Originally published as The Legacy of Pauline Kael in our July 2019 issue

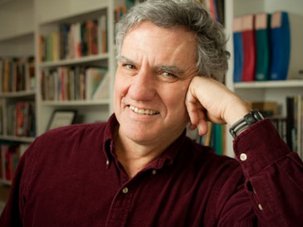

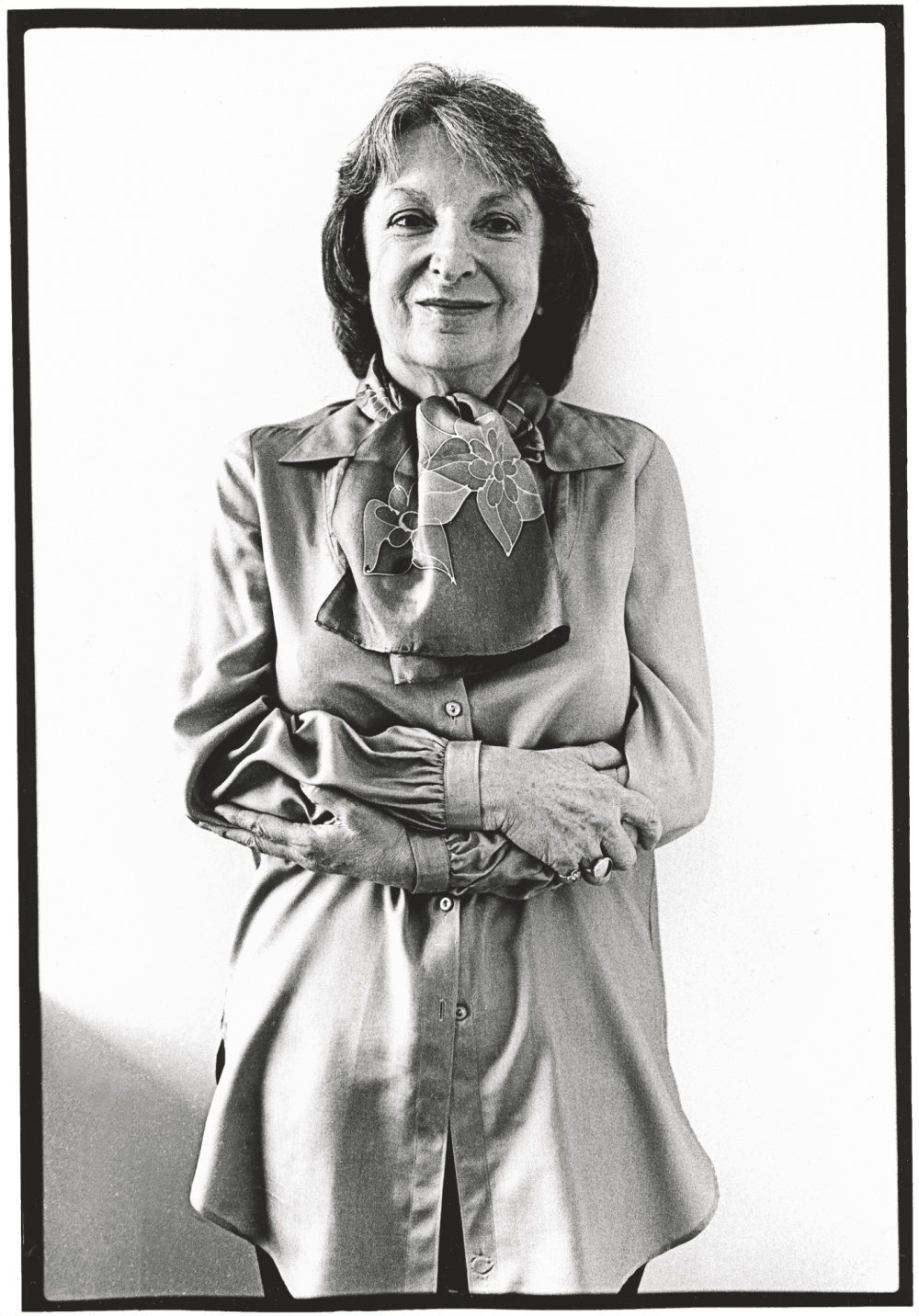

Pauline Kael

Credit: © Getty Images

Bored today? Feel a restless urge to start a fight? There are a million ways to do that on social media, but if you want to confine the combatants to film lovers, just mention Pauline Kael. Like magic, her fans and her detractors begin to circle. Aux barricades! This works, by the way, even if all you do is quote her. The fight comes gratis, like a dessert you didn’t order but are somehow obliged to eat.

