Web exclusive

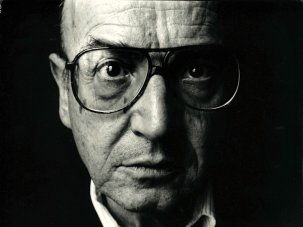

Lav Diaz’s eight-hour Melancholia (2008)

Lav Diaz calls his most committed spectators “warriors”. Coming to his films well-fed and well-rested, they curl a lip at the idea of the interval, and gauge the endurance of the human bladder quite differently from the likes of Alfred Hitchcock.

Yet, sitting round a table after an eight-hour screening of Melancholia (2008) at the Star and Shadow cinema in Newcastle, Diaz outlines for his British initiates the less intensive kind of picturegoing he will encourage when he takes his films on the road in his native Philippines. With films this long, he says, you can go off and plough a field, prepare a meal or make love to your wife [sic] before returning to the screen. One way or another, I missed the last five hours.

Slow exhibition

Hitherto all but unknown in the UK, Diaz’s films were being shown as part of the Slow Cinema Weekend, which was in turn part of AV Festival 12: As Slow As Possible, a month-long extravaganza devoted to slowness in music and the visual arts staged at various sites throughout the north-east during March.

The more-or-less conventionally cinematic strand encompassed the likes of Pedro Costa and Jia Zhangke, but many of the gallery artists on display also use the (just about) moving image. James Benning, whose installation One Way Boogie Woogie 2012 had its world premiere in Sunderland, and Ben Rivers – now among Diaz’s warriors – belong comfortably enough in both camps, or suggest their partial convergence.

The Slow Cinema Weekend itself was an unusual and exemplary festival-within-a-festival, distinguished by its small number of films in a field where unwarranted live-blogged, tweet-streamed abundance, and consequent fatigue, are the norm. (“I don’t make films for festivals,” the filmmaker character in Diaz’s Century of Breathing tells a programmer whose deadline he has broken. “I make them for cinema.”)

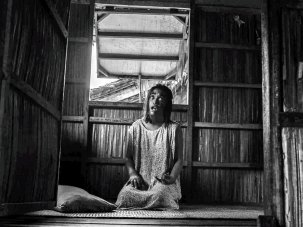

Lisandro Alonso’s Los Muertos (2004)

AV’s commitment to slowness encompassed slow distribution, slow exhibition and slow appreciation, as well as merely slow films. Devoted to four directors – Diaz, Rivers, Fred Kelemen and Lisandro Alonso – the weekend threw up just one schedule clash in four days.

Slow distribution

The most recent of Alonso’s films at AV was first shown in 2006 and the most recent of Kelemen’s as long ago as 1999. Yet it would hardly be accurate to describe their screenings in Newcastle as retrospectives. It can’t be a retrospective if the films were scarcely visible in the first place, and it isn’t a revival if they weren’t allowed to live first time round. Even in the digital era, their films are not easily obtained in Britain – Kelemen’s not even as .avi files, possibly by choice. “Just as a theatre production only exists in the moment when it’s performed, a piece of music only when it’s played,” he has said, “a work of film art only wakes when it’s projected on to a screen in a cinema.”

Frost (1997), never given a British release, is elemental, experiential cinema, of a quality that fully justifies its maker’s uncompromising stance. A gruelling trek across the former East Germany in the company of an abused wife and her young son, it is built of fire and ice, extremes of barely candlelit interiors and great snow-covered fields of white light. Like the follow-up Abendland (1999), which translates as both “evening land” and “the West”, also given a rare outing in Newcastle, it evokes a kind of perpetual fin de siècle Europe, as current now as then, in long, intricately choreographed takes that give Kelemen’s locations an almost corporeal presence.

Slow appreciation

The AV programme was, in Slate writer Dan Kois’s phrase, a big bowl of “cultural vegetables” – that is, something that demands concentration, withholds immediate pleasures and otherwise interferes in one’s evening routine – and inevitably the question came up in discussion.

Fred Kelemen’s three-hour-twenty-minute Frost (1997)

Cutting through the thickets of posturing populist attacks and disingenuous defences that have grown up around the subject, Ben Rivers described his experience of seeing Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964) for the first time only after several attempts, making no pretence that the film is easy, but rather admitting to finding difficulty difficult – yet valuable. (If it helps, he’s a big Eastbound & Down fan too.)

At the same time, not all slow cinema is all that slow. The length of a shot, on which much of the debate revolves, is a quite abstract measure if divorced from what takes place within it, and it is far from unusual for a Kelemen shot to move from a landscape to a close-up, by way of numerous points between.

As he put it himself in a recent interview with Cinema Scope about Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse, on which he served as cinematographer, “Inside this shot are many individual shots, each one emphasising a particular idea.” It’s a construction more reminiscent of Sergei Eisenstein, arch-theorist-cum-practitioner of montage, than of André Bazin, patron saint of patient contemplation.

Slow action

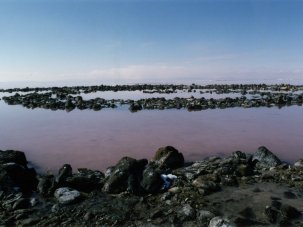

The two Rivers films on show, Two Years at Sea and Slow Action, a quasi-documentary akin to Werner Herzog’s Fata Morgana (1971), are yet more heterogeneous in form, but reveal nonetheless striking affinities with the slow cinema canon.

Parts of Two Years, an Alonso-esque study of man in nature, in this case a remote part of Scotland, belong to what slow cinema scholar Matthew Flanagan, adapting a line from Thom Andersen, calls the “cinema of walking”, highly appropriate to Kelemen; yet it is as meticulously edited as Kelemen’s shots are planned. Like Kelemen’s films, it conjures up from thickly textured reality an imaginary geography, and a sense of time’s passage, all of its own.

Ben Rivers’ Slow Action (2010)

Diaz’s films, meanwhile, really are all that slow. Manohla Dargis, during the “cultural vegetables” controversy, wrote that slow films “restore a sense of duration, of time and life passing”; Diaz’s are not the sense but the thing itself.

Melancholia, from what I saw, is a not unconventional narrative film with actors, except that each scene, usually covered in one static shot, takes a long time to end. Diaz’s response to critics that “Time is a very Western concept”, introduced to the Philippines by the Spanish, doesn’t really address the problem: the modern conception of time as currency had to be imposed in the West too. His view that the first principle of art is “please yourself” has to go for the viewer too.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.