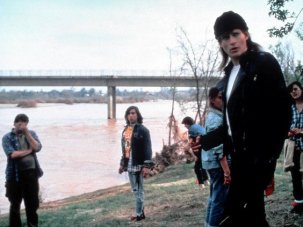

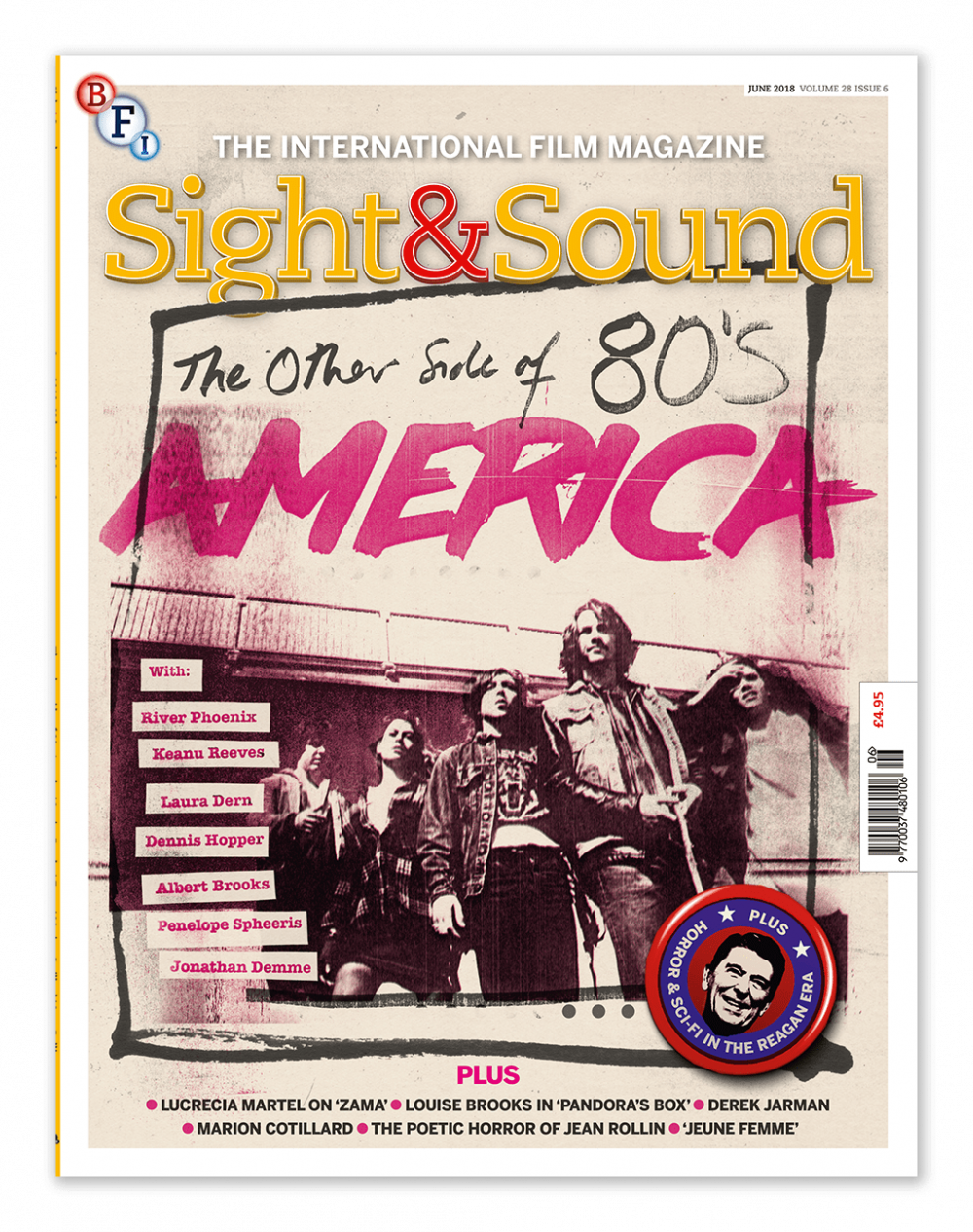

This month’s cover feature is also the Deep Focus special, transporting the reader back to the Other Side of 80s America – namely, those often overlooked films and directors that turned their back on the high-concept spectacle and cartoonish action film, the flag-waving and corporate swagger, preferring to operate in a low-key, personal register more reminiscent of the character-driven films of 70s New Hollywood and to focus their attention on marginal lives at the sharp end of Reaganonics. Dennis Hopper, Penelope Spheeris, Alan Rudolph, Joyce Chopra, Bill Sherwood, Joan Micklin Silver and Albert Brooks are just a few of the names to conjure with in this anti-pantheon, all profoundly committed to the oblique angle, the real thing, the downbeat tone.

Posted to subscribers and available digitally 30 April

→ Buy a print edition

→ Access the digital edition

→

On UK newsstands 3 May

Nick Pinkerton’s article points to the 80s as a watershed in American culture, before the internet blurred subcultural distinctions and ‘indie’ became big business. “The 80s seem like the last moment when the mainstream-counterculture dynamic that had acted to define postwar American culture offered a clearly comprehensible narrative and counter-narrative. Hair metal or college rock? Multiplex or cult cinema? What side are you on?”

Pretty much all of the characters in these films regard mainstream life as something to be escaped at all costs, a burden to cast off, they feel ill at ease in their time. This was never more true than for young people, whose bleak prospects in this era can be ascertained by the post-shoot body count on Martin Bell’s documentary about homeless youths Streetwise (1984). And it was largely down to the alternative cinema that Pinkerton explores to convey the devastation wrought by the spread of HIV/Aids in this era.

Anne Billson’s supporting article develops the thesis in the direction of subversive low-budget genre fare “unburdened by notions of good taste” – think Brian Yuzna’s Society (1989), James M. Muro’s Street Trash (1987), and of course the maestro himself, Larry Cohen, in films such as Q: The Winged Serpent (1982) and The Stuff (1985).