Kael’s centenary was on 19 June 2019. She published I Lost It at the Movies in 1965, and her landmark review of Bonnie and Clyde, which helped revive the movie’s box-office fortunes and led to her job at the New Yorker, ran in October 1967. Film criticism is a frustratingly ephemeral calling, and few of its practitioners will be read as long as the movies they reviewed are watched. Not only is Kael still read, she still inspires passion.

She wrote a number of memorable pieces earlier in her career, notably Circles and Squares, an attack on what she saw as the absurdities of the auteur theory. It made quite a stir and permanently alienated Andrew Sarris and a number of other critics, foreshadowing the numerous enemies she would continue to make both inside and outside the industry.

Other notable moments in Early Kael included her passionate appreciations of Kurosawa Akira’s Yojimbo (1961) and Satyajit Ray’s Devi (1960), as well as her setting fire to The Sound of Music (1965) – “We have been turned into emotional and aesthetic imbeciles when we hear ourselves humming the sickly, goody-goody songs” – which may or may not have gotten Kael fired from McCall’s magazine. (Her editor later claimed it wasn’t the pan of The Sound of Music so much as that Kael also disliked Lawrence of Arabia, 1962; The Pawnbroker, 1964; A Hard Day’s Night, 1964; and Doctor Zhivago, 1965).

Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music

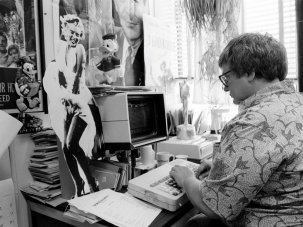

Kael’s greatest era as a critic runs from her hiring by the New Yorker in 1968 to her departure for an abortive stint as a consultant to Paramount Pictures in 1979. That this stretch coincides with an astounding burst of filmmaking creativity – whether you call it New Hollywood, the American New Wave, or just the 70s – is often portrayed as a stroke of luck; Kael occasionally said as much herself.

The truth is that great film critics make their own timing. They are sharply attuned to whatever the culture is reflecting, fomenting or ignoring. Otis Ferguson had the extraordinary cinema of the 1930s, and approached it with the same seriousness that he approached jazz, an attitude that set him apart. James Agee was himself more left-wing, more nostalgic and less patriotic than his key era, the 1940s, but he knew it, and that arrhythmic non-belonging made his writing all the more interesting.

During the 70s, Kael shared her New Yorker role with the coolly intelligent Penelope Gilliatt, swapping perches every six months and giving readers stylistic whiplash. Gilliatt was a restrained, elegant writer whose career was tragically undone by alcoholism and a plagiarism scandal. As for Kael, by all accounts, half a year of pay wasn’t enough to keep the lights on. Compiling and promoting her review collections and giving lectures kept her busy in her off-season, though she regretted losing the chance to review some movies when Gilliatt was on.

Kael’s attitude as a critic was one of excitement, of restless yearning for pleasure. Lurking even behind her stiletto-flick insults (Clint Eastwood “isn’t an actor, so one could hardly call him a bad actor. He’d have to do something before we could consider him bad at it”) and sighs of boredom (1970’s Song of Norway “brings back clichés you didn’t know you knew”) is a conviction that movies can thrill all the senses like no other art. As she might have put it – second person being one of her trademarks, like it or not – you can’t approach Altman, Allen, Scorsese, Spielberg, Coppola and De Palma (or Truffaut, Godard, Kurosawa, and Fellini) with the detached cocktail-party air of a critic like Brendan Gill. You have to give yourself over to them. Kael predicted this herself when she wrote about Bonnie and Clyde: “Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours – not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours.”

