With a couple of days to go to its end the Cannes festival ought to be feeling proud but punchy from the plaudits and the buffeting it’s had. Spike Lee wore Love and Hate jewellery on his fists and the mid-festival combination of his rapturously received BlacKkKlansman (a cert for one of the prizes) and Lars von Trier’s divisively gruelling The House that Jack Built had more than a few heads spinning.

Festival de Cannes 2018 runs 8–19 May.

Lee’s film is a hugely enjoyable lampooning of Tarantino’s style that parallels White Supremacist and Black Power movements in 1970s Colorado Springs through the eyes of John Stallworth (John David Washington), the county’s first black cop. The Afro-ed, Shaft-styled officer is soon assigned to an undercover unit where he figures out how to infiltrate the KKK using just a telephone and his partner Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) – this unlikelihood is apparently based on a real case. Cartoonishly raucous though many of the scenes are, they are gracefully played – the racists are just complex enough in their madness and stupidity; the Black activists stay true to the cause. If the humour sounds too cosy for the subject matter, don’t be fooled. This film has many stings, not least in its absolutely flooring tail.

The House that Jack Built (2018)

Blackkklansman shines in contrast to von Trier’s tiresomely provocative auto-analysing serial killer portrait, brilliantly put together though it is. Matt Dillon (good in a treadmill of a role) tracks us through five major ‘incidents’ from his murderous life – some of which are unwatchably vile – which he regards pompously as a kind of art form. Despite clips of Glen Gould playing Bach and constant references to architecture and literature in a voice-over interview of Jack conducted by the unseen ‘Verge’, the film becomes as boringly OCD as Jack himself. Nothing could be more exhausted than the von Trier seam of ironic black comedy is right now.

Cannes buffetings have come because it hasn’t quite been able to shake having been one of the scenes of Harvey Weinstein’s alleged assaults. How else to explain the lack of the advertising hoardings that usually clog the Croisette or the rumour that hotel bookings are substantially down this year?

The Netflix dispute, about which I’ve already written in our June 2018 issue, adds more grist to this mill. The protest of 82 women led by Jury president Cate Blanchett against the lack of female directors selected for the Cannes festival throughout its history was only partially effective since it so clearly stuck to Cannes’ dress code – though Kristen Stewart took her heels off later in the week to walk up barefoot without censure. All these details add up to a watershed feeling about this year, yet the change that was most touted to be disastrous, the delaying of press screenings until the morning after the Competition premieres, turned out to be workable.

Everybody Knows (2018)

Luckily good films have been plentiful. As soon as Asghar Farhadi’s weak opener Everybody Knows was out of the way (see my review linked below) the Competition got off to a strong start and has sustained a high level with my picks for likely prizes being Alice Rohrwacher’s Lazzaro Felice, Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War, the aforementioned Spike Lee joint and Koreeda Hirokazu’s Shoplifters, though there’s still six films yet to be seen.

Happy as Lazzaro (Lazzaro Felici, 2018)

I’m not usually fond of tales about holy fools but Rohrwacher’s ragged twist on a folktale Happy as Lazzaro makes an inventive, beguiling mystery out of a sharecropper exploitation scandal. At Inviolata, an island estate seemingly frozen in the 1930s, Lazzaro (Adriano Tardiolo), a simpleton, is in thrall to his arrogant young flip-phone wielding master Tancredi (Luca Chikovani), who himself is in his own rebellion with his aristocratic family. An accident to Lazzaro somehow brings the present into focus and, after finding Inviolata deserted, the recovered saint-like boy sets out to bring the destroyed servant community back together again.

Shoplifters (Manbiki Kazoku, 2018)

Kore-eda’s Shoplifters takes on another unstable community, an outlaw family adept at petty crime and crammed into the grandmother’s apartment, the father figure of which, Osamu Shibata (Franky Lily), rescues and adopts a scarred and battered four-year-old girl from abusive parents, who then joins Osamu’s son Shota (Jyo Kairi) on thieving trips to the shops. Like several of kore-eda’s other films, Shoplifters has the feel a true crime story, but this subtle, tender family portrait is much better scripted, structured and performed, and is happily less pristine, than the directors films have been of late.

Cold War (Zimna Wojna, 2018)

Thrilling in gorgeous b&w, Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War portrays a whirlwind, border-hopping amour fou between Wiktor (Tomasz Kot), a reticent pianist-composer and Zula (Joanna Kulig), a vital singer-performer. For more detail read my review below but let me reiterate that Kulig is astonishing in her role, a Jeanne Moreau de nos jours.

