Spike Lee’s third feature, Do the Right Thing, remains a genuine one-off. A vivid, unabashedly theatrical snapshot of one blisteringly hot day in the life of a multicultural Brooklyn block, it was an impassioned response to simmering racial tensions in New York City by its then 32-year-old auteur. From the superb performances by a vast ensemble cast to Ernest Dickerson’s searing cinematography; from its barbed, lyrical screenplay to the lushly versatile jazz score by the director’s father Bill Lee, it resounds as a singular artistic triumph.

Do the Right Thing is re-released in UK cinemas on 2 August 2019. It’s available to buy or rent on all home cinema formats including from BFI Player.

Despite an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay, Lee’s urgent dispatch was ignored by the Academy in the Best Picture category, which was won instead by the reassuringly tame race-relations drama Driving Miss Daisy. Yet Do the Right Thing’s influence looms large across popular culture on an international scale: it’s a clear forerunner for urban dramas like La Haine (1995) and City of God (2002); it’s been affectionately parodied on Sesame Street; and even the Obamas claim they saw it on their first date. Moreover, many of the issues it raises are still pertinent: Ryan Coogler’s recent Sundance-winning Fruitvale Station, for example, echoes Lee’s film in its focus on the police killing of a young black urban American male.

We asked a selection of contributors on both sides of the Atlantic to offer personal reflections on why Do The Right Thing continues to mean so much to them.

— Ashley Clark

Steve McQueen

Filmmaker

‘You Stepped On My Brand New White Air Jordans!’

The first time I saw Do the Right Thing, when it was over, I didn’t speak for a while. I was just trying to take it all in. It was a knockout – almost like being in a boxing ring. Sometimes it was brutal, and sometimes beautiful; an attack, done with style, anger and compassion. In terms of giving a snapshot of a New York community, the only thing that comes close are those films from the 30s and 40s like Angels with Dirty Faces.

It brings back great memories, but also painful ones, and that combination is so powerful. Great art has a resonance in the past, present and future, and Do the Right Thing is just that. When it came out, the echoes with the UK political situation were loud and clear. In England, there was police brutality and unemployment, and it resonated with me in a direct way. I love the bit when John Savage’s character – the white guy wearing the Larry Bird jersey, carrying his bicycle – steps on the new Air Jordans that Buggin’ Out is wearing, and this sparks a heated conversation about gentrifcation. It reminds me of what England was like at the time, and it also illustrated the importance of trainers back then!

There are many iconic moments: the to-camera ‘love and hate’ speech by Radio Raheem stands out, as does the conversation between pizza-shop owner Sal and his racist son Pino, who says he feels sick of being in the neighbourhood. Through the window of the pizzeria you can see the autistic character Smiley milling around, and the way Lee builds up the tension is amazing; it’s ingrained in my mind.

But my most powerful memory is right at the start: you see the Universal logo – the image of the world turning – and there’s this lazy saxophone melody over it [Lift Every Voice and Sing, the so-called Negro National Anthem]; it’s as though Universal’s logo becomes part of the fabric of the piece, and it feels like the setting for an old fable that’s been told and retold. There’s the 40 Acres and a Mule [Lee’s production company] symbol, and then we go into the stunning credit sequence with Rosie Perez dancing to Public Enemy’s Fight the Power. It’s just beautiful. I was knocked out before the film even started.

Chaz Ebert

Writer and broadcaster

John Turturro as Pino and Spike Lee as Mookie

My husband Roger and I had our first date in September 1989, but we didn’t discuss Do the Right Thing, even though it meant so much to him. He didn’t assume just because I was black that I wanted to discuss Spike’s movies. At some point we did talk about it, though, because it made an incredible impression on Roger – he even threatened never to go back to the Cannes Film Festival because it didn’t win a prize [it lost out to sex, lies and videotape for the Palme d’Or]. Spike wrote a letter to Roger that said, “Thanks for sticking up for me. I give you permission to go back to the Cannes Film Festival.”

