The difference between the Civil Rights and the Black Power movements is one of geography as much as ideology, of regional radicalised realpolitik versus a more conceptualist and performative approach to the problem.

Black Power emerged in the north and west of America as ineluctably as desegregation had found traction in the American South. Civil rights forever transformed the way racial discrimination could be fought in all US courts, but Black Power changed the way black Americans perceived themselves. It turned every negative about being black into a positive and potentially revolutionary act. Civil Rights was concerned with racial equality; Black Power was focused on racial identity and visibility.

These philosophical tensions – between black-activist race thinkers who desired full citizenship and those who wanted to confront white supremacy wherever it reared its ugly head – had produced a Martin Luther King on the one hand and a Malcolm X on the other. The black America we have today is a hybrid of King’s pursuit of legal remedies to racism and Malcolm’s rage to amplify the voice of black American consciousness. Without King there’d be even fewer black students and professors at Harvard, Princeton and Yale; without Malcolm there’d be no Africana Studies programmes at any of those esteemed institutions. No King, no black executives on Wall Street; no Malcolm, no millionaire rappers or multi-billion-dollar global hip-hop industry built on their loud, proud, vive le black difference self-articulations.

Civil Rights expanded the literal physical space blacks could occupy in lily-white America, while Black Power extended the range of our metaphysical assault on the American racial imaginary. Civil Rights gave Don Cornelius the legal right to produce and own his nationally syndicated TV show, but Black Power ensured that show would be Soul Train.

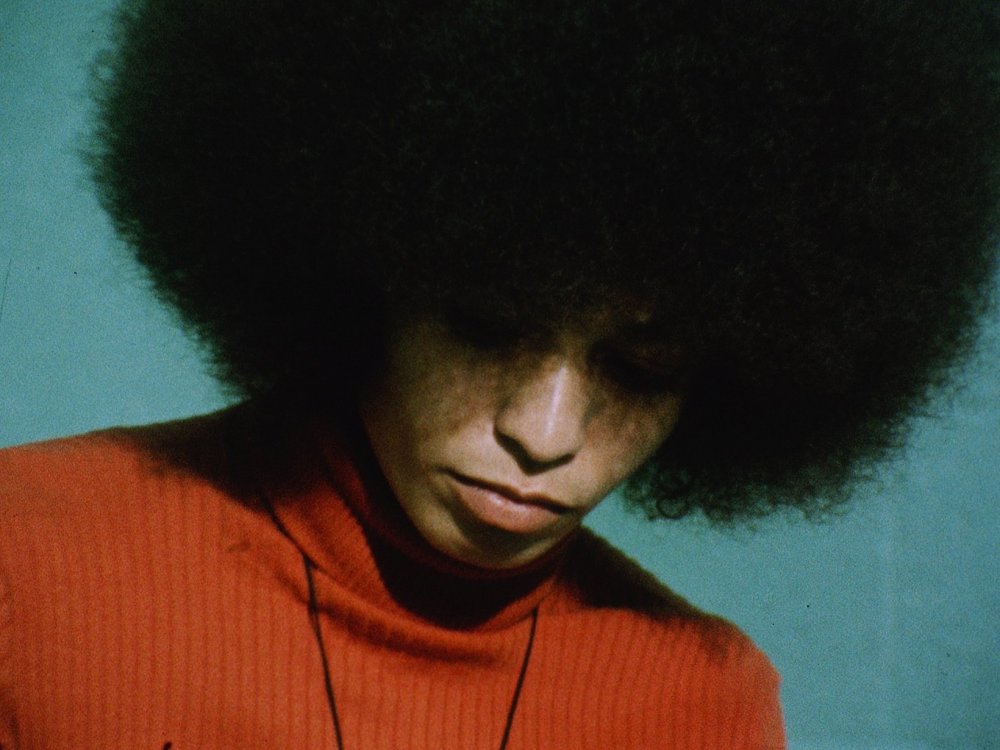

Angela Davis

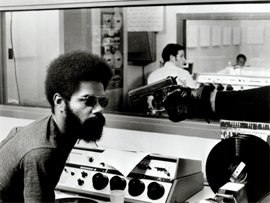

The Black Power Mixtape Remixed 1967-1975 is an exotic document of this turbulent, extremely violent transitional moment in American race history. Exotic because it’s the culmination of the near-decade an intrepid Swedish TV news team spent interviewing prominent Black American radicals of the day – Stokley Carmichael, Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, Elaine Brown and Angela Davis. All were dramatic, eloquent, charismatic figures of their time who, except for the still-active Davis, are today hardly household names to the average black American under 40.

