1. Far from Tallin: Narva on Estonia’s margins

In the city of Narva, in Estonia’s extreme east, right on the border with Russia, there is a statue of Lenin. It is a throwback to the period after the Second World War when the town, like the rest of the Baltic state, was occupied by Russia.

The 23rd Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival ran 15 November-1 December 2019.

The festival’s KinoFF spin-off ran 15-24 November 2019 in Narva and Kohtla-Järve in eastern Estonia’s Russian-speaking Ida-Virumaa region.

In 1944, most of Narva’s Old Town was destroyed by Russian bombing – with logistical and technical support from the UK. Postwar, its massive network of 19th-century textiles factories and nearby shale mines would prove valuable assets to the USSR, and tens of thousands of Russian workers were brought in to run these industries and rebuild the town Soviet-style (in what was also part of a broader strategy of Estonian ‘Russification’). The statue took pride of place in Peter’s Square, named for Tsar Peter 1 of Russia, who in 1700 was soundly beaten in open battle by King Charles XII’s outnumbered but more professional Swedish forces, but would change tactics and defeat the Swedes four years later, eventually making Narva part of the Russian Empire.

In a typical iconographic gesture of Soviet progressivism, Lenin is posed stretching an arm forwards, and a local legend has arisen that anyone at whom Lenin’s metal finger was pointing would have bad luck. This might seem a strange tradition, given the defining immobility of statues – but since Estonia regained independence in 1991, the statue has been taken off its pedestal, so to speak, and down from Peter’s Square, and now nobody quite seems to know what to do with Lenin. The statue currently resides in the Castle forecourt, ignominiously wedged between a wall and a row of metal industrial containers to which it now points – and, beyond those containers, towards Russia across the Narva river.

Yet despite this shabby treatment, you can still see flowers laid before Lenin’s feet, in a sign of persistent respect for the Russian revolutionary and the communist system whose values he embodied. Indeed the statue has become the paradoxical symptom of a territory which has changed hands and allegiances many times over the centuries, much as, every year in Narva, there are two reenactments of the 1700 Battle of Narva – one in November where the Swedish side wins, the other in August where victory goes to the Russians – “so everyone is happy,” as our Narva guide Elena Shuvalova put it. Lenin may point to the losers, but here, evidently, everybody can be a winner.

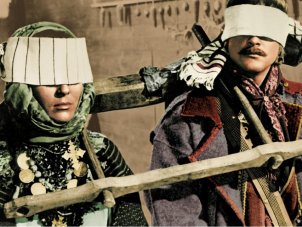

A statue of Lenin in Narva, Estonia

This, it turns out, is a delicate compromise in a region that is still to a degree contested. When, in 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and intervened militarily in eastern Ukraine, there was a suspicion in the West that ‘Narva is next’ in Russia’s constant testing and goading of NATO resolve.

After all, even though Narva is part of Estonia, the region seemed ripe for Russian infiltration. With over 90 per cent of its residents ethnically Russian, and many of those unable to speak Estonian at all (12 out of the 13 schools in Narva teach in Russian), let alone speak it well enough to qualify for voting rights or equal citizenship (one fifth of Estonia’s residents are disenfranchised), Russia had right at its edge a population whose disgruntlements and sense of exclusion might easily be manipulated – not least by the Russian media that are the locals’ primary source of information – into becoming the next Donbass. While Narva itself had little concrete to offer Russia, there would be obvious symbolic value in fomenting unrest within the borders of NATO and the EU.

☞ News from the front: Odessa 2014

The reality, though, is more complicated. The people of Narva, and of much of the Ida-Viru county that contains it, may identify racially, culturally and linguistically with Russia, but when they look where Lenin is now pointing, across the river to Ivangorod on the Russian side, they can see for themselves the inferior infrastructure, lower salaries and worse pensions, and are not eager to abandon their current better deal for a worse one. Separated by a natural border, Narva and Ivangarod have historically sometimes been conjoined cities, sometimes rivals or even enemies, in a shifting relationship that can be gauged by the presence or absence of a bridge between them. Currently, besides the visible remains of an older, destroyed bridge, there is the so-called ‘Friendship Bridge’ – but as Shuvalova pointed out, the name is “kind of ironic, because there are customs points at both sides.” Narva is as much divided from, as connected to, its Russian neighbour.

Estonian attitudes towards their country’s eastern region are also shifting. Where a previous generation, still smarting from decades of oppressive Soviet control, was resentful, even hostile, to their native Russian population, Estonia’s millennials have proven far more curious about Ida-Viru; and the state, nervous about the possibility of Russian subversion, has of late been investing in the region, setting up its own Russian-language media to rival Russia’s propaganda, and creating cultural capital there. The Kreenholm cotton factories in Narva may have closed for good in 2010, leaving over 8,000 people unemployed (at its peak it employed many more thousands than that), but parts of it are now used for artists’ residencies, while the courtyards of its now derelict buildings have accommodated music concerts.

