from our February 2013 issue

In Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 Inglourious Basterds there is a scene in which Nazi soldiers play a kind of 20-questions guessing game, trying to identify famous figures. One has been dealt King Kong: “I visited America?” “Yes.” “When I arrived in America, was I displayed in chains?” “Yes.” “Am I the story of the negro in America?”

|

USA 2012 165m 11s Crew Cast Dolby Digital/Datasat/SDDS Distributor Sony Pictures Releasing |

It was a disquieting little sneak-attack undercutting the righteousness of the American cause in a movie set behind enemy lines, and it pointed towards Tarantino’s latest, Django Unchained – which is largely free of such surprises. Just as Inglourious Basterds corrected history with a Hitler-slaying fantasy of ‘Jewish vengeance’, so Django Unchained sets out to create a no-forgiveness fantasy of bloody black empowerment.

The title comes from Django, a 1966 spaghetti western starring Franco Nero, who makes a wholly egregious cameo here. With Django Unchained – which joins a lineage of countless name-alone ‘sequels’ – genre miscegenist Tarantino has hybridised spaghetti, where the only way to save civilisation is often to destroy it, with blaxploitation’s barrel-of-a-gun enfranchisement.

His Django harkens back to the post-Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song moment in American movies – a historically necessary moment – when all manner of pictures suddenly embodied the free-floating racial animus which had mostly been staved off with Stanley Kramer diplomacy when it appeared on screen before. It was a time when you might gape incredulously at James Mason using a black boy as a rheumatism-relieving footstool in 1975’s Mandingo; when there were films released with titles like The Legend of Nigger Charley and Run Nigger …Run; when shockumentarians Franco Prosperi and Gualtiero Jacopetti toured a recreated antebellum South in 1971’s Goodbye Uncle Tom.

After enumerating the abuses of white masters, Prosperi and Jacopetti ended their film with a cathartic bang of reprisal: Afro’d young men in Black Panthers leather lead an invasion into a sleeping white family’s bedroom where they slaughter the helpless occupants, dashing an infant’s head against the wall. Tarantino’s final purgative bloodbath – human bodies bursting like jam-filled confectioneries – does not go quite this far, though it does have Django using a shotgun to casually blow an unarmed woman through a doorway for comic effect, as if she’s being yanked offstage by a vaudeville hook.

The viewer has a long road ahead before arriving at this dubious reward. Django Unchained is the first film Tarantino has made without editor Sally Menke, who died in 2010 [obit]; does her absence explain its lagging pace? Swollen by Tarantino’s usual loquaciousness – there are so many monologue breaks it feels like a toastmasters’ meeting – Django Unchained stretches towards three hours of screen time and has a rambler’s tendency to repeat itself. At times this seems merely careless – Tarantino twice uses a fainting woman as a punchline – and at others it seems part of the master blueprint, as in the movie’s double-climax.

A doubling motif, you see, is at the centre of Django Unchained, which features two interracial duos: Jamie Foxx’s freedman Django and Christoph Waltz’s hitman Dr King Schultz are pitted against Leonardo DiCaprio’s master Calvin J. Candie and Samuel L. Jackson’s head butler Stephen – certainly the more psychologically fascinating of the two pairs. Under Stephen’s snowy mane lie the real brains at Candie’s plantation ‘Candyland’, where he has free rein to talk back to his putative master. Candie is louche and irresponsible gentry, nursing an unseemly obsession with his sister, and DiCaprio visibly enjoys himself in the role, slurping a frou-frou coconut drink and hollering things like, “What’s the point of having a nigger that speaks German if you can’t wheel her out when you have a German guest?”

That word “nigger” pops up a lot, with dozens of different inflections – barked by Jackson, evilly drawled by Don Johnson’s ‘Big Daddy’, mouthed with sweet-toothed relish by DiCaprio. You may recall that, shortly after the release of Jackie Brown (1997), Tarantino caught fire from Spike Lee for his generous use of the word in that film’s script. He was defended then by none other than Jackson – and Jackson’s Uncle Tom character here seems to parody the role he’s played in Tarantino’s career. Stephen is the true antagonist of the piece as Django is the true hero.

One sees how this structuring duality worked on the page – but the movie disappears in the canyon between intention and execution. Waltz, justly made a star by Basterds, again pinches Tarantino’s monologues with the fluting inflections of his native Viennese German, but his Dr Schultz is most often merely a precious, prim kook. He has no particular rapport with Foxx, whose journey from servant to master of his own destiny is conveyed in various shades of stolidity. The key scene, in which Django wriggles out of captivity by feeding his jailers a line of jive – in Tarantino’s world, talk is power – is among the movie’s worst.

All this is not to say that Tarantino doesn’t have the right today to address history’s rankling grievances, but what’s sorely missing in Django Unchained is any sense of vital engagement with history – that, and vitality itself. As Django betrays such cooing pleasure at cartoon violence directed against whites, it’s hard to take its outrage at hot boxing and unleashed dog attacks against slaves seriously – in Basterds, Tarantino at least knew that depicting Auschwitz was beyond his range. The horror that Django Unchained expresses isn’t of slavery, finally, but of a filmmaker attempting historical tragedy while shackled by his own supercilious persona.

In the February 2013 issue of Sight & Sound

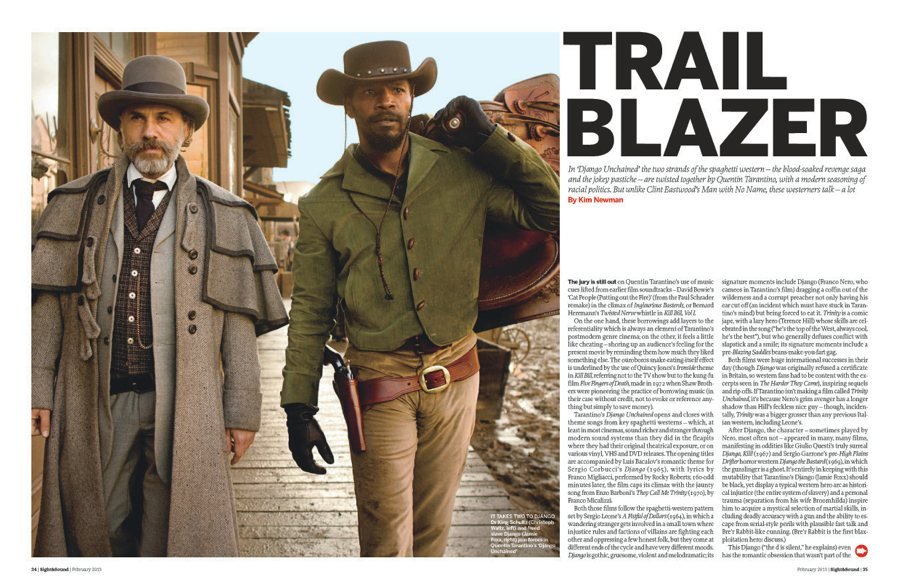

Trail blazer

In Django Unchained, Quentin Tarantino addresses the vexed subject of American slavery – spaghetti-western style. By Kim Newman.

+ Going back to my roots

Tim Lucas on the diverse cinematic roots of Django Unchained.

-

Sight & Sound: the February 2013 issue

Tarantino’s Django Unchained, Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty, Spielberg’s Lincoln and much more.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.