Web exclusive

Harun Farocki’s New Product (2013)

“The truth of art lies in its power to break the monopoly of established reality to define what is real.”

— Herbert Marcuse

The coarsened grammar of documentary filmmaking is everywhere these days, co-opted by what creative industrialists call ‘factual entertainment’ or ‘unscripted content’. From cooking shows to reality TV, cruel talent shows to surveillance cameras, nagging images of the ‘real’ contaminate our perception of reality. What used to differentiate documentary from fiction was a determinable link with the historical world, a connection with a social and physical dimension that existed independently of the camera.

|

24 October-3 November 2013 | Lisbon, Portugal |

Today reality is staged and propped-up for the camera. Every aspect of daily life, no matter how trivial, is instantly recorded, posted online and exhibited. Against the digital neorealism of social networks, Doclisboa’s films reaffirmed the necessity to understand our predicament critically and act accordingly. We are never only spectators but also actors, especially when leaving the cinema: this seemed to be the festival’s implicit suggestion.

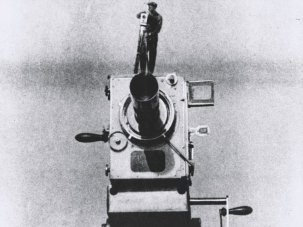

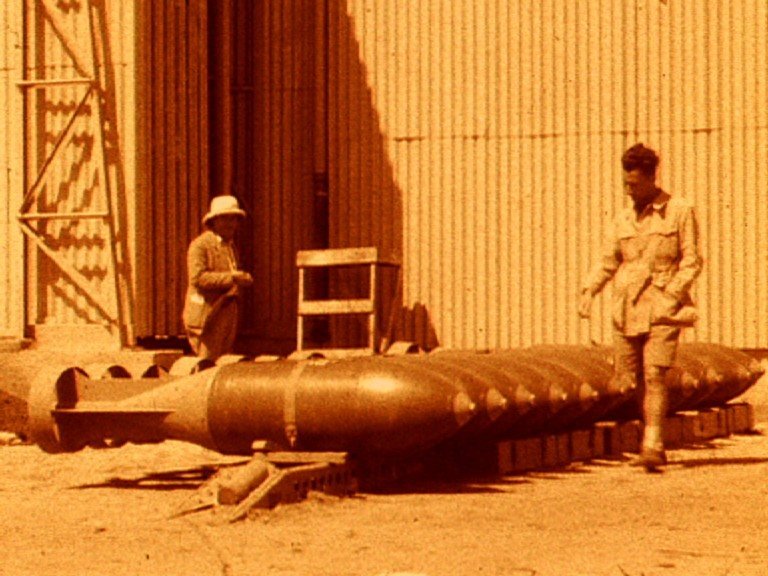

By way of its opening film, the sponsor-unfriendly Pays Barbare (Barbaric Land) by Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi – a half-convincing attempt to show the contemporary relevance of archive footage of Italy’s fascist colonial past – the festival expressed its determination not to surrender to the blackmail of austerity. Since culture is deemed irrelevant and unprofitable by the ruling neoliberal oligarchies, they might as well be reminded of how priceless it ultimately is. The scarcity of funds was met by an abundance of ideas, films and curatorial trajectories.

Pays Barbare (2013)

Though traversed by many sections, sidebars and collateral events, the festival’s underlying strand was epitomised by its stated aim: to think and to act (for apathy is always violent). The hybrid nature of most films felt more like a necessity than a stylistic choice. Fiction as the projected desire and will to create alternative realities, with documentary realism reminding us of our departure point: this seemed to be artistic vocation of the most cogent films seen in Lisbon.

