In Andrew Kötting’s melancholy, maverick film, a female voiceover from a 1970 BBC programme announces, crisply, “John Clare was a minor nature poet who went mad.”

United Kingdom 2015

Certificate 15 83m 26s

Director Andrew Kötting

With

goat impersonator/Ermine Street irregular Iain Sinclair

younger John Clare Toby Jones

older John Clare Freddie Jones

Dorothy Eden Kötting

Alan Moore, Simon Kövesi themselves

Mary Joyce MacGillivray

driver, drummer David Aylward

straw bear The Straw Bear [i.e. Andrew Kötting]

In Black & White and Colour

[1.78:1]

UK release date 2 October 2015

Distributor Soda Pictures

► Trailer

Clare studies have moved on considerably since then, with several biographies and editions of his work – which was first acclaimed and then relatively dismissed during his lifetime (1793-1864). He was a consummate outsider in the Romantic age – a working-class rural poet with a history of mental illness. A central event in his biography was his escape from an Essex asylum and four-day walk to Northamptonshire in search of his first great love, Mary. He also haunts the work of writer Iain Sinclair, who retraced Clare’s journey in his 2005 book Edge of the Orison, and does so again in Kötting’s film.

Kötting’s first full-length documentary, Gallivant (1996), travelled around the British coast, while his most recent, Swandown (2012), was also a collaboration with Sinclair. In By Our Selves, he imposes an early Victorian route on a largely transformed modern landscape. The project may seem kin to Patrick Keiller’s sombre eulogies for a disappearing world (London, Robinson in Space), though Kötting’s films are wilder and more questing.

By Our Selves (2015)

Clare’s account of his asylum escape in Journey out of Essex doesn’t romanticise this episode in his life: his feet were hobbled by the pace, he slept outdoors and ate grass by the roadside. By Our Selves shares his stubborn independence, which extends to the film’s funding – more than £20,000 was raised via a Kickstarter campaign – and to the determinedly lo-fi presentation. The title text is a scrawl, the camera wobbles alongside Toby Jones’s feet as he follows Clare’s route – a wavering lens for the poet’s wandering wits; a full-bearded soundman is often seen pacing beside Jones with his mop-head microphone.

Yet this is also a film of poised intent, shot in richly textured greyscale, often with exquisite detail: the dappled light, scrub and splinter on the forest floor; a wrinkled hand on dry bark. There are also quixotic touches, such as Jones’s image imposed on a medieval mural in Waltham Abbey, followed by a snatch of Evita’s Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.

Some commentators paint Clare’s plight as an index of change – a peasant poet protesting at and then maddened by agricultural exploitation. Kötting finds that the modern landscape is even more thoroughly policed, with security cameras clamped on the trees. Hedges have become pylons, lanes roundabouts; wayside inns give way to branches of Topshop; birdsong fades in the subdued whomp of a wind turbine. The poet records fractious encounters with villagers on carts, but Jones stands in a field as lorries thunder past, words drowned out by the cacophony beside a speed camera. When we hear one of Clare’s most resonant lines, “I long for scenes where man hath never trod,” those scenes seem further away than ever.

By Our Selves (2015)

I could watch Jones for hours: the baby-bird scruff of hair, his face like a paranoid turnip. He has a fascinating presence, all crumple. He has also played a surprising number of celebrated artists in extremity, working out their obsessions, whether Truman Capote in the film Infamous, Hitchcock (The Girl) and Hogarth (A Harlot’s Progress) on television, or J.M.W. Turner in The Painter on stage. In patched jacket, scuffed shoes, with a handkerchief knotted around his neck, is he portraying Clare, or following in his footsteps (a querulous villager on a mobility scooter scoffs, “That’s not John Clare!”)?

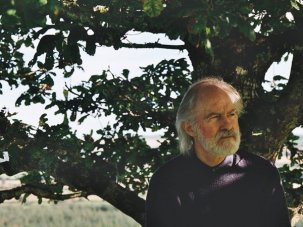

Jones remains silent in the film: appropriately, for a project about tottering in the footsteps of forebears, Clare’s words are read by Jones’s own father – the rubicund actor Freddie Jones, who himself played Clare in a 1970 episode of the BBC arts series Omnibus (glimpsed briefly here). Jones père’s accordion-creased tones are especially poignant, and Kötting retains his occasional vocal stumble. We see the actor close his eyes to recall Clare’s most forlorn poem, which begins, “I am – yet what I am none cares or knows,” adding, “I remember it in solitude.”

Sinclair walks out of curiosity, out of mischief, sometimes out of rage. In his books and journalism, his scepticism at the commodified landscape of south-east England can read like scorn – at history erased, but also at the little lives in neat homes in placid commuter belts. His oppositional voice can enliven but also alienate; especially when, as here, it seems to occupy a very male world (though his wife Anna is his walking companion in Edge of the Orison). The women in By Our Selves are marginal figures – the haunting Mary (the musician MacGillivray), singing and wafting her black shawl, and Kötting’s daughter Eden, shown in the grainy colour stock of home movies.

By Our Selves (2015)

The journey is periodically accompanied by folk-revival performers, self-conscious revenants from a lost age. Musicians in ribbons and animal masks hop along the roadside (they later bundle Jones into the back of their transit van, just as Clare’s family recaptured him); a ‘straw bear’ – a man encased in straw, an old Fenland custom to mark the start of the agricultural year – also tags along. (Kötting himself is inside the straw, according to the publicity notes.)

Sinclair takes to the road too, often wearing an uncanny white-goat mask. He doesn’t offer much context for Clare’s journey except in two extended fixed-camera interviews. He first meets the writer Alan Moore, who wrote about the journey out of Essex in Clare’s persona in the novel Voice of the Fire. A raffish, occult figure – wizard beard, multiple rings, stick – Moore describes the Northamptonshire flatlands as a “vision sump”, a place of “delusion and poetry”. He namechecks John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, the Lollards, Dusty Springfield and a cult of true believers awaiting Jesus in a house outside Bedford. He’s amiably scathing about Northampton, where he himself was born and where Clare spent almost the last 23 years of his life. “It’s difficult to get up the escape velocity,” he says. “Nobody ever gets out unless they’re sucked back in.”

Clare was an outsider – not necessarily through choice, but through vocation, sexuality, mental health. Kötting and Sinclair bear down on this to make him an oppositional figure, having Jones tap determinedly on a typewriter at the edge of a lake, or glare at the camera until it backs off. There’s a wilful eccentricity to all this, especially when Sinclair (still in his goat mask) interviews Simon Kövesi, of Oxford Brookes University, who is dressed as a boxer in homage to Clare’s own passion for prizefighting. Kötting’s pilgrim’s progress is most compelling when letting us inhabit Clare’s own disorientation, a prism for a lost soul in a constrained world.

In the November 2015 issue of Sight & Sound

Man on fire

The banal-sounding premises and mysterious motivations of Andrew Kötting’s films contain a world of beauty and genuis. By Stewart Lee.

-

Sight & Sound: the November 2015 issue

Guillermo del Toro’s gothic Crimson Peak, Andrei Tarkovsky’s path-forging screen poetry and Yorgos Lanthimos’s starry social...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.