Web exclusive

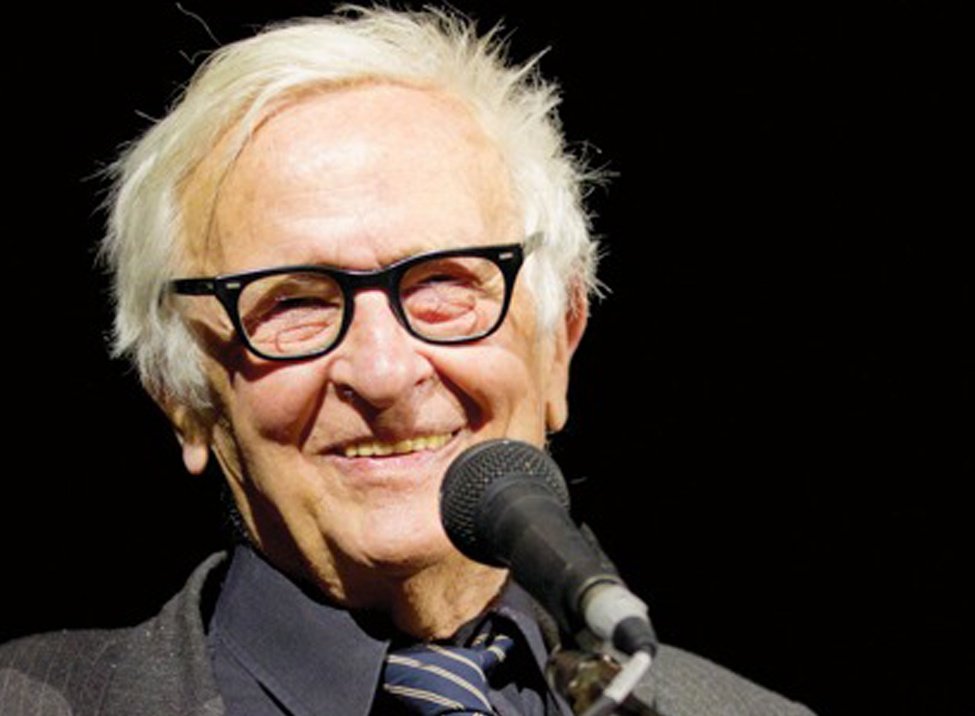

Albert Maysles

“There’s so much that has to be known but isn’t because it wasn’t filmed properly and made into a good film”

— Albert Maysles

This year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest marked two firsts: the festival’s shift up the calendar from November to June, and the inauguration of its Lifetime Achievement award. Both bets paid off splendidly. The summer reschedule meant more buzz from both the movies and the delegates (I hesitate to call them all ‘audiences’, given the festival’s increasing alter-life as an industry pitching forum): the films plucked from IDFA, Sundance, even Cannes were fresher, and Doc/Fest’s ‘premiere-sharing’ deal with the newly gazumped Edinburgh saw a number of filmmakers flying in for both; they arrived into a sunny summer Sheffield whose few flecks of rain only heightened attendees’ pleasure at being able to circulate al fresco between events and venues the rest of the time.

|

Sheffield, UK | June 2011 |

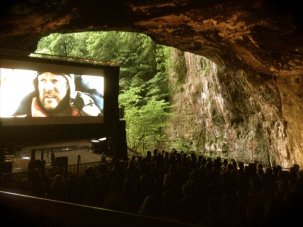

As for the premiere Doc/Fest Lifetime Achiever: Direct Cinema’s Albert Maysles (whose brother and collaborator David was recently joined by their fellow vérité trailblazer Richard Leacock shooting the great reality doc in the sky) presided over the festival like a guiding spirit, his genial beam and exemplary moral lessons permeating the atmosphere (and I missed him introducing the 1975 classic Grey Gardens on Devonshire Green, an event that harnessed both Maysles and the weather).

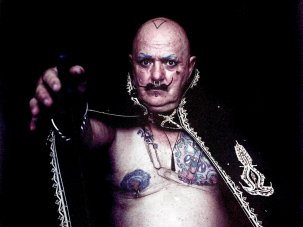

“People would much rather reveal than conceal,” he told the audience after a screening of Muhammad and Larry, a touching, elegantly and expertly even-handed portrait of criss-crossing boxing allies Muhammad Ali and Larry Holmes before and after their 1980 Heavyweight Championship fight, recently completed with Bradley Kaplan for ESPN Films.

“I feel confident that almost anybody I want to film will let me because I’m confident I can do a decent job of respecting them and letting them come forth with whatever they’ve got to say,” he continued two days later from the stage of the majestic Lyceum Theatre. “We can do so much in the process of documentary making to achieve what the anthropologist Margaret Mead called ‘finding common ground’.” He had more reminiscences (and exhortations) for his City Hall award party, too, but my mind diverts to the star-spangled hula hoop artiste who followed him on stage. I’m still trying to figure out the connection.

Adam Curtis’s All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace (2011)

Speaking of speakers, the festival almost ODed this year: other interviews and masterclasses showcased John Akomfrah, Nick Broomfield, Molly Dineen, Alex Gibney, Steve James, Bruce Parry, Leonard Retel Helmrich and Morgan Spurlock.