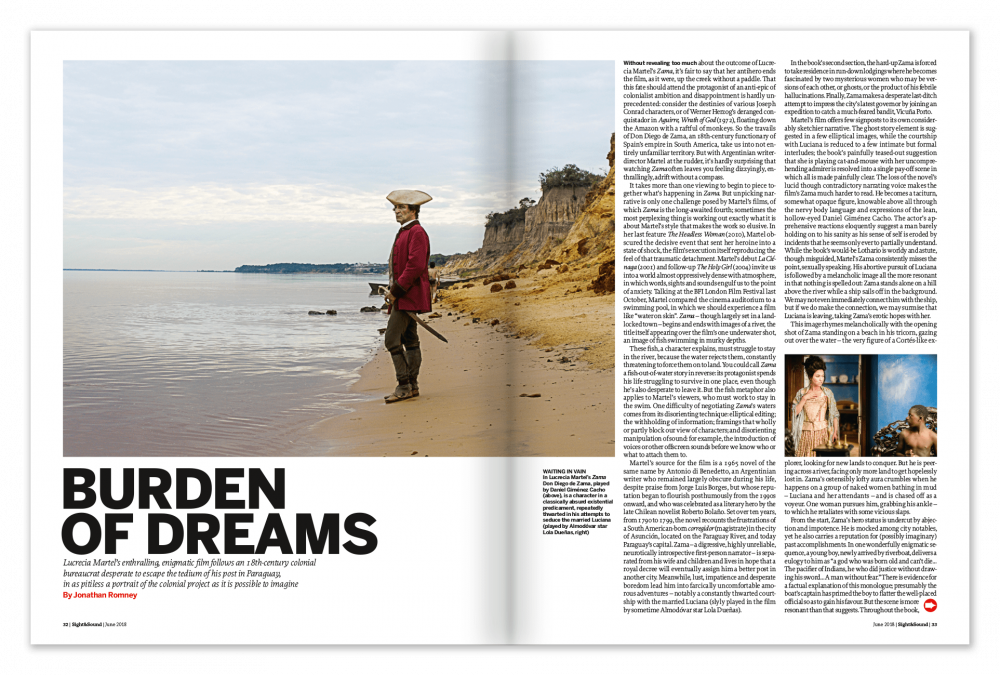

Zama is the long awaited new feature from Argentinian Lucrecia Martel, an anti-epic of frustrated colonialist ambition which many critics have argued is her greatest film to date. Zama is adapted from a 1965 novel by Antonio di Benedetto and follows an 18th-century colonial bureaucrat desperate to escape the brilliantly evoked tedium of his post in Paraguay. In Martel’s version of this story, as Jonathan Romney explains, the titular Zama “becomes much harder to read. He becomes a taciturn, somewhat opaque figure, knowable above all through the nervy body language and expressions of the lean, hollow-eyed Daniel Giménez Cacho.”

As usual with Martel, the psychological vicissitudes of her characters are expressed through disorienting technique – ellipsis, withheld information, partial views and manipulation of sound. It makes for, as Romney says, ‘tantalisingly murky waters’. In an interview with our editor Nick James, Martel says that for her, “a film is not telling a story, it is an artefact or representation of a way of perceiving things which aims to challenge one’s own way of perceiving the world, so as to upset things, like an earthquake.” Prepare to be rocked and shaken.

The Other Side of 80s America: watch our trailer for the June 2018 issue

Marion Cotillard is, of all the famous French actresses one can think of, the only one to become a truly transnational star, claims our expert Ginette Vincendeau, owing to the sheer range of work she has under her belt, including domestic comedies, Hollywood blockbusters, American independents, music videos and films by respected European auteurs, such as her latest, Arnaud Desplechin’s Ismael’s Ghosts. She also won an Oscar for her role as Edith Piaf in La Vie en Rose, the film that turned her into a global celebrity.

So what’s the secret of her success? According to Vincendeau, “her agency as an actress is evident from the consistency of her performance style across different genres, roles and languages… her acting is characterised by understated features and naturalistic mannerisms designed to project subtle emotions. Her persona is primarily melancholy, bittersweet.” So one of the great stars of the modern age, and as one journalist put it to Cotillard, “You are a French exception all to yourself.”