Like Jimi Hendrix or Bob Dylan, they all seem incredibly well-prepared in their mid 20s to set the world aflame intellectually and dominate the media – but far less prepared than the Viet Cong or Fidel Castro to withstand the withering, brute and constitutionally illegal attacks directed at them and theirs by the US government, especially the FBI’s fascistic overlord J Edgar Hoover.

Time has not diminished their critiques of American power or racism, nor their undeniable star power – any of them and their radical histories could easily sustain a documentary or narrative feature film of its own. Mixtape captures most of them in the short period before they would be tried, convicted or exiled by Hoover’s stated and manically implemented obsession with preventing the “rise of another black prophet” after King.

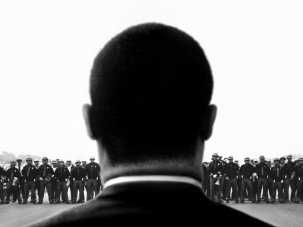

The footage of Carmichael and Davis is the most poignant and illuminating. Though the film doesn’t say so, it was Carmichael who brought the phrase ‘Black Power’ into vogue, famously goading King to give it airtime near the end of the two-week-long march to Selma, Alabama. The film demands that those who don’t know these figures investigate them afterwards for more background and context. On film the jocular Carmichael proves so at ease in his own skin that he could have given Sidney Poitier competition as a leading man, and challenged Bob Marley as a lyrical protest balladeer.

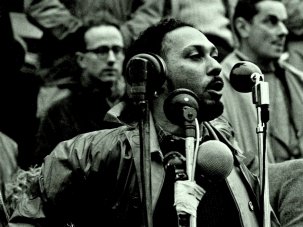

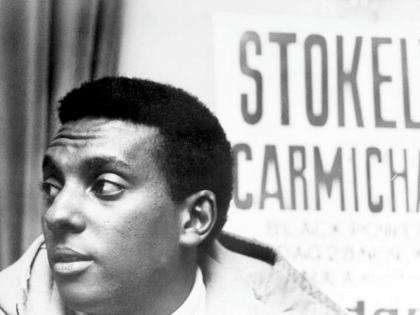

Stokley Carmichael

Carmichael invites himself to take over an interview the news crew had wrangled with his mother in the Chicago-projects apartment in which he was raised. He then patiently extracts from her the pained admission that his Trinidadian immigrant father, a skilled carpenter, was a lifelong victim of employment discrimination.

As noted by progressive hip-hop MC Talib Kweli in his voiceover, Carmichael emerges here as a “regular guy” who also happened to be a incendiary and mesmerising speaker – one still so provocative that Kweli recalls being accosted by FBI and TSA agents at an airport after 9/11 for merely listening to a 40-year-old Carmichael speech. Some may take Kweli’s intimation of wiretaps as conspiratorial and apocryphal, but no-one familiar with Hoover’s paranoia and surveillance of black progressives will be among them. (The biggest laugh in the film comes from Hoover’s claim that the most dangerous threat to the internal security of the United States was the Black Panther party’s free breakfast program. But Hoover was not joking.)

The progress of the film is also a tacit record of the Panther’s off-screen dismantling by Nixon and Hoover’s COINTELPRO conspiracy against black leadership. The Panther’s demise by exile, imprisonment and judicial malfeasance is presented at a glance, but the Panthers expended all their political capital on the campaigns to Free Huey Newton, Bobby Seale and Angela Davis.

Davis’s prison interview here offers the most astute and moving rationale for extreme black retaliation to American racial extremists. When asked to justify the advocacy of black violence, Davis recalls her childhood experience of her Birmingham, Alabama community being routinely bombed by Klansmen at the behest of notorious county sheriff Bull Connor. Davis recalls this motherfucker using local radio to promote and direct such violence on a weekly basis. The extreme close-up of her angry, watering eyes when she speaks of the discovery of four classmates’ body parts after the infamous 1963 Birmingham church bombing provides all the justification for retribution any rational person should need.

The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 (2011)

Davis also emerges as the figure from that time still alive, active and significant to her community today. Hip-hop MC and folksinger John Forte, who came to prominence in the mid 1990s with The Fugees, spent eight years in federal prison on drug-trafficking charges. He recalls how Davis’s advocacy for the abolition of the American prison system was a text he often shared with fellow prisoners.

We can assume the Swedish documentarists’ coverage and interest in black America ended in 1975, along with America’s war against Vietnam, once their gloomy focus had turned to the devastation high-grade heroin was wreaking on Harlem. The film’s final interview, with a cherubic woman barely out of her teens overcoming a former life of addiction and prostitution, captures the bleak promise left among the ruins of the movement.

International media wouldn’t return with much vigour to reporting on black America until hip-hop and the crack epidemic created a new generation of fiery progressives, and made urban America’s misery index appear again newsworthy enough to warrant the world stage.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.