Web exclusive

As the Flames Rose (O que arde cura)

This year’s edition of IndieLisboa was a pressure cooker. With southern Europe on the verge of tumbling into an economic and political abyss, the escalating situation that prompted the festival to take action – political only in a theoretical, Cahiers-like sense – was the Portuguese government’s decision to impose 100 per cent cuts in public funding on all cinema projects.

Emotions ran high, brought into focus by two events: first, a multitudinous congregation of cinephiles and filmmakers gathered together outdoors for the projection of a protest piece, beautifully woven together for the occasion, comprising the best sequences in Portuguese cinema history, from Aniki Bóbó (1932, Manoel de Oliveira) to Tabú (2012, Miguel Gomes). Then, the death aged 76 of one of the giants of Portuguese cinema, Fernando Lopes, who together with Glauber Rocha co-founded the Novo Cinema Portuguese. IndieLisboa and the Portuguese Cinematheque together improvised an homage to Lopes, the centrepiece a screening of his mythical Belarmino (1964).

Portugal has been in the cinematic vanguard for decades; a nation that regularly produces the greatest number of filmic rarities on the planet – currently, only the Philippines is as defiant and free in its screen fictions – and accumulates historical figures of almost biblical status. The Old Testament founding prophets (some still alive and working) such as de Oliveira, Paulo Rocha, Manuel Mozos, Pedro Costa and Joao César Monteiro rub shoulders with the younger New Testament filmmakers – Miguel Gomes, Gabriel Abrantes, João Pedro Rodrigues, João Nicolau, Sandro Aguilar – who keep their legacy alive. Furthermore, the Museum Calouste Gulbenkian and the Portuguese Cinematheque were both curated by an apostle of Henri Langlois, João-Bénard da Costa (aka Duarte de Almeida when he was acting in de Oliveira’s films), the educator of and inspiration to a whole generation of Portuguese audiences and filmmakers.

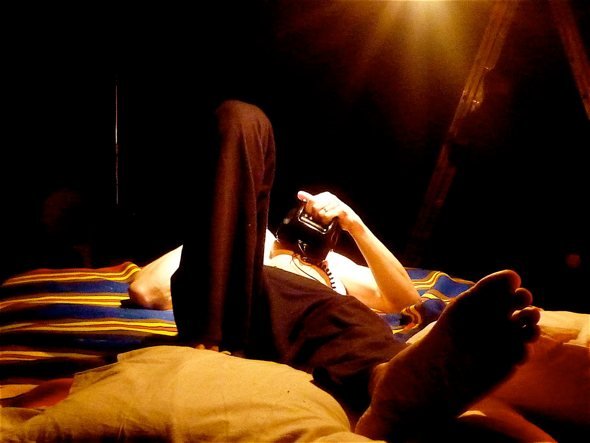

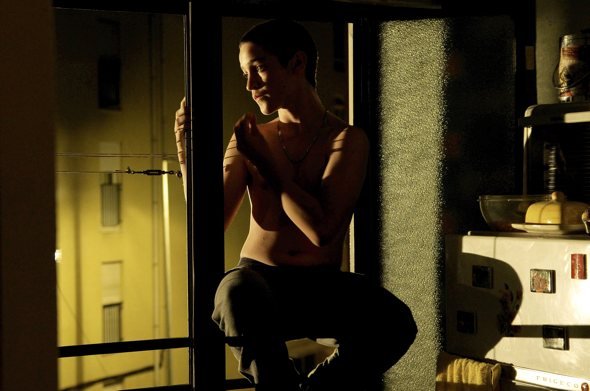

For Portuguese cinema, a budgetary tabula rasa would represent a terrible interruption of this brilliant stream of consciousness. The best homegrown film in IndieLisboa was in fact a short, which takes place during the fire that burned down an area of Lisbon in 1988. O que arde cura (As The Flames Rose), directed by João Rui Guerra da Mata, is based on Cocteau’s play The Human Voice, in which a man breaks up with his girlfriend over the phone. The man is played by the filmmaker Rodrigues, a powerful screen presence possessed of a disturbing physicality. There is not a single take that is not visually inventive and vibrant, theatricalised with strategies inherited from Hans-Jürgen Syberberg and Fassbinder, the camera lingering lovingly on the forsaken man’s body.

Rafa

It transpired that in Portugal right now the media is focusing not so much on Miguel Gomes (although Tabú is doing wonderfully at the box office) as on a young filmmaker called João Salaviza [Vimeo account], who won the Palme d’Or in Cannes for his short film Arena, to accompany the Golden Bear he won in Berlin for another short, Rafa. Salaviza is precisely the kind of injection of youth that Portugal and the film industry in general need. Less formally ambitious that his compatriots, more ‘social’ and easier to assimilate, Salaviza prowls the streets with his camera like an armed urban guerrilla (how not to think of the Dardennes?), but without imposing a strong style (as per Pedro Costa). His first feature is eagerly anticipated.

At IndieLisboa he showed twin works – Rafa and the really short Cerro Negro. Their protagonists are boys whose parents are in prison; their strongest trait is the freshness and spontaneity that the non-professional actors display in front of the camera. Let’s hope he resists the siren call of the big festivals, and instead manages to carve out enough space and time to develop those residues of Pasolinian emotion in his work.

Neighbouring Sounds (O som ao redor)

From Portugal we turn to Brazil, where talented young directors are also fortunate to work contemporaneously with old masters. The career of Kleber Mendonça Filho [Vimeo account] seems parallel to that of Miguel Gomes – a very active film critic who didn’t make his first feature until he was 40 years old. Neighbouring Sounds (O som ao redor; webpage) is a choral film set in a middle-class neighbourhood in Arrecife that doesn’t seem to owe anything to anyone, even if at times it brings to mind Paul Thomas Anderson. The way it’s edited leaves its characters incredibly exposed, defenceless even, at the end of sequences. O som is not perfect, but it has the urgency we were expecting from Brazil post-Lula, showing us the state of things but leaving spaces for the viewer to draw connections and try to understand.

Rua Aperana 52, the new film by 66-year-old Brazilian maestro Júlio Bressane, takes its title from the street where he grew up in Rio de Janeiro. The film is a veritable flood of memories of a life lived in the city, its charged editing establishing links impossible to explain without a blackboard. Rua Aperana 52 mixes boleros with images from Bressane’s own films (standing in for his memories), all shot in the street of the title with Sugarloaf Mountain looming in the background. It’s a massive film, worth the whole programme of any festival, even one as enterprising and tenacious as IndieLisboa.

Translated by Mar Diestro-Dópido.