A market in Mexico City in the summer of 1968. A middle-aged woman, wearing a string of pearls and fine earrings, is having a loud argument with a student in boots and a miniskirt.

“What in the world do those students want? They just want to stir up a fuss, that’s all! I’m certain they’re Communists – they must be to act like that!”

“Listen, señora,” the young student replies, “you’re going to have to explain what you mean, because what you’re saying is nonsense. What are you trying to insinuate?”

Gradually more and more people get drawn into the argument, until a large crowd has formed, vigorously debating. The original protagonists slip away.

In Mexico in 1968 the government controlled the newspapers, the radio, the television and the cinemas, so students in Mexico City, rebelling against the authorities in great numbers, had to become creative propagandists. Those studying graphic design created thousands of visually inventive posters, the aeronautical students designed balloons that would shower leaflets down on to crowds below, and students of the acting school – even middle-aged ones wearing pearls – would stage ‘happenings’ in public places: play-acted confrontations that encouraged people to talk about and debate the repression they were suffering under the one-party government of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which had ruled Mexico since 1929.

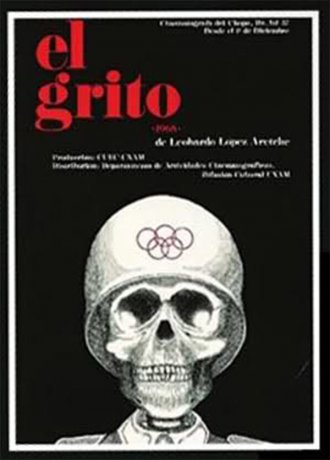

El Grito (1968)

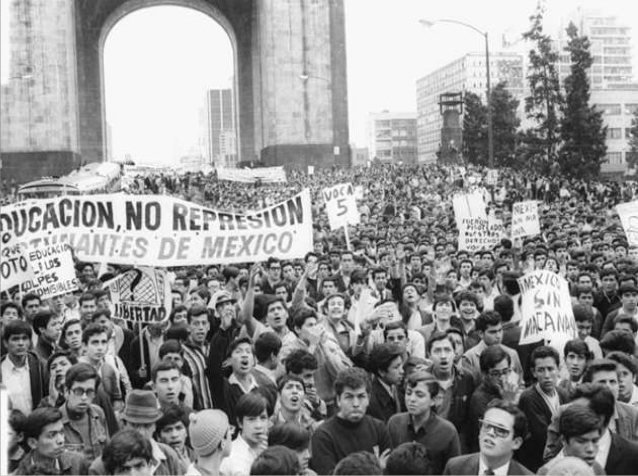

Most Europeans identify the events of 1968 with images of radical students throwing cobblestones in the streets of Paris. But the political instability in France was part of a larger a wave of unrest around the world – from Tunisia to Egypt, Brazil to Ethiopia – playing out differently in these individual countries depending on the particular conditions. A series of increasingly well-attended demonstrations organised by students erupted in Mexico City over the course of the summer of 1968 – at its height, as many as 600,000 people reportedly took to the streets of the city to support greater freedom for trade unionists, the press, transparent democratic processes and political dissent. Mexican novelist and intellectual Carlos Fuentes, writing a few years later, thought the complacent authorities had been caught off guard, and were especially worried as the Mexico Olympics approached, and the world’s attention turned towards the country. “Unaccustomed to dissent, the regime panicked,” Fuentes wrote. “It had no political answers to political challenges.”

