Harry Dean Stanton generally gave the impression he’d rather be someplace else, alone. That was one of the things that made him different from most movie actors (let alone, a ‘star’). He was pissed off with the world, unimpressed with himself, and he didn’t care to hide it. It amused him, rather.

Disillusionment carries with it at least the ashes of enchantment, and no matter how tough his bark, or how tightly his thin lips sneered around another smoke, Harry Dean could never entirely extinguish a forlorn smile, the promise of romance buried behind his eyes. He’d give you that blank, flat look, but then he’d pick up a guitar and show you his heart, still breaking.

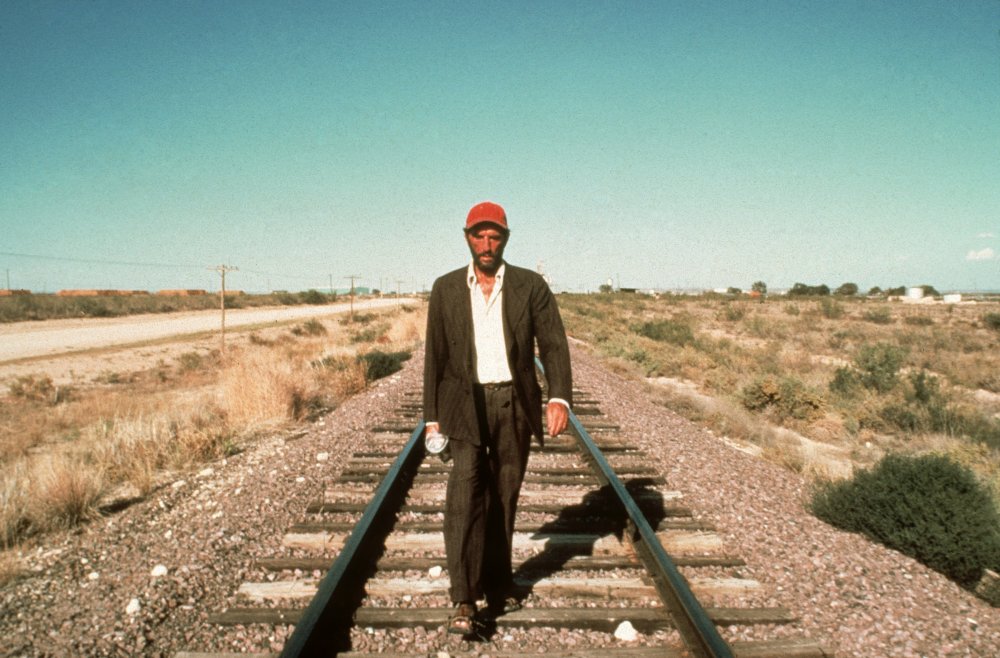

Is that Harry Dean, or Travis from Paris, Texas? You can’t slip a cigarette paper between them, which is why this seems to me one of the indelible, singular performances in the American cinema, an unvarnished and achingly vulnerable portrait of a dead man walking, lost in the wilderness, little by little coaxed back to life and attempting to restore some of the damage he’s done. Wim Wenders has said the actor doubted himself, that he didn’t know if he was strong enough to carry an entire movie on his shoulders. That fear is crucial to the film, the key to its emotional reach.

Harry Dean Stanton in Ride with Whirwind (1966)

Stanton worked a lot, and for a long time. The IMDb lists 199 credits, including a bit part in Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man as far back as 1956. As Dean Stanton he was an all-purpose cowpoke and saddle tramp in Gunsmoke, in Rawhide, Bonanza, The Rifleman, The Lawless Years, until his lifelong buddy Jack Nicholson threw him a bone and cast him as Blind Dick Reilly in Ride the Whirlwind (1966). “He’s got a hat and an eye-patch, but I don’t want you to do anything,” Jack said, advice Harry Dean took to heart. Director Monte Hellman liked what he did or didn’t do, and cast him again, as a hitchhiker who puts the moves on Warren Oates in Two Lane Blacktop (1971), and again in Cockfighter (1974).

Sideman to Warren Oates: Harry Dean’s lot in life. But at the same time he was living and partying with Nicholson, sitting in at the Troubadour with Kris Kristofferson and the band (“He liked Mexican songs,” Kristofferson remembered).

You can count the leading roles on the ring finger of one hand… well, almost. There was a documentary five years ago, Sophie Huber’s Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction, in which he grudgingly played along with her probing, but not too far (“No lines is better: Silence”) but sang freely instead, and now, right at the end, there is a Lucky, finally another lead, at 90, a seriocomic self-portrait of an independent son-of-a-gun coming to the end of the tunnel, and a fitting swansong for a man who ran away from success but found it anyway.