One of the things Roger found so strong about the film was his feeling that Spike did a movie about race in America that didn’t take sides. Usually, such movies have an agenda. In 1989, from an African-American point of view, we were very excited to see the movie. Lee had burst on to the scene: this new voice to advocate for urban black Americans. We were also irritated because some social commentators said there was going to be this big race riot because of it. And we said: “Why would a movie start a race riot?” It was incomprehensible to us that people would think that way.

I also remember leaving the cinema after those two closing quotes on the screen, from Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Some people said, “Did you see the juxtaposition of those quotes? He had the Malcolm X one last – ‘I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defence, I call it intelligence’ – so does that mean he was advocating violence?” We said: “No, he had both on the screen to leave it up to you to decide which was the most valid for the state of race relations at the time.”

Penny Woolcock

Filmmaker and opera director

It’s one of my all-time favourites. It’s an extraordinary achievement because essentially it’s 24 hours of a very hot day, which culminates with a young black man being killed by the police – and yet it’s so funny and so humane. Every single character in it, except for possibly the policeman who kills Radio Raheem, is afforded some dimensions, so you understand where they’re coming from. One of my favourite scenes is when the Korean grocer stands up to the towering figure of Radio Raheem with his ghetto-blaster, and Raheem respects him for it, cuts him some slack.

It uses a light touch to say things that are quite difficult to say, and it never feels like you’re being preached to. For example, there are the three old black guys sat on the corner who are chewing the fat and complaining about how they’re not making money like the Korean shopkeeper. You feel for all the characters, including Sal, the guys on the corner, and Mookie [played by Spike Lee] with his slouchy walk, his refusal to hurry and his refusal to apologise for anything – he’s such a slacker. I rewatched it recently and it’s just as fresh and exciting as it always has been. It’s visually extraordinary and it has such energy. It starts and it’s like a rollercoaster that barrels along and keeps surprising you.

Destiny Ekaragha

Filmmaker

Today’s Forecast

I grew up on an estate in New Cross in London, but it didn’t feel like we were in the ‘ghetto’ – we were just a bunch of kids that would play out in the summer. For me, Do the Right Thing, which I first saw in the 90s in my early teens, captured exactly that feeling, with its colour and vibrant characters like Mister Señor Love Daddy in his budget radio station. One of my favourite lines ever is when he says, “Today’s weather is… HOT!” He ain’t messing around with degrees Fahrenheit or anything like that.

It remains so important because it touches on issues of race and class – and people’s perceptions of those things – like no other film before or after. It was the first film I saw which broke narrative and had people talking directly to camera. It was laying bare what different racial groups said about each other. It said: “Make no mistake, we are living amidst racism – it’s as thick as the humidity in the air.”

Today, there are people pretending that racism doesn’t exist, that we’re in a ‘post-racial’ era – but that’s the most stupid term I’ve ever heard. If people don’t acknowledge that racism is still here, then we’re going to go backwards. And that’s why Do the Right Thing resonates today: it uses open dialogue and conversation to bring these issues to the surface.

Göran Hugo Olsson

Filmmaker

Spike Lee as Mookie

When Do the Right Thing hit the screens in our local cinema in Stockholm, it changed us for ever. Having had my formative years in the punk era, it was natural for me to latch on to hip-hop when it emerged in the 1980s. Hip-hop and punk connected not only in their inherent social consciousness, but they both presented a 360-degree formula encompassing a new type of music, fashion, visual language and dance.

Do the Right Thing filled up the missing gap in hip-hop: film. And at the same time it singlehandedly took cinema into a new, fiercely contemporary phase. Do the Right Thing was the first film in my time that felt real. I’m sure for another generation it might have been Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle, but for me that moment arrived when Do the Right Thing told me: this is the way.