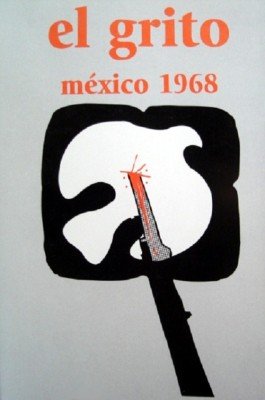

A protest pamphlet from 1968

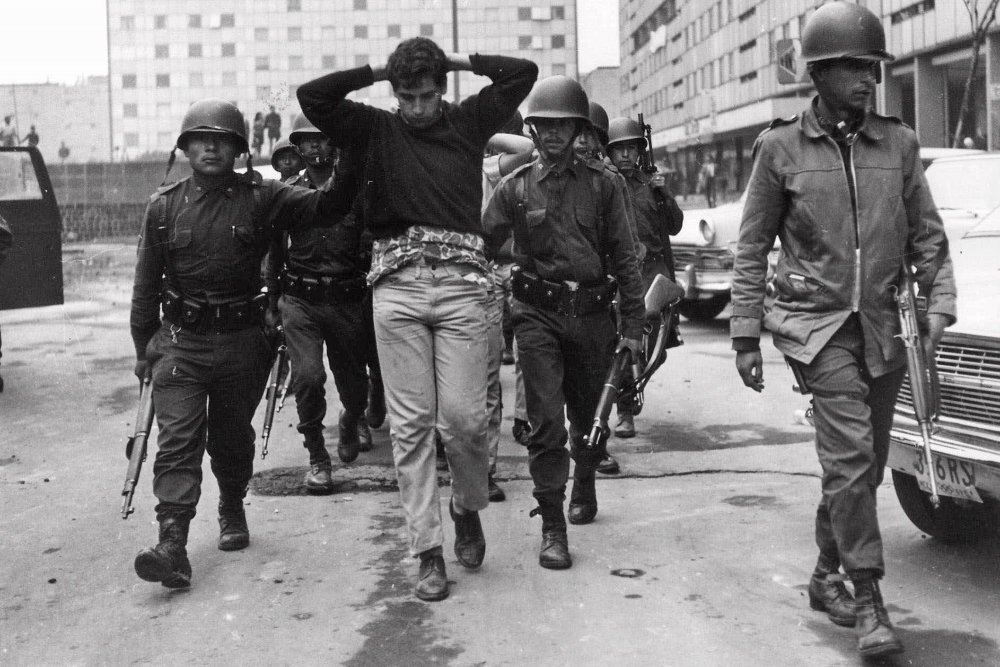

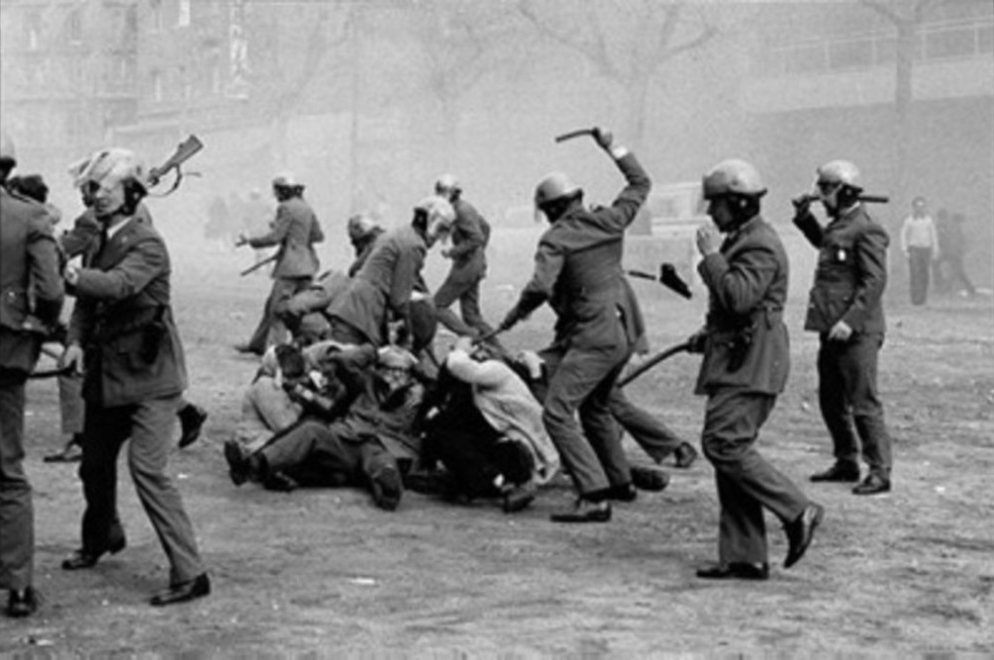

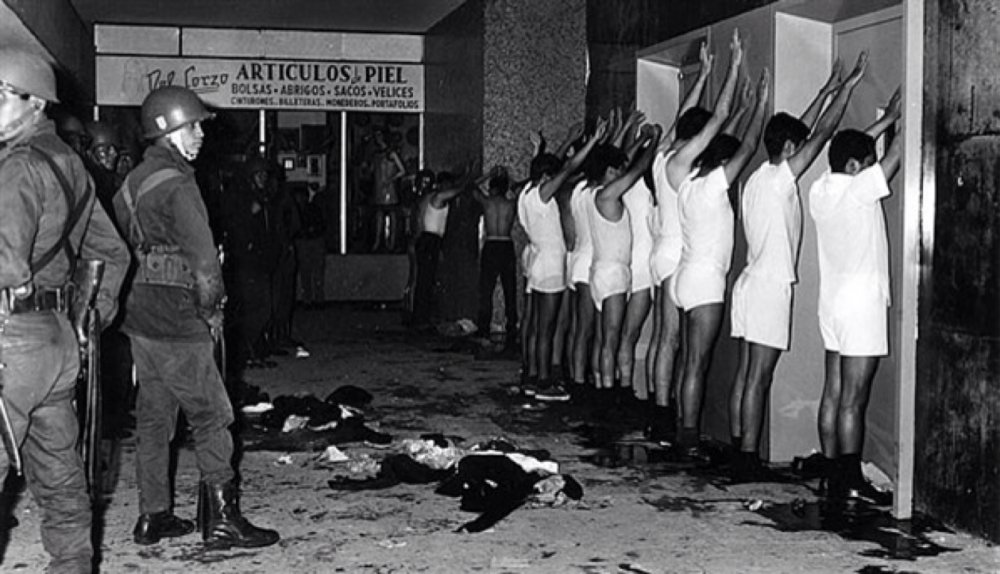

Increased repression followed. Soldiers occupied the university campuses, thousands were arrested and imprisoned by the government. Torture, beatings and shootings were common, and the nascent movement came to a violent and sudden end when soldiers and police opened fire on a public meeting on 2 October, killing up to 400 people and injuring many more, in the public square of a new housing development called Tlatelolco. “The night of Tlatelolco,” wrote the Mexican academic and activist Sergio Aguayo this month, “continues to be engraved not only on individual memories, but on our collective consciousness as well.”

*

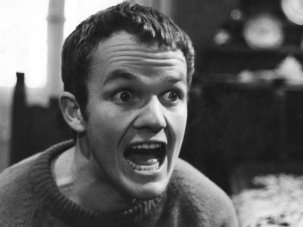

