Awards

International jury prizes

Golden Bear for Best Film

Touch Me Not by Adina Pintilie

Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize

Mug (Twarz) by Małgorzata Szumowska

Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize

The Heiresses (Las herederas) by Marcelo Martinessi

Silver Bear for Best Director

Wes Anderson for Isle of Dogs

Silver Bear for Best Actress

Ana Brun in Las herederas (The Heiresses) by Marcelo Martinessi

Silver Bear for Best Actor

Anthony Bajon in La prière (The Prayer) by Cédric Kahn

Silver Bear for Best Screenplay

Manuel Alcalá and Alonso Ruizpalacios for Museum (Museo) by Alonso Ruizpalacios

Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution

Elena Okopnaya for costume and production design in Dovlatov by Alexey German Jr.

Panorama audience awards

Winner (fiction film)

Profile by Timur Bekmambetov

2nd place (fiction film)

Styx by Wolfgang Fischer

3rd place (fiction film)

L’Animale by Katharina Mueckstein

Winner (documentary)

The Silence of Others by Almudena Carracedo, Robert Bahar

2nd place

(documentary)

Partisan by Lutz Pehnert, Matthias Ehlert, Adama Ulrich

3rd place

(documentary)

O processo by Maria Augusta Ramos

Our critics’ highlights

Nick James

Victory Day (2018)

The most perfect film at Berlin was Sergei Loznitsa’s Victory Day, a documentary about crowds flooding into Berlin to visit the Great Patriotic War memorial built by the Soviets in Treptower Park. The crowd includes nationalist biker gangs, but everyone is in a great mood singing patriotic songs and flaunting red flags, red carnations and chestfuls of medals, presumably won by their grandparents. It was the Soviet army that defeated the bulk of the German army. But when you hear the Cossacks being praised you might also think of the pogroms or the mass rape of German women in Berlin in 1945. The people celebrating the freeing of Europe from the Nazi yoke also represent the upsurge of nationalism. The ironies rebound and rebound.

I loved Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs, found Alexei German Jr’s Dovlatov fascinating, Guy Maddin’s The Green Fog a thrill, Rupert Everett’s The Happy Prince a real surprise, Marcelo Martinessi’s The Heiresses a quiet, subtle achievement and Małgorzata Szumowska’s Mug wonderful. The programme seemed upside-down somehow and that it grew stronger and stronger was better than expected.

Paul O’Callaghan

Touch Me Not (2018)

I’m among a seemingly small minority heartened by Touch Me Not’s awards success. Adina Pintilie’s earnest exploration of sexual identity is undoubtedly a little rough around the edges, but I’m baffled by some of the vitriolic responses I’ve seen to this ambitious, empathetic debut feature.

That being said, my pick for the Golden Bear would have been Alexei German Jr’s Dovlatov. This deft, freewheeling portrait of an under-appreciated writer flying by the seat of his pants through 1970s Leningrad hooked me from the word go. Milan Marić delivered by far my favourite performance of the festival as the titular man of letters, struggling to conceal his deep-seated frustration behind a mask of amiability and deadpan humour.

I saw Madeline’s Madeline weeks before the Berlinale kicked off, and little that I’ve watched since can hold a candle to Josephine Decker’s delightfully strange meditation on teenage mental illness, authorship and cultural appropriation. But as usual, the festival’s queer selection served up a few pleasant surprises. Jordan Scheile’s The Silk and the Flame is a bracingly intimate, deeply haunting documentary about a gay Chinese man stifled by his traditional family. And Tranny Fag (Bixa Travesty) is a formally playful portrait of Brazilian trans musician Linn da Quebrada, a swaggeringly defiant hip hop artist pushing LGBT activism in a thrilling new direction.

