A family has lost its head. The text that serves as a formal prologue to Hereditary announces the passing of 78-year-old matriarch Ellen Taper Leigh in the home of her daughter Annie Graham, after a prolonged illness. “She will be missed,” are the words that close the obituary – but there is little evidence that Ellen’s estranged family really do miss her. Annie (Toni Collette, travelling convincingly through a range of nuanced emotions) delivers a tactful eulogy that not only stresses Ellen’s secrecy but is also clearly straining to keep hidden the difficulties of Ellen’s personality. Annie’s husband Steve (Gabriel Byrne) and teenage son Pete (Alex Wolff) seem barely to care – and if Pete’s 13-year-old sister Charlie (Milly Shapiro) was without question Ellen’s favourite, she is herself a strange, troubled child, too affectless to express any notion of loss.

USA 2018

Certificate 15 127m 15s

Director Ari Aster

Cast

Annie Graham Toni Collette

Peter Graham Alex Wolff

Charlie Graham Milly Shapiro

Joan Ann Dowd

Stephen Graham Gabriel Byrne

[2.00:1]

UK release date 15 June 2018

Distributor Entertainment Film Distributors

hereditarymovie.co.uk

► Trailer

Hereditary opens with a long, fluid take of three different but proximate houses, as Pawel Pogorzelski’s slow-spinning, sinuous cinematography first reveals a treehouse (also the film’s final image) seen across the garden through a window, then pulls back from the window to show an artist’s workroom within the house opposite, and finally pans over the workroom to a table bearing a scale model of the house (with the wall removed from the front to expose the elaborately crafted interior). As the camera moves closer to a bedroom in the model, and to a figurine lying in the minibed, we hear a knock, and – impossibly – Steve walks right in to wake Pete for Ellen’s funeral.

This uncanny trick of blurring a scale model with the larger reality is something that has been seen before in films with themes significantly parallel to Hereditary’s, whether the facsimile of the school in Nick Murphy’s The Awakening (2011), which similarly stages the burden of grief, the persistence of the dead and the seductiveness of delusion, or the display model of the labyrinth in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), which also pits child against unravelling adult. Yet in opening with this lifelike doll’s house, constructed by artist Annie to work – in microcosm – through her family’s long, tragic history and her own difficult relationship with Ellen, debut writer/director Ari Aster establishes two things: first, the uneasy sense, right from the start, that the Grahams are somebody else’s playthings, like the dolls that Charlie collects; and second, that this mood of play-box paranoia, introducing tension at the outset and from then on never once relenting, will be managed with the sort of painstaking attention to domestic minutiae that Annie herself brings to her art. In these layerings of houses within houses, and in the dreams within dreams (Annie’s, Pete’s) that will soon interpolate themselves into the narrative’s reality, Aster merges naturalism with unnerving allegory to present an increasingly hallucinatory family portrait in which the psychological is reified and the devil is in the details.

The strange graffiti etched into the Grahams’ wallpaper – and of course reproduced by Annie in miniature – can be recognised as the writing on the wall for a dysfunctional clan whose suppressed demons must eventually out. Still, Aster will take his time parcelling out all their tortuous secrets, compartmentalised within the bourgeois veneer of suburban life, or hidden in plain sight in boxes, lofts and images. Though primed to expect that Ellen’s legacy, genetic or otherwise, must come home to roost, viewers are kept in excruciating suspense as to what precise form it will take, as recurring motifs of fire and decapitation, dissociative identity disorder and ritual beleaguer the film’s structure in a campaign of confusion. Aster throws in a whole palette of haunted-house tropes (seances and spectres, creaky corridor and creepy attic, infestations of ants and flies) as much to confound as to clarify, given that we are being misdirected no less than the Grahams are being carefully manipulated.

The big reveal, when it comes, is played with a disarming literalness – but its unhinged irrationality also makes it an effective and affecting metaphor for a family’s inheritance of guilt, recrimination and madness. Aster’s artistry here is phenomenally assured, even classical, as he deftly mixes subgenres, while focusing more on his bewildered characters than on the horrors that either they or we can see (often as blurs or shadows). Hereditary might be regarded as a psychological or supernatural thriller, an insidious ghost story, a literal cult movie, or Rosemary’s Baby (1968) after the infant has come of age. On any view, it is a diabolically assured debut.

In the July 2018 issue

Interview: Grief encounter

Ari Aster’s Hereditary, a terrifying portrait of a family coming apart at the seams, channels the spirit of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. By Anna Bogutskaya.

-

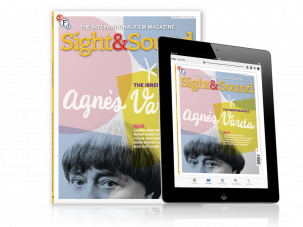

Sight & Sound: the July 2018 issue

The irrepressible Agnès Varda, Cannes 2018, Marco Bellocchio, Debra Granik, The Happy Prince, Budd Boetticher and more.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.