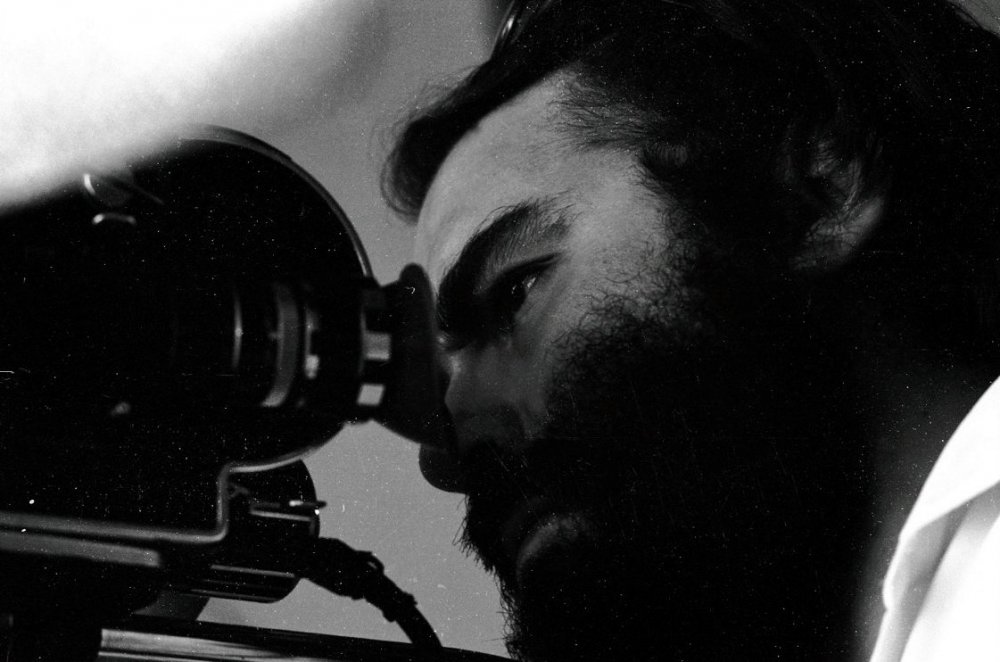

One of the people responsible for keeping the massacre in the collective consciousness was, at the time, an idealistic 26-year-old film student called Leobardo López Aretche. In the summer of 1968 he was a prominent fixture at demonstrations and meetings, often perched on top of buses and monuments, with long hair and a long beard, going through endless rolls of film with his 16mm camera. He led a group of film students dedicated to documenting ‘El Movimento’ (the Movement) as it grew from July onwards, and he also gained esteem within its bureaucracy, becoming a member of the senior organising committee known as CNH, as a representative of the film school (the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematograficos). He was soon widely known simply by the initials of the latter – Cuec.