Ian Mantgani

Madeline's Madeline (2018)

Madeline’s Madeline, the third feature from Josephine Decker, is the director’s most satisfyingly well-rounded film yet and the clear highlight of my Berlinale. The bleary, dissonant, emotionally bracing style that Decker has developed with cinematographer Ashley Connor is matched by a psychologically searching and generous portrayal of the fine line between psychosis and creativity, following the freakout moods of a high school performing arts student played by Helena Howard in a star-making film debut. The climax explodes into an assaultive, confrontational musical number recalling great alternative movie musicals like All That Jazz and Dancer in the Dark, and by the end we’ve seen a dizzying act of film experimentation, investigation of subtextual tangents and portrayal of youth on the brink.

Also terrific, from what I saw: Hong Sangsoo’s tender, incisive café drama Grass; Guy Maddin’s tableaux short Accidence and hour-long San Francisco supercut The Green Fog; Steven Soderbergh’s iPhone-shot semi-political stalker thriller Unsane; and Ricky D’Ambrose’s spare, haunting, sarcastic and elusive portrayal of New York intellectuals in moral decay, Notes on an Appearance.

Geoff Andrew

The Green Fog (2017)

From a festival fecund in good if far from extraordinary films and utterly bereft (at least for me) of masterpieces, it’s hard to single out one title as the best. Still, there was nothing I found more consistently enjoyable more than The Green Fog, by Guy Maddin and Evan and Galen Johnson. Brilliantly assembled from hundreds of clips from movies and TV series set in and/or shot in San Francisco and its environs, the compilation more or less re-tells the story of Hitchcock’s Vertigo (with various intriguing and imaginative digressions) with dozens of actors standing in for the characters played by James Stewart and Kim Novak. As a meta-narrative which sheds fresh light on filmic storytelling, it’s intellectually stimulating; in the end, however, what makes the film special is that it’s very, very funny.

The Green Fog played in the Forum, as did a likewise modest and offbeat gem, Corneliu Porumboiu’s Infinite Football, which also manages to be philosophical and amusing. From the competition my favourites were Małgorzata Szumowska’s unfortunately titled Mug, Marcelo Martinessi’s The Heiresses and Markus Imhoof’s documentary Eldorado, though only the first of these provided quite as much outright fun as Steven Soderbergh’s out-of-competition Unsane, a psychological thriller shot with a cellphone though hardly so as you’d know it.

Patrick Gamble

An Elephant Sitting Still (2018)

This year’s Forum sidebar was once again a rich source of innovative and thought-provoking films at the Berlinale. The standout was Chinese director Hu Bo’s first, and sadly final film, An Elephant Sitting Still, a four-hour opus charting the separate experiences of three characters subsumed in an indifferent world. The result is an immersive perspective on the disillusionment and sense of emptiness experienced by those living in a society marked by rampant individualism, effectively conveyed through long, hypnotic tracking shots that cling to the character’s haunted faces as they search for an escape. Hu sadly took his own life after completing the film and his work here seems to hint at the darkness that consumed him.

Other films in the Forum that impressed include Josephine Decker’s emotionally bracing drama about the fragile line separating creativity and insanity, Madeline’s Madeline; Thai director Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit’s ephemeral tapestry of various perspectives on death, Die Tomorrow; and Corneliu Porumboiu’s Infinite Football. Porumboiu’s second soccer themed documentary follows Laurențiu Ginghină, a lowly pen-pusher who has a plan to revolutionise the rules of the beautiful game to give the ball more freedom, which again proves Porumboiu is a refined explorer of the intersection between sport and politics.

Michael Leader

Minatomachi (Inland Sea, 2018)

If I were to spotlight just one gem in the rough that was this year’s Berlinale, it would be Japanese director Soda Kazuhiro’s Minatomachi (Inland Sea), a freeform black-and-white documentary portrait of a fishing town, filled with formidable old folks and countless cats. The seventh in his Observational Film series, Minatomachi casually, yet carefully follows the daily routines of several octogenarian residents, celebrating their lives and their livelihoods, while mourning for a generation that will soon be lost to history.

