Web exclusive

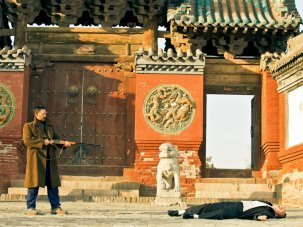

Norte, End of History

Back in 1955 the French critic André Bazin famously described the Cannes Film Festival as being like a religious order, fully-fledged participation in which is like being admitted to monastic life. Certainly the phenomenal number of people wandering around in Cannes with heads bowed, contemplating their BlackBerries with profound solemnity, can reinforce just such an impression.

The deity perched at the pinnacle of this imaginary order is artistic director Thierry Frémaux, whose ways can sometimes seem all too mysterious and inscrutable. I’ve often wondered, for example, what principles of selection designate some films for Competition, while others are consigned to Un Certain Regard.

In an interview with one of the trade papers, Frémaux explained it tersely as akin to the difference between a long and short novel. But Lav Diaz’s masterpiece Norte, End of History in Un Certain Regard is an epic four hours long! And surely quality matters most? Alain Guiraudie’s The Stranger at the Lake, also berthed in UCR [See Geoff Andrew’s report last Saturday], is way superior to anything I’ve seen in Competition, and French to boot! Is the fact it has no stars the deal-breaker?

One journalist suggested that UCR harbours the more ‘intimate’ films. This year, interestingly, there are eight women directors in UCR, but only one in Competition (one more than last year). Do women direct more ‘intimate’ films, whatever that means? And is intimacy somehow lesser? Than what?

Perhaps such matters are simply beyond the understanding of mere mortals. Instead let’s just be grateful for the divine largesse of the aforementioned Diaz’s first-ever screening in Cannes. It’s a situation to savour, since despite the Filipino having a significant cadre of devoted followers internationally, Cannes has persisted in ignoring him hitherto; history shows the festival has a tendency to latch onto (or ‘anoint’) certain auteurs only when they’re already some way into their careers, Wong Kar-Wai being a prime example.

Norte, End of History, Diaz’s 15th film, grapples with big abstract themes – justice, the nature of evil, guilt, fate, love – but keeps them firmly rooted in the concrete particulars of Philippine society. A drop-out law student grows ever more twisted in his take on life, airing political views that could be construed as fascist and deliberately alienating friends and family. Another man, decent and simple, seems incapable of providing for his impoverished family. When the student murders the pawnbroker who lends them both money, as well as her daughter, the other man is mistakenly jailed for the crime.

There are clear nods to Dostoevsky, but the student’s descent into ever more horrific depths is only one element, beautifully counterpointed with the imprisoned man’s spiritual awakening, his wife’s struggle to cope without him and raise their children, and their continued love for each other despite the hand they’ve been dealt. The episodic, unpredictable narrative proceeds by way of a series of stunning long takes, all visually and spatially perfectly choreographed.

It’s a mesmerising experience that grows deeper and broader the longer it goes on, completely justifying its duration. It seems to be pitched in a completely different key to the other films I’ve seen in Cannes this year, with its own rhythm and rules, a different mode of address to the viewer, the ambition to reach for – and attain – a metaphysical dimension. Fremaux in recent years has risked putting the likes of Colossal Youth and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives in competition, so why not this film, which stands comparison with them. Did its length preclude its selection?

The 14th July Girl (La Fille du 14 juillet)

There was only way one to go after that, but I wasn’t prepared for quite such a steep descent. A critic friend urged me to check out the first feature of Antonin Peretjatko, the French comedy The 14th July Girl (La Fille du 14 juillet), in Directors’ Fortnight, citing the two Jacques, Tati and Rozier, as its guiding influences. I raced up the Croisette to see it, but probably should have lingered a bit more on the phrase ‘French comedy’, since it’s quite often oxymoronic in my experience; and so it proved.

To be fair, this is another film tackling subjects such as the financial crisis, the lack of jobs, imbecilic political leaders, but with an unusually light-handed satirical touch: the eponymous girl is recently graduated but unable to find work, so gathers a bunch of friends to head south for a holiday. The antics that ensue (given 60s retro stylings and soundtrack) put me in mind of those Parisian pals of Pippa Middleton who think it’s hilarious to point replica guns at photographers; I suspect they’ll love this. (Maybe it’s not in fact a comedy but a documentary of contemporary goings-on amongst gilded youth in the Marais?) It seemed further proof that life can provide few spectacles less edifying than Parisian bobos being zany and post-modern.

One man’s meat and all that. Clearly it’s best not to lend too much credence to others’ views, but how not to, when Cannes is fuelled by precisely all that hot air. Everyone – and I’m one of the worst offenders – is constantly thrusting their opinions on everyone else, and eager in turn to hear about the latest discovery. It’s immensely pleasurable, but after eight days or more of it, you can start to long for a bit of verbal fasting.

If Bazin was right about Cannes, perhaps its cinephile monks and nuns should vow to keep their counsel, refrain from holding forth. It could put a whole new enticing spin on the phrase ‘silent film festival’.

-

Cannes Film Festival 2013 – all our coverage

See our previews, first-look reviews, festival roundups and awards reactions.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.