Leobardo López Aretche

Credit: Federico Weingartshofer

In 1971 the famous Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska published a blistering work of oral history about the Tlatelolco massacre, a collage of voices in which the young Aretche makes a couple of brief appearances: once, at a tense meeting of CNH, Aretche passionately put forward a motion that, in response to the tanks and bayonets of the governments, the students should fight back “with flowers, with love and flowers”. He explained: “If they attack us, we’ll throw flowers at them, we’ll throw flowers at their tanks. Everybody will be watching from the windows of their buildings, from the hoods of their cars, from the roofs of the buses, from the housetops… If the soldiers are armed with rifles, we’ll be armed with love and bunches of flowers…”

The exuberant motion was, perhaps unfortunately for Mexican florists, voted down, and when the police invaded university campuses that summer, Arretche fought back not with flowers but with his camera. He drilled a hole in the boot of his car and climbed inside, secretly filming soldiers patrolling the streets while a friend cruised around with his headlamps off.

El Grito (1968)

Then, in October, he was there in the square at Tlatelolco, filming as the carnage unfolded. He survived, but was arrested on the spot and imprisoned for months. On his release, having only previously made short films during his studies, Aretche set to work on his first feature length documentary about the Movement, and about the massacre: El Grito (The Shout). Completed in 1969, the film was banned by the authorities, shown in secret throughout the 70s and 80s, and was only allowed to be broadcast on TV for the first time in 1998, once the PRI’s grip on power was waning (they were finally voted out when free and fair elections were held in 2000).

El Grito is frequently listed as one of the most important Mexican films, and the influential Mexican film critic Jorge Ayala Blanco called it “the most complete and coherent filmic testimony that exists of the Movement, seen from the inside and in contrast to the calumnies put out by the rest of the mass media.” If the end of that quote sounds a little overblown, it’s worth remembering the stranglehold that the PRI had on the media back then, and for years afterwards – the day after perhaps as many as 400 innocent people had been shot in a public square, almost every Mexican newspaper without fail reported the government’s line that student “sharpshooters” had fired on the authorities in Tlatelolco, and that just 27 people had been killed in the ensuing shoot-out. At the time Aretche was virtually the only filmmaker providing a real riposte to the government’s official history, at great personal risk.

A poster for El Grito

I saw El Grito for the first time earlier this year, a rare international screening at the Cinema du Réel festival in Paris. It’s an abrasive, declamatory film, especially to an outsider – it feels as though it were made in anger, and anguish, and belongs to a very specific time and place. There are long sequences of political speeches and narration written by the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, and over the course of two hours the film builds chronologically towards a brutal crescendo, made up of grainy footage, photographs and harrowing field recordings collaged together to evoke the horror of the massacre.

The most affecting parts of the film, though, are not the most dramatic – not the massacre, nor the strident monologues. They’re the candid reels that Aretche shot of students gathering and chatting, talking, flirting, fighting, planning, arguing and laughing, eyes occasionally flicking towards the camera self-consciously. They look remarkably young – many of those involved in the movement were not in their twenties like Aretche, or even at university, but still at secondary school. These ostensibly relaxed sequences are full of a kind of queasy foreboding, in the knowledge of what might have happened, a month or two later, to any of those young people who passed under Aretche’s lens.

*

“History is like a horror story,” says the narrator of Roberto Bolano’s novel Amulet, published in 1998. Bolano arrived in Mexico City from Chile in 1968 with his family, aged 14, and threw himself into the politics and social life of the city. Amulet is inspired by the true story of a woman who, caught in the toilets when armed soldiers suddenly invaded university campuses in 1968, remained there, locking herself in for two weeks, surviving on water from the sink, in fear for her life. “Tlatelolco,” she says in Bolano’s book, “may that name live for ever in our memory.” She calls the massacre an “open wound”.

An aerial shot of the Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco

Credit: Margari Pari

In the 60s Mexico City was awash with new arrivals, like Bolano’s family, from all over Latin America, drawn by a postwar economic boom and apparent political stability compared to other Latin American countries, some of which had been plagued by violence and repression since the 1930s. Between 1950 and 1970 the city’s population grew from three million to almost seven million.