I got wrist-ache scribbling down Adam Curtis’s pronouncements on the disconnect between Grand Journalism and people’s emotional experiences, our individualistic “market or Google” myth of democracy, and the lack of progressive vision in politics and the media. Television had split its cares between aloof factual reporting and “feeding the rat of the individual”; it needed to “pull back and allow people to see what surrounds us, connect our feelings to the bigger events”. Twitter was deemed “a fake, narrow, desiccated… non-sociological view of the world” – not to mention “a self-aggrandising smug pressure group.” And Curtis had just discovered ‘hauntology’, the “idea that we’re completely trapped by our past and culture,” and confessed he certainly felt “trapped in retroland”.

“We’ve retreated from the idea that society is more than a mass of individuals,” Curtis summarised. “All I’ve ever done in my films is point out where power flows through society.”

I chose Curtis’s talk over the chance to see Steve James (Hoop Dreams) and author Alex Kotlowitz’s The Interrupters, a year-in-the-life portrait of three Chicagoan ex-gangsters turned ‘violence interrupters’ which duly won the Special Jury Award. (Dogwoof are bringing it to the UK in August.) But crime, punishment and the often brutal might of the state constituted one of the themes of my viewing card.

Marshall (Street Fight) Curry’s If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front (winner of the Documentary Editing award at this year’s Sundance) is a sad, cautionary fable about playing vigilante eco-warriors and attempting to best an unaccountable state with violence. Michel Wenzer’s California prison doc At Night I Fly is an unexpectedly moving tone poem about transcending fear, loathing and isolation and finding one’s spirit behind bars.

The Doc/Fest audience award meanwhile went to Michael Collins’ Give Up Tomorrow; admittedly the Saturday screening appeared to be half-full of the film’s NGO backers, but it patiently and beautifully relates the flabbergasting, gross injustice of Filipino student Paco Larrañaga’s death sentence for a faraway, never-proved sex murder, and sketches a Filipino justice system so absurdly corrupt you couldn’t make it up. The film was accompanied by Elle Sillanpaa’s stark, resourcefully simple and heart-rending 20-minute short Guerillera, built around the testimony of former Colombian guerrilla fighter (and mother) turned London cleaner.

Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles (2011)

Two years after Winnebago Man, Ben Steinbauer’s entertaining investigation of the potty-mouthed viral-video phenomenon, screened at Sheffield, two comparable forays into the world of cult culture, underground mysteries – and sad old men – screened this year.

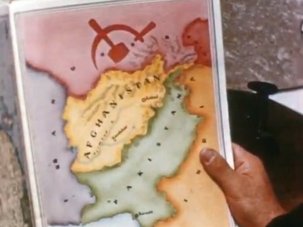

First-time director Jon Foy’s Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles is a diaristic recounting of three Philadelphia geeks’ gumshoe work trying to make sense of the innumerable, cryptic tiled murals that for years appeared like urban crop circles on the streets of their hometown and abroad; it’s a slim, loose and perhaps two-dimensional movie, but certainly communicates the infectious, Pynchonesque eeriness of the mystery.

Richer both aesthetically and thematically is Matthew Bate’s Shut Up Little Man! An Audio Misadventure, about the ‘audio verité’ recordings made of their drunk, rancorous neighbours (“If you wanna talk to me then shut your fucking mouth!”) by two San Francisco flatmates in the late 1980s, which spread like wildfire through the city’s art scene, inspired a play and several erstwhile film projects and still keeps their keeper in income. Wittily and energetically illustrated and edited, the film is two parts rollicking retrospective adventure, one part thorny moral quandary as it goes in search of the original unwitting performers.

Phnom Penh Lullaby (2011)

Finally, I counted three great films from the heirs of Maysles. Polish debut documentarian Pawel Kloc’s Phnom Penh Lullaby is a bleedingly empathic portrait of a poor, dysfunctional bi-racial couple trying to scrape by and hang together; she’s a former prostitute with a trail of children by different errant men, he’s a pasty-faced, good-hearted Israeli expat who scrapes a living reading tarot cards on the side of the street. The film is similarly gruelling and trying, but achieves a stunning intimacy.

Leonard Retel Helmrich’s Position Among the Stars concludes his trilogy of super-immersive Indonesian family studies (The Eye of the Day, The Shape of the Moon) – and hones his “single-shot cinema” technique – finding his microcosm of the nation now rent by consumerism on top of political, religious and urban/rural divides.

The jury also gave a well-warranted honorary mention to music-video director Alma Har’el’s Tribeca festival winner Bombay Beach. A strange, stunning, sui generis series of snapshots of three diverse characters who have washed up in the faded erstwhile tourist town beside California’s spoilt Salton Sea, it occasionally breaks out into dance scenes choreographed to music by Beirut and Bob Dylan – on the logic that we reveal ourselves uniquely when we dance. And yet for all its formal boldness, the film felt just a short leap from the shot of Keith Richards tapping his snakeskin boot to the playback of ‘Wild Horses’ in the clip from Gimme Shelter (1970) that Maysles showed us on stage. As he remarked afterwards: “I seem to bet on the right person at the right time – in the right shoes.”