Elsewhere in the Berlinale’s Forum and Panorama programmes, I enjoyed debuts and deep-dive discoveries, including Amiko, a scrappy but spirited first feature from 20-year-old film school drop-out Yamanaka Yoko, and Austrian director Katharina Mückstein’s coming-of-age drama L’Animale; both films were fresh in form and voice, with a keen focus on the desires and shifting, idiosyncratic identities of their young female protagonists.

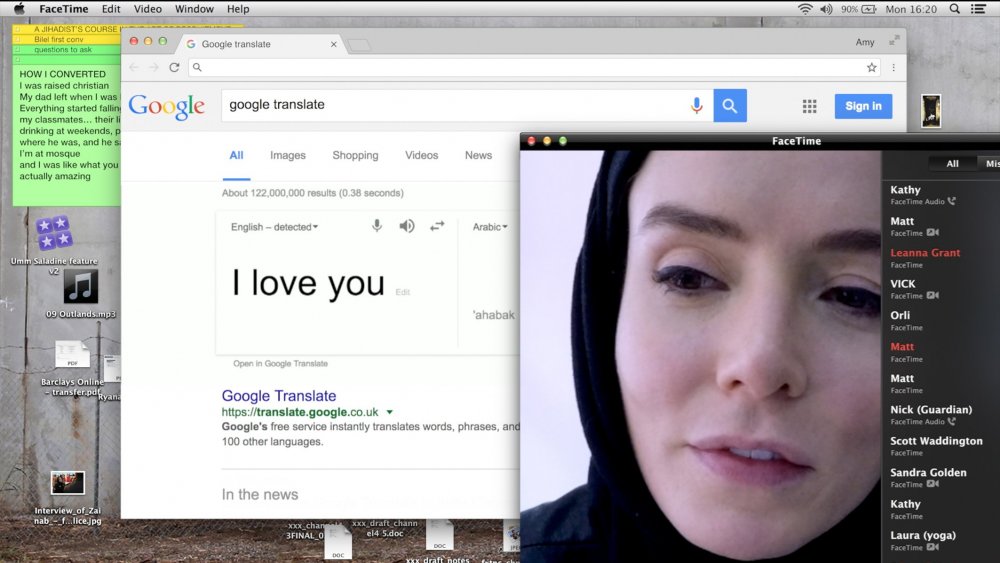

And then there was the wildly entertaining Profile. Best known for the overblown antics of Wanted and Night Watch, Timur Bekmambetov pilfers a found-footage gimmick from 2014 horror Unfriended, which he produced, to follow an investigative journalist’s attempts to expose an online ISIS recruitment campaign – told solely through the many open tabs, browser windows and Skype chats cluttering up her laptop screen. A little preposterous, perhaps, but certainly compelling – and a hit with the Berlin public, who gave the film the Panorama Audience Award.

Simran Hans

Profile (2018)

On the basis of pure viewing pleasure, I’m batting for the bonkers Profile, which won the festival’s Panorama Audience Award. Timur Bekmambetov’s adaptation of bestselling book In the Skin of a Jidhadist plays out almost entirely as a computer screen, hyperactively clicking between Facebook, Skype and a disquieting amount of open browser tabs to tell the lurid, absurd tale of an ambitious, reckless freelance journalist who attempts to catfish (and seduce) a handsome ISIS recruiter for a career-making story. The campy thriller’s narrative logic falters fast, and it requires an inordinate suspension of disbelief to ‘work’, but for visceral, nerve-shredding tension it deserves a robust round of applause.

I was also impressed by Czech director Jan Gebert’s commanding debut feature When the War Comes, a slippery, disturbing observational documentary about a far-right fringe group called the Slovak Recruits. An armed group of teenagers in outdated military gear, they’re an intimidating bunch who lack political legitimacy, and so aren’t seen as a threat by the police. Gebert frames this negligence as its own form of slick complicity.