To celebrate the re-release of GW Pabst’s Pandora’s Box and a new BFI Classic book on the film by Pamela Hutchinson, we look back at the female characters in the silent and early sound films of the Austrian director, who was fascinated by female psychology. As Hutchinson reveals, “His women are rebellious, sexual, intelligent and often outrageous, but always credible and intriguing instead of mere types. In Pandora’s Box, for example, the sexual monster of Wedekind’s plays is reconfigured as a human, sweetly innocent character.”

Perhaps Pabst was reflecting his moment, the rise of the new woman in 1920s Weimar, who formed the majority of the cinema-going audience. His vision, not of a future equality but of vengeful goddesses creating a sexual tyranny, was sadly disrupted and thrown into reverse by the rise of the Nazis in the early 30s. But let’s be grateful for this run of amazing films before the cataclysm.

Our Home Cinema section features Jean Rollin, gradually transforming into a cult director nowadays, whose genre films, filled with “wanderers, fugitives and seekers”, as Nick Pinkerton puts it, were dismissed in his native France. “They are some of the loneliest films I know… true outsider movies, both in their content and the circumstances of their production.” Rollin was most famously associated with the vampire film, but never went in for traditional scares. “Rollin’s foremost aim is not to terrify but to seduce, entrance, narcotise.” You can catch some of these 70s masterpieces and curios on BFI Player, and Black House Films are overseeing new UK Blu-ray releases.

Also in this issue: long reviews of Jeune femme and the Godard biopic Redoubtable, the early films of Derek Jarman box set, an exploration of sleep in cinema, and the enigmatic finale of Antonioni’s The Passenger.

Features

The Other Side of 80s America

American cinema in the 1980s is usually seen as having thrown aside the character-driven, questing spirit of the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 70s in favour of ‘high concept’ spectacles, cartoonish action and the bottom line, with what interesting pockets that remained bubbling up on the indie margins. But amid the era’s ‘Morning in America’ reckoning, there were some filmmakers who kept the flame burning to make personal, often overlooked films that revealed the other side of Reaganism’s patriotic bluster and hollow optimism. By Nick Pinkerton.