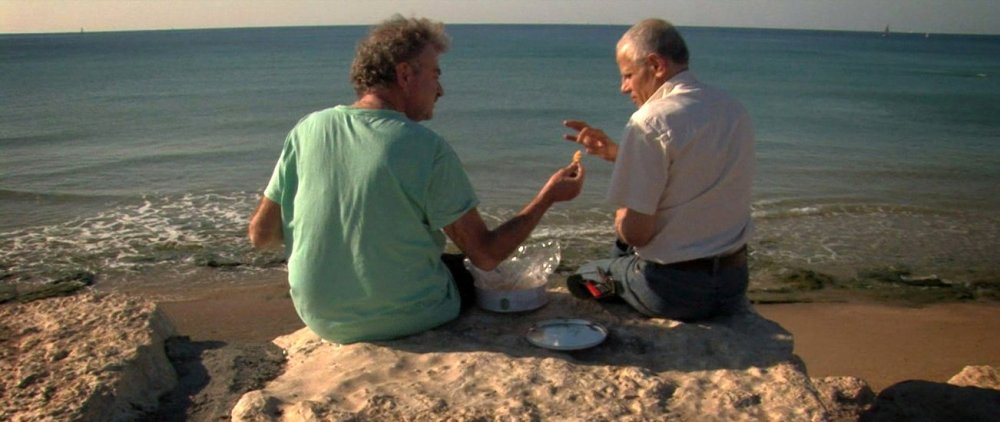

One film that exemplified without oversimplifying this tendency was Avi Mograbi’s Once I Entered a Garden, which received a special jury award. The (Israeli) director and an (Arab) friend of his set out to make a film about a bygone Middle East where Arabs and Jews lived in peace with each other (while Jews were having a much harsher time in the Christian world…)

Once I Entered a Garden (2013)

Their fictional project, whose potential feasibility outside the frame is testified by their heartfelt friendship, never comes into being, for their imagined garden is confronted by a sadly real one – a garden where, according to a Hebrew sign, “foreigners are not allowed”. If only the author of that sign had read Israeli historian Shlomo Sand’s books regarding the invented and paradoxical nature of Zionist purism… Disarmingly simple, Mograbi’s latest film manages to unearth the tragic and complex contradictions of modern Israel, whose colonial nature and supremacist drift prevent utopian imagination overcoming sectarian reality, in film as well as in reality.

Another friendship was the subject of another awarded film, Blood (which won a Special Mention) – that between Giovanni Senzani, a former leader of the leftwing paramilitary organisation the Red Brigades, and the film’s director Pippo Delbono. This was a study of a different country, Italy, similarly shaken in its recent past by what the state has labelled ‘terrorism’ but which had all the connotations of a low-intensity civil war.

Reflected and refracted through the story of their friendship, which Delbono obsessively documented over the past few years, and the personal losses they both experience during the course of the film, we see the history of a country and two different generations facing their respective failures. Eloquent are the scenes where the director and Senzani are in a car, having lost their way, looking for directions, both oblivious of the way they are going.

Blood (2013)

Amongst other, nuanced things, Blood is an intimate film about loss and defeat whose repercussions are not confined to its protagonist but involve a whole country – its unresolved past and its dark present mirrored in the final images of L’Aquila, a ghost town in the heart of Italy. It’s a country that neither Senzani’s generation, with its Marxist fervour, nor Delbono’s one with its Buddhist withdrawal have saved from ruination.

The festival winner, Joaquim Pinto’s essay film What Now? Remind Me [also the Special Jury Prize winner at the Locarno Film Festival – see S&S October 2013], narrates its director’s struggle with AIDS and hepatitis as he agrees to undergo an experimental medical treatment. Faced with the ultimate personal affliction – one’s own illness – Pinto transcends himself and conveys the richness of a lifetime spent working and loving, breathing and recording. His voice is choral; the stories it carries and recounts are collective, almost selfless. His flux of consciousness is anything but solipsistic; his lifespan matches, meets and interacts with the world he continued to inhabit passionately despite his disease.

What Now? Remind Me (2013)

From intimate musings on the fragile finitude of his own livelihood measured against illness to the timely reminder of when Germany was relieved of its debts in 1954 to facilitate its economic recovery, the film makes no distinction between the personal and the historical, the public and the private. What Now? Remind Me is an extremely brave film that doesn’t shy away from the imperfection of life and is unafraid of bearing the signs of said imperfection onto the very matter of the film itself.

It’s symptomatic that the one film that didn’t feature a personal story was Harun Farocki’s latest New Product, a faithful and frightening recording of a corporate meeting where the company’s new headquarter/business park is being discussed.

New Product (2013)

While talk of ‘a brighter future’ and collective wellbeing has completely disappeared from alternative discourses, these once leftist concepts resurface at this board meeting. Here the executives of a big corporation discuss their employees’ happiness as yet another factor to be taken into account in order to maximise profit. In Farocki’s film we get disturbingly close to the friendly face of modern capitalism where affectivity as well as labour time is what is being extracted from workers. No longer based on overt exploitation, contemporary corporatism hides itself behind the satisfaction of our desires.

It’s precisely in this respect that films – with their utopian (un)realism – can become accomplices in the reclaiming of our life and happiness from the ingratiating tyranny of profit. Because to think and act in today’s situation is not some romantic or idealistic vagary, but an urgent necessity.