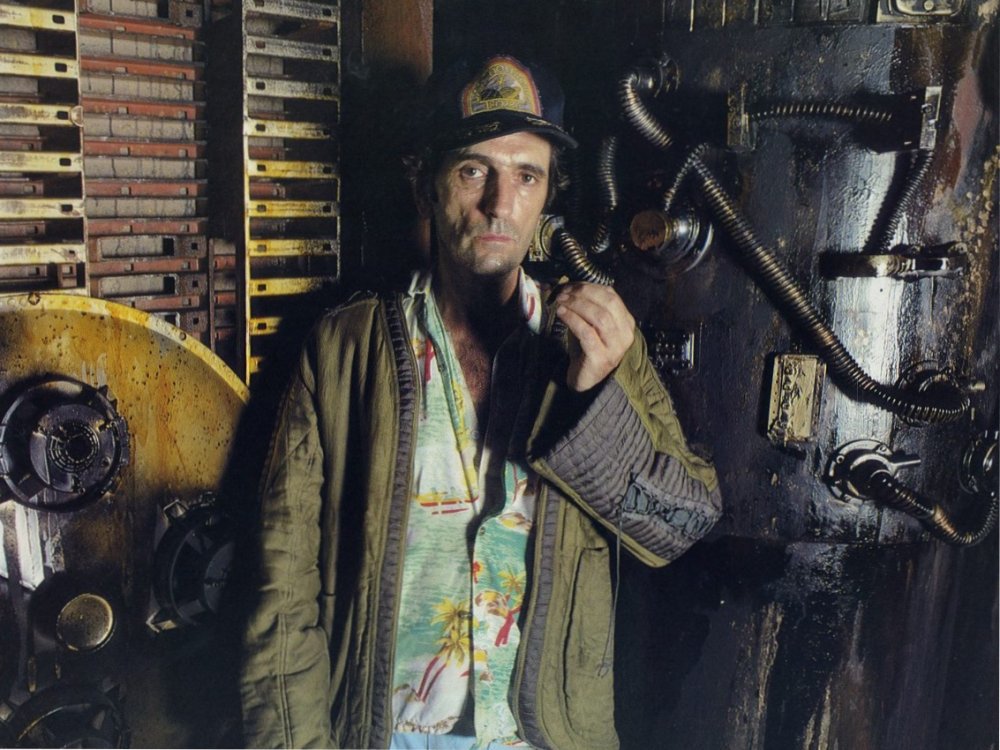

Wired and worrisome: Harry Dean Stanton in Repo Man (1984)

Back in the day no one knew his name. But when Harry Dean became cult-famous, in the mid-80s, it was possible to look back at the unruly, rough-’n’-tumble down-’n’-dirty glory days of 1970s New American Cinema and believe that he was in fact ubiquitous. There was that vignette singing the gospel tune Just a Closer Walk with Thee in Cool Hand Luke, and then he was a different Luke, one of the apostles, shooting chickens in Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid with Kristofferson and Dylan.

Back with Oates, he was Homer van Meter, gunned down in a fur coat in John Milius’s Dillinger (“Godammit! Things ain’t working out for me today.”). In 1975 he was in both Rancho Deluxe and Rafferty and the Gold Dust Twins for Frank Perry and Dick Richards respectively. Thomas McGuane put him in 92 in the Shade (Oates, again!), and Arthur Penn up alongside Nicholson and Brando in The Missouri Breaks, hoping perhaps to ground them. Look closely, he’s even in The Godfather Part II (“Star of Godfather 2 Dies”, some headlines claimed last week), a rare movie from the era in which he failed to smuggle in his guitar.

Smoking up the Nostromo: Harry Dean Stanton in Alien (1979)

It’s hard to imagine half of these films getting made at any other time in Hollywood history, but this cocktail of grubby realism, genre revisionism, loserville chic and still a dash of cha-cha-cha played its part in cementing Harry Dean’s persona. Like Nicholson his cynicism seemed hard-come-by, but like Oates he kept himself to himself and just got on with the job. This was a generation that knew hard times and never bought into the idea that the Boom would last (Stanton was born in 1926 in Kentucky, lived through the Great Depression, and served in the Navy at the Battle of Okinawa before he became an actor).

In his 50s, Stanton came into his own. The bits became genuine character parts, and people started to take notice of this skinny, ornery, prematurely grizzled cat with the weak chin, gaunt face and rueful eyes. He serenaded Dustin Hoffman in Ulu Grosbard’s Straight Time, smoked up the Nostromo in Alien (searching out Jones in a Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap), fathered Molly Ringwald in Pretty in Pink, and, best of all, he incensed Brad Dourif as the blind evangelical preacher, Asa Hawkes, in John Huston’s extraordinary Wise Blood.

David Lynch loved him: Harry Dean Stanton in Wild at Heart (1986)

He worked with Coppola again, revealing an under-appreciated comic flair as Freddy Forrest’s buddy Moe in One from the Heart; with Tavernier (Death Watch); Milius again (Red Dawn); John Carpenter twice (Brain in Escape from New York, the cop in Christine); with Altman (on another Sam Shepard piece, Fool for Love); Scorsese (Saul in The Last Temptation of Christ); and with David Lynch repeatedly (Wild at Heart; Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me; The Straight Story; Inland Empire; Twin Peaks). When Sean Penn or Nic Cage or Bob Dylan decided they wanted to direct, they called in Harry Dean. “Everyone loved him,” Lynch said last week. “And with good reason.”

There were forgettable and forgotten films too, of course, more as time went by and it seemed nobody remembered how to make them, or why… but as Roger Ebert wrote, “No movie featuring Harry Dean Stanton can be altogether bad.”

Paris, Texas (1984)

Two were altogether great: the one-two hit of Repo Man and Paris, Texas, both in 1984. The former is an inspired blast of anarchic, pure punk energy from Alex Cox, and features Stanton’s juiciest supporting role as the speed-snorting, wired and worrisome mentor to Emilio Estevez’s teen screw-up: “Look at those assholes. Ordinary fucking people. I hate ’em.”

Travis was cut from a very different cloth. Mute for the first 30 minutes of Paris, Texas, he’s a wreck of a man, the western pioneer lost in the American desert without so much as a horse. He’s both a cipher and a symbol for Wenders and Sam Shepard, but Stanton has no interest in any of that. Instead of grand empty gestures he embodies Travis transparently, the numbness and abnegation, a blankness that speaks volumes. And then when he slowly unfurls and connects with his young boy, when he unburdens himself to his wife, these are some of the most honest, heart-wrenching and dare-I-say hopeful expressions of masculinity the movies have to share with us.

Harry Dean, Harry Dean, you mean so much to us.