+ A nightmare on Main Street

Behind the façade of 80s corporate cinema, low-budget upstarts were making genre movies that exposed the underbelly of Reaganomics. By Anne Billson.

☞ See also Reagan’s bastard children: the lost teens of 1980s American indie films

Burden of Dreams

Lucrecia Martel’s enthralling, enigmatic Zama follows an 18th-century colonial bureaucrat desperate to escape the tedium of his post in Paraguay, in as pitiless a portrait of the colonial project as it is possible to imagine. By Jonathan Romney.

+ “Mystery is a constant fact of existence”

Argentinian director Lucrecia Martel explains what first attracted her to Antonio di Benedetto’s novel Zama, why the idea of seizing the day is just an empty slogan and what it means to be stuck. By Nick James.

Thoroughly Modern Mädchen

The female characters in the silent and early sound films of the Austrian director G.W. Pabst are rebellious, sexual, intelligent and often outrageous, but always credible and intriguing – exemplified by Louise Brooks’s spellbinding Lulu in Pandora’s Box. By Pamela Hutchinson.

+ Pretty in pink

A recent discovery of Technicolor film fragments at the BFI National Archive includes a fascinating clip of Louise Brooks, the ultimate black-and-white icon, in glorious colour. By Bryony Dixon.

Marion Cotillard: Blood, Sweat and Tears

One of France’s biggest-ever global stars, Marion Cotillard thrives in melancholy, bitter-sweet roles in both Hollywood blockbusters and auteur fare such as Arnaud Desplechin’s Ismael’s Ghosts – an oeuvre that offers a perfect illustration of our culture’s fascination with seeing a beautiful woman cry. By Ginette Vincendeau.

Regulars

Editorial

Island in the stream

Rushes

Our Rushes section

On our radar

Budd Boetticher & Randolph Scott at Columbia; Women in Cinema at BFI Southbank; The Sound of Music on 70mm; Derby, Cannes and Offbeat Jazz and Cinema festivals.

Interview: Alabama goddam

A young black woman refuses to surrender to fear in the Alabama of 1944 in Nancy Buirski’s incendiary documentary The Rape of Recy Taylor. By Kelli Weston.

The numbers: Love, Simon

Charles Gant on US teen comedies since 2000 at the UK box office.

Animation: Orphans of the storm

The Breadwinner, a story of children in war-torn Afghanistan, has universal resonances – and filming it took a global production process. By Nick Bradshaw.

Dispatches: Cinema de maman

One of the few female filmmakers in post-war France, the unfairly neglected Jacqueline Audry paved the way for the likes of Agnès Varda. By Mark Cousins.