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde

“Reading her,” wrote Roger Ebert, “was like running into her right after a movie and having her start in on you.” Before Kael came along, the movie reviews in the back of the New Yorker were kept to a polite length encompassing a few paragraphs. Once she was there, however, hundreds of words became thousands. She liked to see movies with a proper audience, and her reviews usually ran well after a movie’s opening, a luxury that we denizens of the hurry-hurry internet area can only marvel at. Even if the film was one she mostly didn’t like, she wanted to ferret out the pieces worth savouring, as when she talks of Barbra Streisand and Louis Armstrong’s duet in the mostly dire Hello, Dolly! (1969): “There they are – immortals – and the ‘wow-wow-wow’ scat sounds that come out of her throat are cries of relief from the restraints of the dumb, unsophisticated show and all those tight, square chorus sounds.”

For a good movie somewhat short of a masterpiece, like Alan Pakula’s Klute (1971), Kael loved to spend a lot of time examining the part or parts that reached the level of art; in this case, Jane Fonda’s performance: “She has somehow got to a plane of acting at which even the closest closeup never reveals a false thought and, seen on the movie streets a block away, she’s Bree, not Jane Fonda, walking toward us.” And for a movie she did consider a masterpiece, such as Truffaut’s The Story of Adele H. (1975), Kael didn’t just watch, she basked in it: “Adele’s love isn’t corrupted by sanity; she’s a great crazy. She carries her love to the point where it consumes everything else in her life, and when she goes mad, it doesn’t represent the disintegration of her personality; it is, rather, the final integration.”

Donald Sutherland and Jane Fonda in Klute

Kael’s short time in Hollywood took a lot out of her, for reasons she explained well in the still-relevant essay Why Are Movies So Bad? or, The Numbers. She went full-time at the New Yorker just as the adventurousness that had animated American moviemaking began to lose force, or at least studio funding. If her writing sometimes seems less vigorous in this period, that’s partly because the movies were, too. When something exciting came along, Kael remained unforgettable, as in this review of Casualties of War (1989), which she considered the best of the late-80s cycle of Vietnam War movies. In many ways, it is peak Kael, with everything that irritates those who dislike her (that “we”) and everything that I admire: a gut-level intensity of response that offers more of what it’s like to watch Casualties of War than any other critic ever could:

“We in the audience are put in the man’s position: we’re made to feel the awfulness of being ineffectual. This lifelike defeat is central to the movie. (One hot day on my first trip to New York City, I walked past a group of men on a tenement stoop. One of them, in a sweaty sleeveless T-shirt, stood shouting at a screaming, weeping little boy perhaps eighteen months old. The man must have caught a glimpse of my stricken face, because he called out, ‘You don’t like it, lady? Then how do you like this?’ And he picked up a bottle of pink soda pop from the sidewalk and poured it on the baby’s head. Wailing sounds, much louder than before, followed me down the street.)”

Credit: Copyright Getty Images

“Her words may have been vernacular,” the critic Michael Sragow wrote, “but they’re elegantly honed to fit a mood and a conversational flow. That’s why her prose is almost as hard to excerpt in brief as dramatic dialogue.” Kael was known for reading her columns out loud before publication, checking for anything awkward.

She was known for other things, too, such as cultivating friendships with like-minded critics, Sragow among them, and for supposedly never seeing a movie twice, although she may have needed to do that less than others. In Rob Garver’s recent film, What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael, critic David Edelstein talks about watching the recut Touch of Evil (1958) with her, and being astonished by Kael’s ability to pinpoint every change from the version she had seen many years before. (Edelstein was often cited as one of Kael’s acolytes, nicknamed the Paulettes, a name he rejects: “I’m a Paulinista.”)

This self-taught, college-degree-lacking daughter of a chicken farmer wrote criticism by the brash authority she invested in herself. That has always got under people’s skin, no one more so than Renata Adler, who wrote a now-legendary pan of Kael’s 1980 collection When the Lights Go Down for the New York Review of Books:

“She has, in principle, four things she likes: frissons of horror; physical violence depicted in explicit detail; sex scenes, so long as they have an ingredient of cruelty and involve partners who know each other either casually or under perverse circumstances; and fantasies of invasion by, or subjugation of or by, apes, pods, teens, bodysnatchers, and extraterrestrials. Whether or not one shares these predilections – and whether they are in fact more than four, or only one – they do not really lend themselves to critical discussion.”

