Web exclusive

Joonas Berghäll and Mika Hotakainen’s Steam of Life

One Saturday in late November, while dragging my luggage from Central Station towards the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) press office, I found myself walking alongside a rather odd funeral convoy: four men in formal gear were rather nonchalantly carrying a casket while being frantically photographed by some passers-by. The Dutch words on one side of the casket remained incomprehensible until one of its followers explained that it was Hamlet’s soliloquy. Confronted with the Dutch coalition government’s recent spending review, Amsterdam’s artistic community had decided that silent suffering was not an option and was headed for the city’s Leidseplein (coincidentally, IDFA’s iconic former location) to protest, in eccentric fashion.

|

International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands | November 2010 |

Later that afternoon, while I was queuing to collect my first batch of tickets, the aggrieved Amsterdammers gathered to ‘scream for culture’ as part of a countrywide protest against the government’s looming 25 per cent spending cuts to the cultural sector. Although IDFA’s director Ally Derks (who is to receive the Doc Mogul Award for an outstanding contribution to the documentary culture at the forthcoming Hot Docs festival in May) insisted that the festival was not in danger, as it relies on the government for only a quarter of its budget, yellow ribbons were available throughout for everyone opposing the proposed culture cuts.

This year IDFA heeded previous criticisms of its size by spreading the same number of films it screened last year across one extra day. Since my last visit three years ago, the new location in Rembrandtplein around the gorgeous art deco Pathé Tuschinski theatre (where IDFA relocated on the occasion of its 20th anniversary in 2007) has become more compact, with more venues secured around Rembrandtplein and two new halls acquired slightly further away at the Brakke Grond venue. And the not-so-recent habit of coordinating festivals with tourism and leisure opportunities materialised as a noisy, almost hysterical Christmas market, surrounding IDFA’s headquarters with a record number of lighted Santas and an intoxicating smell of waffles.

If one were to single out IDFA’s main achievement over the years it would probably be its ability to cultivate, through a carefully calibrated selection and its range of sidebar programs, one of the world’s most docuphile local audiences. Long before the current hype for political and activist documentaries, IDFA was attracting the most vibrant domestic audience that a documentary filmmaker could wish for.

While this is surely an achievement to be praised, the need to cater to a public that holds a largely thematic interest in documentary poses its own set of problems, the most stringent being the need to produce events able to hold general interest. This year I found a more drastic separation between events targeting the professional and lay audiences: while most of the specialist talks and panels have become unavailable to the visitor unable to secure the ‘right’ professional badge, the Daily Talkshow, fronted by actress and television presenter Daphne Bunskoek, had all the liveliness and glamour needed for a daily broadcast but lacked the insight and inquisitiveness expected by most of the professional audience.