Wide Angle

Our Wide Angle section

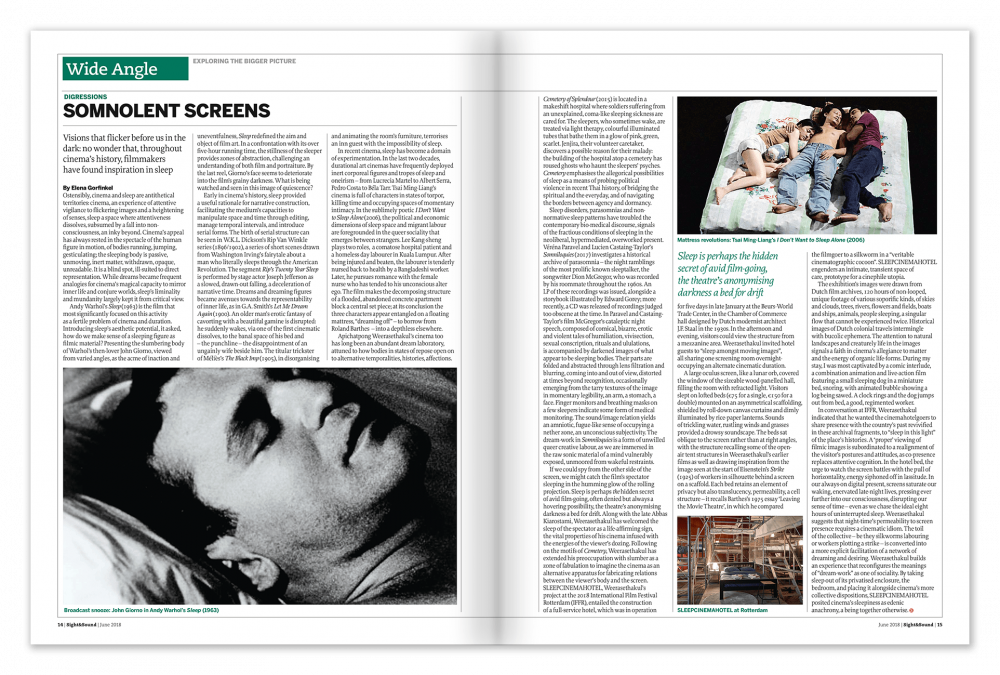

Observations: Somnolent screens

Visions that flicker before us in the dark: no wonder that, throughout cinema’s history, filmmakers have found inspiration in sleep. By Elena Gorfinkel.

Profile: When worlds collide

These days, art needs to reflect more than one kind of reality: American painter/VR artist Rachel Rossin is blazing the trail. By Nick Pinkerton.

Our Festivals section

Festivals

Hong Kong: The dragon’s mark

A fine work by the late young director Hu Bo proved a highlight at a festival abuzz over a pair of controversial staff departures. By Tony Rayns.

Reviews

Films of the month

Jeune femme

Redoubtable

That Summer

plus reviews of

Our Reviews section

Allure

L’Amant double

Anon

Another News Story

Blockers

The Breadwinner

A Cambodian Spring

The Cured

The Deminer

Edie

Entebbe

The Filmworker

How to Talk to Girls at Parties

Ismael’s Ghosts

Lean on Pete

The Leisure Seeker

Mansfield

Mary and the Witch’s Flower

My Friend Dahmer

New Town Utopia

On Chesil Beach

The Outsider

Pacific Rim: Uprising

A Quiet Place

Ready Player One

Revenge

The Strangers: Prey at Night

That Good Night

Truth or Dare

The Wild Boys

Young Karl Marx

Zama

Home Cinema features

Our Home Cinema section

Anatomy of melancholy: the films of Jean Rollin

Sometimes dismissed as genre trash or even softcore porn, Jean Rollin’s films portray a unique landscape of sadness and poetry. By Nick Pinkerton.

Angelic conversations: Derek Jarman Volume One: 1972-1986

A box-set of Derek Jarman’s early films offers a wealth of insights into the work of one of Britain’s greatest artists. By Adam Scovell.

Lost and found: Seven Beauties

Lina Wertmüller’s blackly comic take on masculinity and Fascism earned her an Oscar nomination – why is it now so little known? By Alex Davidson.

plus reviews of

La Chinoise

Gumshoe

Films by Ray Harryhausen

Legend of the Mountain

La Note Bleue

Otley

Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years Volume 2

They Came to a City

Der Todesking

Town on Trial

Viva l’Italia

Television

The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes reviewed by Robert Hanks.

Books

Orson Welles in Focus: Texts and Contexts edited by James N. Gilmore and Sidney Gottlieb (Indiana University Press) reviewed by Ben Walters

Beyond Terror: The Films of Lucio Fulci by Stephen Thrower (FAB Press) reviewed by Michael Brooke

The End of Japanese Cinema: Industrial Genres, National Times and Media Ecologies by Alexander Zahlten (Duke University Press) reviewed by Alexander Jacoby

Letters

Endings

The Passenger

The intricate shot that crowns Michelangelo Antonioni’s beguiling tale of assumed identity only deepens the film’s mystery. By Philip Kemp.

→ Buy a print edition

→ Access the digital edition

→

The BFI Podcast

Listen to our cover writer Nick Pinkerton discuss 1980s cinema with Henry Barnes:

Further reading

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.