It was a memorable moment in the history of Kael-hating, buttressed by truths such as the numerous 1970s movies that do indeed have an abundance of horror, violence, casual sex and paranoid invasion fantasies, although Adler fails to convince me that’s a bad thing. But the indictment loses considerable force if you read A Year in the Dark, a review collection from Adler’s brief stint at the New York Times.

In 1968, Kael was loving Planet of the Apes and Rosemary’s Baby and Barbarella, and Adler was not: “In all of 1968, Hollywood produced scarcely any movies of any value,” she lamented. Adler approached movies as though weeding a garden, and each review is overgrown with her sense that film is barely worthy of her prose: “…A lot of the mystique of the ‘visual’ seems to me silly and obscurantist.” Adler was, in short, throwing down for the genteel school of New Yorker criticism that Kael had merrily obliterated, and indeed, after the hullabaloo of the Kael pan subsided, Adler’s next work to get the same level of attention would be Gone (1999), an extended lament for the end of William Shawn’s New Yorker.

It’s odd, considering the fame that New York Review of Books piece continues to soak up, that when you return to When the Lights Go Down, you find it includes The Man from Dream City, Kael’s tribute to Cary Grant: not only one of her best essays, but an astute look at exactly what actors of the Hollywood Golden Age were doing on screen. “Now the excess energy was pared away,” she wrote about Grant in his post-war thrillers; “his performances were simple and understated and seamlessly smooth. In Charade, he gives an amazingly calm performance; he knows how much his presence does for him and how little he needs to do.”

Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn in Charade

Kael will always be controversial, which will of course help keep her name alive – new generations of cinephiles will continue to rise up against her dislike of Badlands (1973). “Those of us who love her work and continue to be inspired by it are never going to have our minds changed by some Rotten Tomatoes-esque right/wrong binary reexamination of her taste,” wrote critic Jason Bailey on Twitter. “It’s the snap of her style, the energy of her prose, and idiosyncrasies of her taste that I hold dear.”

That very idiosyncrasy can make it hard to cite Kael as a role model, as does our fractured media landscape that makes it nearly impossible for a critic to aspire to her kind of fame. And in any case, she was seldom explicitly feminist. Stephanie Zacharek, film critic for Time magazine and a friend of Kael, told me, “I never looked at Pauline and said, ‘Wow, a woman can do this sort of thing, maybe I can too.’ It was more a subtext: her very existence meant I never needed to question what a woman ‘could’ do, so I never did.”

But Kael remains a significant inspiration for many women film writers, including me, through her barrelling prose, her enduring influence, and above all her fierceness. My favourite part of Brian Kellow’s 2011 biography was the story of Kael’s visit to a hardware store in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where she lived:

“It happened to be Mother’s Day, and the proprietor gave her a gift, adding in a condescending tone, ‘Because you look like you’re a mother or a grandmother.’ ‘Fuck you, Charlie,’ Pauline replied. ‘Do you know I’ve written ten books?’”

More Pauline Kael in the July 2019 issue of Sight & Sound

Mission critical

On 25 July 1982, at London’s National Film Theatre, Pauline Kael invited questions from the audience. In an edited selection from a previously unpublished transcript of the event, she explains why good films make her a better writer.

→ Buy a print issue

→ Access the digital edition

→

Pauline Kael in our archive

Is there a cure for film criticism? (in our Spring 1962 issue)

Some unhappy thoughts on Siegfried Kracauer’s Nature of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. By Pauline Kael.

Fantasies of the art house audience (in our Winter 1961-62 issue)

By Pauline Kael.

Morality plays – right and left (in our December 1954 issue)

By Pauline Kael.

Citizen Kael (in our June 1991 issue)

Funny, smart, a true cultural democrat. Tom Carson’s verdict on Pauline Kael as she retires as film critic of The New Yorker.

Pauline Kael obituary (in our October 2001 issue)

By Peter Matthews.

→

-

Sight & Sound: the July 2019 issue

Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die and the best of Cannes; the Golden Age of Mexican cinema; Andrew Bujalski’s Support the Girls; and...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.