Ella Kemp

L’Animale (2018)

In a programme full of experimental and abstract approaches, Katharina Mückstein’s L’Animale stood out as a comfortable relief. An Austrian coming-of-age story, it follows Mati in the lead up to her final exams at school, seeking greater meaning and emotional balance before the start of the rest of her life. On paper it’s nothing new, but the knowing references to recent films about sexual awakening, including Call Me by Your Name and Stranger by the Lake, and classics unpicking existential angst like Magnolia, give the narrative an awake likability. Stylistically sharp, from the poised feline characters to the strobe-soaked nightclubs, it’s a memorable watch, a lesson in loving for all ages.

Reflecting a post-#MeToo landscape by shifting the spotlight to lesser-heard voices, Unsane and Madeline’s Madeline brought intense and stirring power to the Berlinale. Through different stories of gender identity and mental instability, they blur the line between trust and performance as young women resist their shackles; equal parts empowering and upsetting, both films ask preoccupying questions that stretch way past the confines of their fiction.

Jonathan Romney

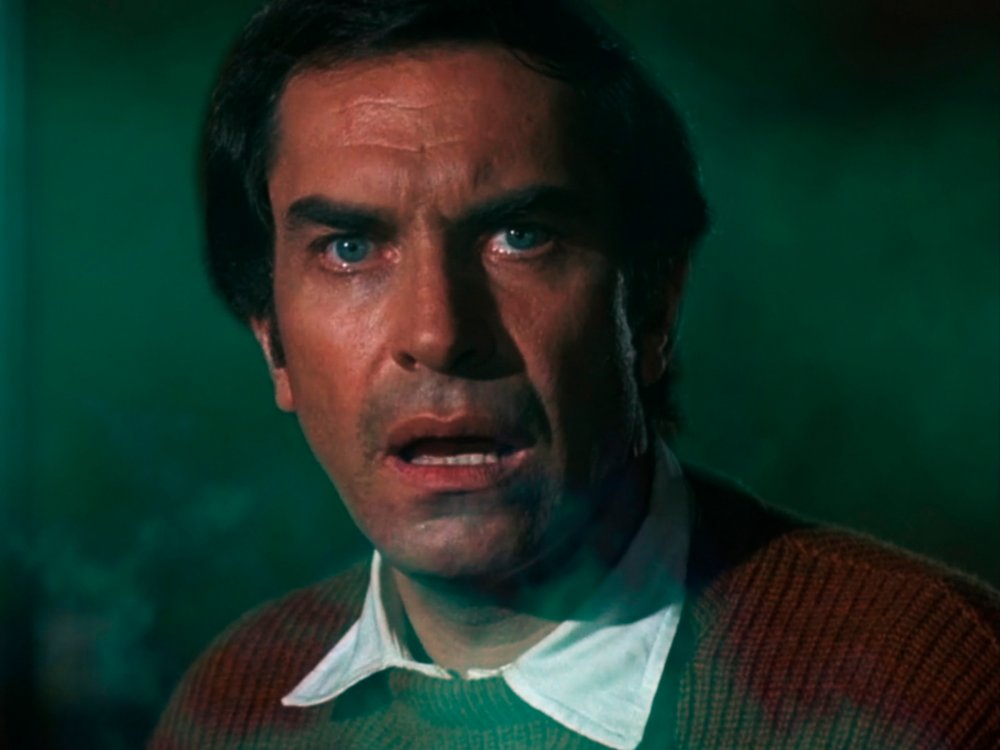

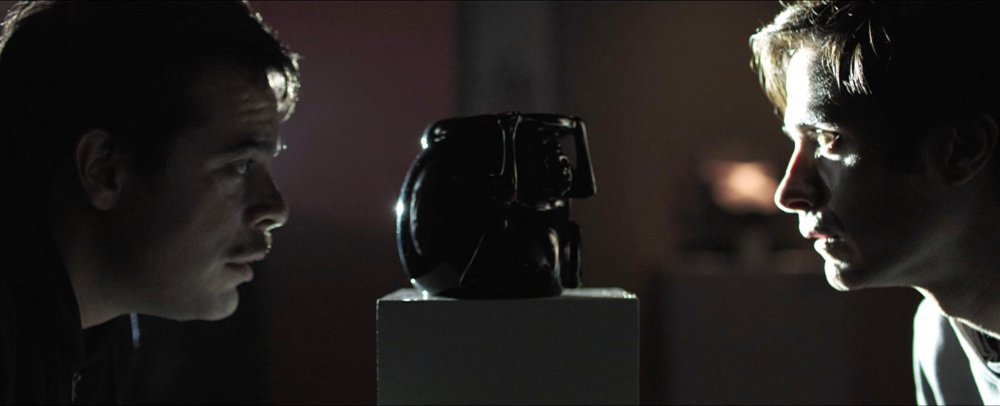

Museum (2018)

In a Berlinale competition dishearteningly low on pleasure – after the euphoric opening flourish of Isle of Dogs – Alonso Ruizpalacios’s Museum was a much-needed tonic in the closing stretch. Expectations were high for this second feature from the Mexican director of the nouvelle vague-toned Güeros, and Museum showed him revelling in his confidence. It’s a heist movie, or part of it is: a tribute to films like Rififi and Topkapi, with Gael García Bernal and Leonardo Ortizgris as friends who plan to steal a collection of prized Mayan artefacts. They succeed, in an extraordinarily sleek caper-referencing sequence, but that’s just part of a stylistically exuberant film which also combines road movie, family comedy and meditation on the contradictions of archaeology.

Also a joy in the Forum section: the dizzy cinematic thought-salad of Guy Maddin’s The Green Fog, a sampladelic ‘remake’ of Vertigo stitched from clips of myriad films & TV series made in San Francisco, with an unwitting all-star cast including Joan Crawford and a perpetually bewildered Chuck Norris. What Christian Marclay’s The Clock was to time, The Green Fog is about place – although its San Francisco is a dream location you could only visit in the movies, and in a Maddin work at that.