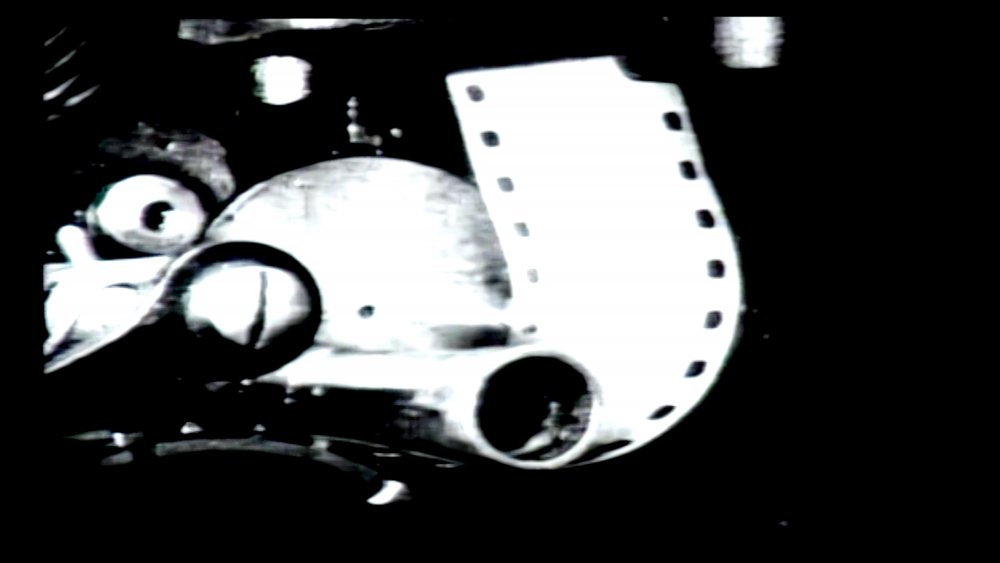

The Image Book (Le Livre d’image, 2018)

Among the most pleasing bits of trivia at Cannes has been to see a latter-day Jean-Luc Godard film leading the Screen Daily star-rating chart for the Competition (to which I contribute). Like all of Godard’s recent films Image Book makes you want to see it again before daring to comment, but I will say that Godard’s usual gnomic pronouncements have a Prospero edge to them this time, as if he knows this might be his last work. He carries on with all the usual manipulation/destruction of images and apt quotations of written texts but his rhythm now seems comfortably similar to a series of memes.

3 Faces (2018)

One dud for me in the Competition was Jafar Panahi’s Three Faces, in which Marziyeh (Marziyeh Rezael), a young aspiring actress from Turkish-speaking rural Iran, emotionally blackmails actress Behnaz Jafari by sending her a scary cellphone video. This brings Jafari and director Jafar Panahi to Marziyeh’s village by car. The ensuing road movie has many nice touches, many of which can be seen as either tributes to or borrowings from Kiarostami. What I find most off-putting is the vein of self-aggrandisement that runs through the film, of the director as a quiet god signalling his virtue.

Under the Silver Lake (2018)

A more extreme disappointment was Under the Silver Lake from David Robert Mitchell, the director of the 2014 indie hit It Follows. Andrew Garfield plays Sam, a jobless inconsistently interested peeping tom who gets embroiled in a Lynchian conspiracy theory/graphic novelistic noir plot set in present day Los Angeles. Tonally all over the place and clumsily put together, the film, though beautiful at times, further alienates through its relentlessly misogynistic view of the women he meets who are all on display for his sexual delectation. Asked to do so much angsting about nothing but increasingly desperate plot twists, Garfield isn’t up to the task.

- Check back soon for a review of Under the Silver Lake.

Sorry Angel (Plaire, aimer et courir vite, 2018)

I was very taken by Christophe Honoré’s 1993 Paris-set portrait of gay loves Sorry Angel, which others have found a little too much (it was the only film at any screening I’ve attended, other than von Trier’s, that has elicited a small flurry of boos). The film, which centres on the lifestyle of HIV-positive playwright Jacques (Pierre Deladonchamps) and his affair with Breton student Arthur (Vincent Lacoste), evokes a wonderful mood of time, place and romantic memory and is a work of high craft and deep feeling. I would be surprised but delighted if it wins something.

Ash is Purest White (Jiang hu er nv, 2018)

An outsider for the prizes, Jia Zhangke’s elegant slow-burn portrait of love, self-sacrifice and disillusionment Ash Is Purest White follows the affair between Qiao (Zhao Tao), a gambling den hostess, and small-time gangster Bin (Liao Fen) that leads Qiao to prison. The film is deep in inference and it had me wondering whether shame/loss of face or sheer disinterest motivates Bin in rejecting her. I still don’t know.

At War (2018)

In great contrast to this calm film was Stéphane Brizé’s At War. Workers at an auto parts factory in the South of France discover they are going to be shut down despite being told two years earlier that no such decision would be made for five years. Vincent Lindon plays the bullish union rep who encourages a strike that spreads to other factories owned by the same firm.

The first hour consisting of Lindon haranguing his bosses to make the same point over and over again is not exactly high cinema but Brizé alleviates the repetition and relentless anger by treating the film as if it were a music video, the score keeping up the tension and pressure more pleasantly. But the film only really takes off in the real negotiation scenes between the unions and the German car manufacturer bosses of the industrial group. Authenticity here clamours with painful truths about the way things are, many of which got rounds of applause from the audience. There’s a shock ending, though, that feels more sensational than it need be.

- Check back soon for a review of At War.

Girl (2018)

I’ll finish this round-up with the two best films from the Un Certain Regard section. Huge applause greeted the end of Lukas Dhont’s Girl, in which trans teenager Lara (Victor Polster), on the path to her new body, wants also to be a ballerina. It’s impeccably done, and danced and acted with conviction and grace, though it also treads water at times.

A Long Day ’s Journey into Night (Di qiu zui hou de ye wan, 2018)

And lastly there’s Bi Gan’s A Long Day’s Journey into Night, a labyrinthine noir-inspired dream logic film that would be easy to dismiss as all style, especially when you’re given 3D glasses and told to use them only at the moment the protagonist puts them on, after which the final 50 minutes of the film is all in one drifting highly accomplished take. With a noir narrative of murder and betrayal and a quest that seems to take Luo Hongwa (Jue Huang) into mines and permanent darkness, this was among the most beguiling films I saw here even if it was hard to figure out on one viewing what it was all about.

- Check back soon for a review of A Long Day’s Journey into Night.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.