Cousins’ Doc/Fest retrospectives of the ‘golden age’ of Japanese documentaries (the 1960s and ’70s, natch), following 2007’s Noriaki Tsuchimoto programme and last year’s selection of Ogawa Shinsuke’s works. This year’s focus turned those two directors’ epic social-portrait observations on their head, focusing on the subjective selves in front of (and behind) the camera. I missed Imamura Shohei’s Madame Onboro (1970), alas, but Naomi (The Mourning Forest) Kawase’s ‘granny collection’ – Katasumori (1994), See Heaven (1995), The Setting Sun (1996) and Birth/Mother (2006) – were unsettlingly intimist, interventionist depictions of Kawase’s relationship with her ‘grandmother’ Uno (in fact her grandfather’s older sister, who adopted her after her parents’ divorce).

It’s a relationship that spans memories of Uno’s late husband, Naomi’s childhood, Uno’s ageing process and Naomi’s own procreation (Birth/Mother, most remarkably, starts with an unstinting perusal of Uno’s naked, pocked body in the bath, and ends with movingly silent footage of Naomi giving birth), and seems to be conducted entirely through the camera, whose unblimped motor is a frequent refrain on the soundtrack. The films aren’t so much ‘observational’ as ravenous for connections and contact; there’s little context, no wide or establishing shots, just long, leading close-ups, reaching out like Naomi’s occasionally visible hand.

Extreme Private Eros (1974)

Hara Kazuo’s even more intimate, ill-advised but bizarrely valiant Extreme Private Eros (1974) tries to be fly-on-the-wall, but given that the various walls are those of his headstrong ex-wife Miyuki, who has taken their son with her in search of new lovers, the uncertainty principle is writ particularly large here. “The only way to keep the relationship was to make a film,” muses the director at the beginning of the film, although there clearly wasn’t much chance for Miyuki’s next relationship, with a bar hostess, what with her ex hovering with a camera over their every exchange.

She goes slumming in Okinawa, pamphlets the local bar girls and gets Hara beaten up by gangsters, fails to adopt a mixed-race Okinawan baby, but gets pregnant by a black American G.I. and gives birth on camera, proudly unassisted. She also midwives for Hara’s sound girl Sachiko, whom he has got pregnant off-camera, and starts up a baby commune. What does Rei, their son, make of all this? Miyuki wants to raise him as “an aggressive fighter”, but alas, she laments, he’s the image of his dad, with Hara’s cowardliness and disposition to become “hysterical around her. He’s so mean…”

It’s true that we see Hara weeping extravagantly at Miyuki’s assertion that she loves her G.I.; later, filming her giving birth, he’s too nervous to fix the focus, though he keeps on filming. After the screening Hara told the audience he saw himself as the film’s main character. The film was a piece of defiant self-expression in which he knew he had to show his weakness; younger self-documenting Japanese directors by contrast seem to be asking for help. (The film closed on Miyuki dancing topless at a nightclub. Those were the 1970s…)

Winnebago Man

Ben Steinbauer mounted a search of a different kind in Winnebago Man, titled after the “angriest man in the world”, Jack Rebney, unwitting star of a ’90s cult video featuring foul-mouthed outtakes from a series of industrial videos Rebney had recorded working his way around a Winnebago luxury trailer. (You can see the clip reel on the film’s website.) The film was at its most fascinating offering a potted history of viral videos (and their cruelties) before and during the YouTube age. Rebney himself, a former TV journalist, turned out to be hiding with failing eyesight up a mountain in northern California; despite a strong, ongoing sense that the film was about to run out of material, Steinbauer managed to ride with Rebney to a sweet rapprochement with his unsolicited and somewhat humiliating celebrity.

4. Music docs, and the award-winners that got away

Pianomania

Unsurprisingly, given the marketplace, Doc/Fest was almost as strong in music documentaries as in green-themed films. It even brought in Israeli conductor Itay Talgam to present his ‘legendary’ masterclass Music as Multilayered Storytelling, in which clips of diverse conducting personalities from Ricardo Muti to Richard Strauss to Leonard Bernstein were adduced to probe the ambiguities of (more or less) collaborative authorship. Exactly whose story were they telling? It was a question that underpinned many of the more interesting documentaries in the festival.

I caught two of the music docs. The more polished, appropriately enough – Robert Cibis and Lilian Franck’s PianoMania – was the fruit of a year spent in the company of Steinway Vienna’s top piano tuner, Stefan Knupfer, as he sources the right instruments for various different-minded grand pianists and prepares for Pierre Laurent-Aimard’s new Bach recordings. Unlike the slightly incredulous sound engineers at the recording, Knupfer is an analogue man, ready to deploy scalpels, glue or tennis balls to get the sounds his clients want, and he makes you hear it, too. It made for an ear-opening portrait of genial, slightly eccentric perfectionism.

Taqwacore: The Birth of Punk Islam

Form also followed function in Omar Majeed’s Taqwacore: The Birth of Punk Islam, a comparatively ragged portrait of America’s proto-Muslim-punk-rock scene. You could play it in a double-bill with last year’s Heavy Metal in Baghdad (S&S October 2008), sure, but the film was both looser and richer – and a little less gobsmacked.

Whose story was it telling? Partly that of the various Islamic punks who have taken up guitars against a world that stereotypes them; partly that of their erstwhile prophet, the white rebel Islamic convert Michael Muhammad Knight, whose 2003 book The Taqwacores anticipated just such a movement before it existed. He follows them on a road tour of the American north-east states (culminating in a bust-up at the bland Islamic Conference of America, whose organisers take exception to the tour’s only female performers: “‘Islamically appropriate’ means no women singers”)

Later some of the acts travel to Lahore, play a couple of rooftop gigs and smoke cheap pot while Knight goes chasing memories at a nearby super-mosque, and takes class issue with the conservative euphemisms (‘good families’; ‘bad values’) of middle-class Pakistanis. Pulling itself different ways, the film was a little shapeless, but a pretty sharp yell.

After all this, the punchline to my own festival visit was that I hadn’t managed to see a single one of the award winners. (Thankfully at least the Innovation Award winner, Patrick Bergeron’s dizzying split-screen travelling montage Loop Loop, is up online.) It certainly sounds like I missed out on Erik Gambini’s Special Jury Award winner Videocracy; then again, the final tally of audience favourites seems to bear out that this was a particularly diverse collection of movies, with little sense of groundswell or convergent tastes. And that may be the way the movies are moving. Here’s to an even more varied 2010.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.