The Tlatelolco housing complex, built in 1962 by the architect Mario Pani, a disciple of Le Corbusier, was meant to embody this new spirit of growth and optimistic modernity, replacing a rundown industrial neighbourhood in the north of the city with dozens of gleaming blocks, some as high as 22 storeys, housing thousands of families, with a wide open public square in the middle. Enclosed within the modern square was a newly restored Aztec ruin, and a Conquistador-era Catholic Church – meant to signify the different turbulent eras of Mexico’s history coming together in the present moment in perfect harmony. The utopian development was even chosen as the site, in 1967, for the signing of the Latin American Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

El Grito (1968)

But the economic boom also led to an expanded middle class, higher literacy, and a youthful and educated population who became increasingly unhappy with the PRI’s lack of democratic transparency, and its authoritarian methods. As the movement gained momentum over July and August, the government tried to bargain with its leaders on the CNH, but they insisted on open dialogue, rather than the backroom deals that had characterised Mexican politics until then.

As the movement wore on, arrests became more frequent – it was illegal to hand out anti-PRI leaflets, or to daub slogans on walls. One teenager was shot dead by police for painting anti-government graffiti. It’s clear from Poniatowska’s book that the students were caught off guard by this new level of brutality – many can only compare the scenes of cruelty and torture they witnessed, or suffered, to gangster films – and that when the massacre came it shocked the movement into silence. “I have the impression that people were taken completely by surprise,” said one foreign correspondent at the time, “and have remained more or less petrified.”

El Grito (1968)

The years after 1968 were hard for many who had been involved in the movement. The PRI were still in power and would be for decades to come. Luis Echeveria, the man believed by many to have ordered the massacre, became president and was feted for his liberalising reforms which relaxed laws surrounding freedom of expression and gave state funding to the cinema industry.

Meanwhile scores of students still languished in jail, including the charismatic leader Roberta Avendano Martinez, known as ‘Tita’, who spoke to Poniatowska about feeling left behind by the way the country was going after the massacre. “It’s as though the whole thing happened years ago… Many of my friends have gotten married and gone back to their home towns – now that there’s nothing left of the Movement; they’ve made new friends and have new interests, and I feel very far away from them now.” Another student tells her about “a tremendous feeling of helplessness, of defeat”.

*

It was during these listless years after the massacre and the collapse of the movement that Leobardo López Aretche killed himself, in July 1970, soon after finishing El Grito and some months into the production of his first feature fiction film.

El Grito (1968)

The horrific nature of the Tlatelolco killings was made worse by the fact that, as a policy, it seemed to achieved its aims – the student movement was crushed, hopelessness prevailed, and the PRI had consolidated its power. A key part of this was suppression of the idea that the massacre ever happened at all – the official death toll remained under 30. (The Guardian at the time reckoned that, “after careful investigation”, the figure was about 325.)

This culture of official secrecy gave projects like Aretche’s an urgency – information became a battleground. You can see this in El Grito itself, which focuses on the communicative aspects of protest – setting up sound-systems, designing, printing and distributing leaflets in their millions – as much as it does the more eye-catching moments of demonstrations and clashes with riot police. In the absence of any real dissent in the official media, “painted slogans, mimeographed handbills, and our lungs were our press”. The student movement’s biggest expense, above all else, was paper. “You own the radio stations and newspapers,” shouts one voice in El Grito. “All we have are loudspeakers and mimeographs.”

A poster for El Grito

The battle for information continued after Aretche’s death, into the 70s, galvanised by the silence surrounding the massacre – indeed some trace the landslide election this summer of the leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as Amlo, directly back to the events of 1968. The tragedy, according to Sergio Aguayo, birthed a new generation of “professors, journalists, activists, labour organisers, or professional politicians”, dedicated to continuing the values of the movement and “to reconstructing past events in order to convey them to subsequent generations”. A self-financed feature film, the first to deal with the massacre, appeared in 1989 – Jorge Fons’s Rojo Amanecer, which takes place within an apartment in the Tlatelolco building, where various people shelter as the massacre unfolds.

But the real reckoning with the event has perhaps come after the PRI lost power in 2000 – documents relating to the event have been declassified, an important exhibition about the massacre took place in Mexico City in 2015 at the Museo Memoria y Tolerancia, and newly restored 35mm copies of El Grito have been screened in Mexico City and internationally. It is a shame that Aretche didn’t live long enough to see El Grito still being shown, 50 years after he first started taking reels of students gathering in squares.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.