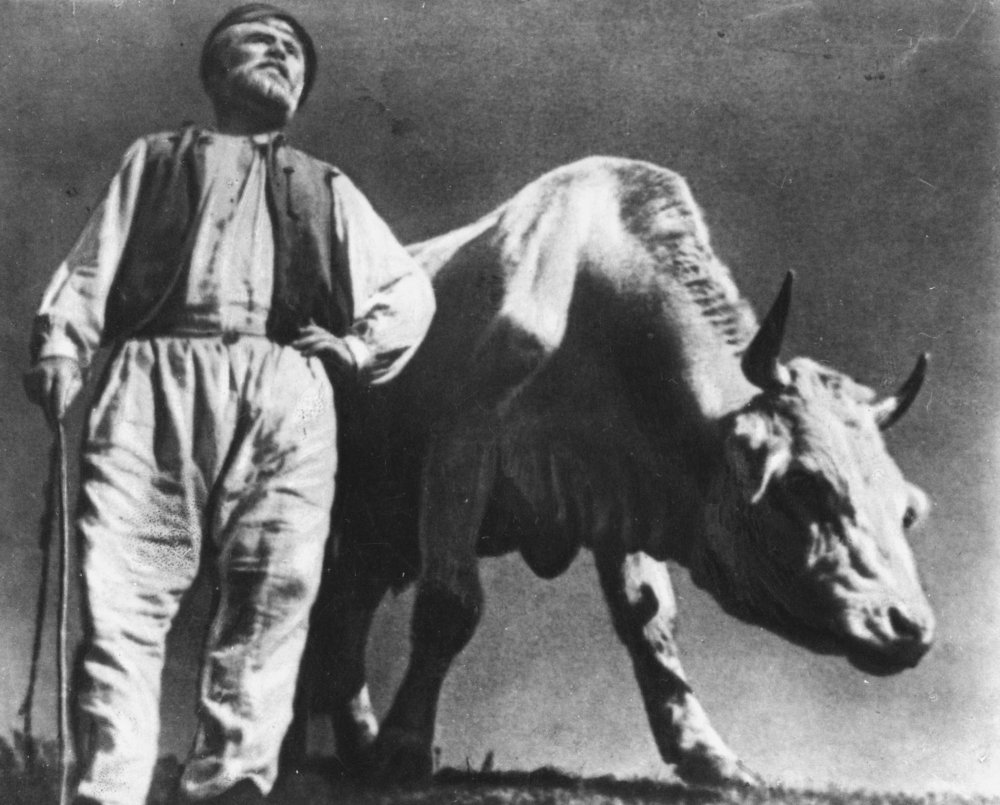

Doc or not? Alexander Dovzhenko’s Earth

Last autumn the New York Times’ A.O. Scott wrote about the difficulty of defining documentary today, given the variety and heterogeneity of options that appear to fragment it “almost to the point of anarchy”. For the visitor approaching IDFA’s feature-length selection with such expectations in mind, this year’s crop appeared slightly unadventurous, although solid and rewarding in terms of the strength and assurance of the films in the major competitions. With only four days to spend in Amsterdam, I still crossed paths with a great sample of beautiful, compassionate and affecting films. One salutary aspect was the programmers’ ability to navigate the avalanche of topical ‘macro’ stories documented with varying degrees of aesthetic achievement, and to retain a steady interest in strong ‘micro’ approaches that obliquely illuminated larger social and political canvases.

The only film in a non-competitive program that I caught was the Finnish gem Steam of Life (Joonas Berghäll and Mika Hotakainen, 2010), a surprisingly minimalist and poetic contrast to today’s analytical or argumentative doc crop. Shot with acute sensitivity inside a number of Finnish saunas and steam rooms, featuring naked men talking about their lives, it plays at a slow pace and allows for long stretches of silence. It is a genuinely moving meditation on Finnish masculinity.

Speaking of the Finns, this year it was the turn of filmmaker Pirjo Honkasalo (The Three Rooms of Melancholia, 2004) to curate her all-time top ten documentaries (the festival invites one documentary master each year to compile this special retrospective programme). Honkasalo casually pushed the boundaries of her remit by including Alexander Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930) and Visconti’s The Earth Trembles (1948): “One needs poetry to reach the truth,” she explained to one of IDFA’s Daily Talkshows.

Position Among the Stars

Speaking to one of IDFA’s wider concerns, she also decried what she saw as humanity’s increasing reluctance to contemplate matters religious or spiritual – an issue “as urgent as attending to climate change or the economic crisis”. And yet religious faith proved to be the theme of some of the most discussed films in IDFA’s feature-length competition.

Position Among the Stars (2010) was named Best Feature-Length Documentary and Best Dutch Documentary before heading on to Sundance. Following an Indonesian family divided by religious beliefs and besieged by globalisation and consumerism, it’s filmed in beautiful, highly elaborate camera moves – director Leonard Retel Helmrich’s now famous single-shot cinema – and dwells on the border between the observational and the contemplative. Its exquisite closing sequence, involving two elderly women out in a field at night, ‘among the stars’, captures that particular relation with time and temporality held by Helmrich’s elderly subjects, living at the crossroads where nature and tradition meet the rapidly advancing cultural modernity that has already swept up the younger members of the family.

Of the events available during my stay at IDFA, the highlight was Sam Green’s Utopia in Four Movements, a ‘live documentary’ that reached Amsterdam having premiered at Sundance. Leaving Amsterdam soon after Green’s performance, I was abruptly plunged into the dystopian: locked together with other tourists inside a small hotel near the place where protesters had been heading four days earlier to “scream for culture”, we witnessed a sudden spell of violence involving a large group of men shouting slogans that we did not understand and a massive number of policemen descending from cars and kicking these men with their batons. For the following 15 minutes, until the hotel receptionist allowed us to leave, we witnessed a saddening prelude to a football match between Amsterdam’s Ajax and Real Madrid.