Michael Pattison

11 x 14 (1977)

At the risk of being ‘that guy’, the best film I saw in Berlin this year was a repertory screening. Restored by the Austrian Filmmuseum and playing from a new 35mm print, James Benning’s 11 x 14 (1977) exploits and emphasises found symmetries (architectural, infrastructural) and the perpendicularity of the film frame itself. Benning anticipates the more rigorous structure of later works but has a consciously playful go at something resembling a narrative too, teased at through the repeated use of actors, colours and sounds: here the song is Dylan’s Black Diamond Bay, heard first in its entirety as two lovers embrace on a bed, then again to accompany the shot of a billowing chimney (Ruhr’s hour-long equivalent of the latter sequence came 32 years later).

In L. Cohen, a new 48-minute fixed-frame single-take landscape work that screened on loop as part of a Forum Expanded exhibition, Benning’s song of choice is Leonard Cohen’s Love Itself; I took it as both a bathetic gag and a sincere emotional gesture, hearing it as I did after the film had given me the single most stirring image-sound transition of this year’s festival – a real-time solar eclipse over an oil field within visible distance of Oregon’s Mount Jefferson. The earth turns black – for a moment.

Three other highlights, in brief. The captivating Yama – Attack to Attack (1985), whose reputation precedes it as the labour documentary whose directors, Mitsuo Sato and Kyoichi Yamaoka, were both murdered in separate attacks by far-right anti-union yakuza members because of their involvement in its making. No prizes, meanwhile, for guessing the subject matter of Heinz Emigholz’s Two Basilicas: over 35 minutes, and what seems to be an even quicker pace than usual, the German architecture-landscape filmmaker contrasts two churches, one in Copenhagen built across decades and another in Orvieto – built across centuries. And finally, Ted Fendt’s Classical Period, which I saw twice, is a wry, lo-fi rendition of Philadelphian autodidacts in relentless pursuit of knowledge. Weird, rough, kind of great – I watched it thinking of another recent film by Benning that wasn’t in Berlin: Readers.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.