Brandon Harris

Academic and critic

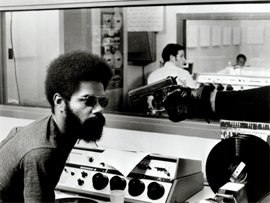

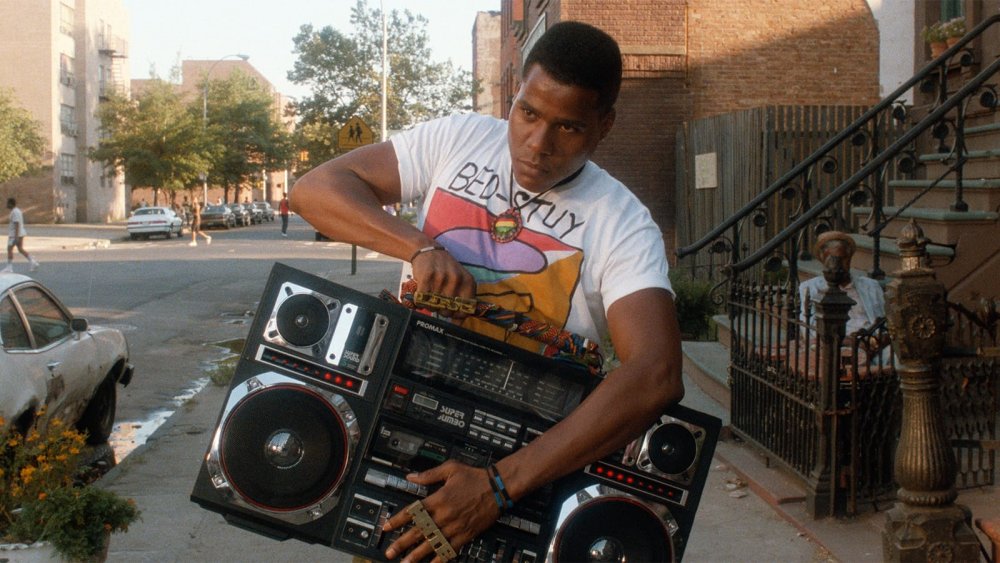

Bill Nunn as Radio Raheem

Although a Bedford- Stuyvesant street in Brooklyn has recently been [voted to be] renamed Do the Right Thing Way, the neighbourhood depicted in Lee’s film is long gone. Housing prices have risen, driving many working-class people out of the area; racial anomie has taken on more coded, insidious forms; and nobody wears Jackie Robinson jerseys or listens to Chuck D for the hell of it any more. Despite the still-relevant, seemingly ripped-from-the-headlines quality of the film’s climax – dead black body at the feet of culpable white cops – the dominant narrative of the space has changed.

In fact, the Bed-Stuy of that incendiary film may never really have existed. Was its kaleidoscopic ensemble – its representational melting pot – the reality of those central Brooklyn streets at the time? I’m not so sure any more. That particular slice of Bed-Stuy may not have been overrun by crack, poverty and disinvestment – to speak nothing of more common kinds of predatory policing than the death of Radio Raheem suggests – but to watch Lee’s operatic and invigorating film is to encounter their erasure.

Why did Lee choose to do this? You’d have to ask him, but I have some suspicion that given the film’s already strident racial politics, an accurate depiction of the inner-city streetlife of the era – which Lee tackled with greater verisimilitude in 1995’s Clockers – would have been a bridge too far for the studio, Universal.

Lyle Owerko

Photographer and author

Fight the Power

Visually speaking, Do the Right Thing remains a blast to the senses, from its heavy use of Dutch angles [in which the camera is tilted] to the extreme cropping of characters. The film captured the voices, collisions, friction and heat that went down on so many street corners in the larger New York canvas.

It drew upon real racial tension, but harnessed the power of hip-hop in a way few, if any, films had done previously. Using Public Enemy’s Fight the Power as a jump-off point, it engendered the opinionated nature of rap; the feeling of authority colliding with disaffected youth. The rap music, and the B-girl bop from Rosie Perez, helped to change style, dance and urban expression for a generation to come – it’s an attitude that still carries weight in the schoolyards and media of today.

Do the Right Thing truly established characterisations that people identified with in many ways, from the leaders to the agitators; the peacekeepers to victims. The most iconic character was Radio Raheem – he was a man with a method, who stood out from the pack with defiance and swagger. For better or worse, he became a true metaphor for a generation.

-

Sight & Sound: the September 2018 issue

Spike Lee: the BlacKkKlansman interview; the indomitable Joan Crawford; Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War; Mark Cousin’s on the drawings and...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.