This in turn has created a boom-time for tourism, with new events like the two-year-old music festival Station Narva (organised by Tallinn Music Week) attracting more attendees than can be accommodated in local hotels. Narva is now Estonia’s fourth most-visited city, and is making an active bid to become the Culture Capital of the European Union in 2024. The expression ‘Narva is next’ has now been proudly re-appropriated by the local tourist industry, and if Narva remains on the very edge of Estonia, the Euros spent there by visitors are bringing in margins of a different kind.

2. KinoFF kickoff

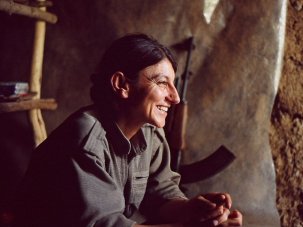

Black Nights Film Festival’s Kinoff sidebar launches at the Kohtla-Järve Culture Centre

As part of an effort to make Estonia’s north-east feel more integrated, this year’s Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival initiated an offshoot in Ida-Virumaa called KinoFF. Divided between Narva and Kohtla-Järve to the south, this is an outreach programme designed to introduce the glitz and glamour of the film festival experience to the eastern region, as well as a selection of 20 or so films that would not normally get distribution there. The Kohtla-Järve chapter of this Black Nights side festival launched in the city’s Culture Centre, a monolithic Stalinist building erected in 1953, and still decorated with a prominent hammer and sickle over its grand entrance.

There were drinks, canapes and live music in the opulent lobby, and a series of introductory speeches in the auditorium – prompting one heckler at the back to implore those onstage just to get on with the movie. The opening film – Anna Parmas’ Another Woman – was a low-brow, middle-aged domestic romantic comedy evidently chosen for its populist appeal, as a lure for viewers who might otherwise be reluctant to cross the festival threshold.

Another Woman (2019)

KinoFF is very much tailored towards its immediate setting, exhibiting only Russian-language titles to ensure that the fledgling festival would be well attended by Russophone locals. This may of course change in subsequent years once the festival has established itself and found its audience. Still, for now it marks KinoFF as very different from a more ‘international’ festival. While most of the films showing at KinoFF, apart from Another Woman, were also screening in the Black Nights programme (and were indeed programmed in Tallinn), not all the Russian titles that played the Tallinn festival also made it east – like Russian-born, Estonia-based Ksenia Okhapkina’s Immortal, an experimental documentary on Russian identity and control which has already won itself a slew of festival awards.

Immortal trailer

Also absent was Ksenia Ratsushnaya’s Outlaw (Autia), which had its world première in Tallinn, but which also featured LGBTQ themes – and explicit gay scenes – that would in all probability see it indeed outlawed in mother Russia, and no doubt made it a risky programming option for KinoFF’s inaugural festival. Outlaw is an odd film, celebrating queer culture and lamenting queer exclusion and oppression, while also, by presenting the LGBTQ community as bestial, ultraviolently hedonistic and gratuitously murderous, somehow only reinforcing the very kinds of demonisation that it apparently seeks to dispel. It also, rather surprisingly for a gay film, has a disproportionate focus on near-pornographic cis-het sex.

Outlaw trailer

One film screening at both Black Nights and KinoFF also managed to forge a link between Estonia and Russia. Valeriya Gay Germanika’s The Wolf Wood (Myslennyy volk) follows an estranged mother and daughter (the latter herself a young mother) who, after spending a frightening night together in the woods and then another in a rural home (with something monstrous at the door), are briefly reconciled with one another and to a better future together, until the spell breaks, leaving reality and loveless stasis to return. A postmodern fairytale and allegory of a Russia in transformation and at wild odds with itself, The Wolf Wood features wolves (real and CGI) and wolf masks aplenty. The wolf also happens to be the official mascot of the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival – an icon which, altered for KinoFF, appeared onscreen dressed as a babushka.

KinoFF 2019

3. Happy families

The best film that I saw during my stay at Black Nights, A Family, did not screen as part of KinoFF, and was not even Russian, but it nonetheless spoke to two of the themes that dominated the very essence of KinoFF: a turning towards Eastern Europe, and that sense of simultaneous belonging and not belonging that informs any culture caught in a marginal interzone.

☞ Salomé Lamas on her threshold foray Extinction: “I can’t tell apart my life from filmmaking”

Like Ariel Kleiman’s Partisan (2015) and Steven Kastrissios’ Bloodlands (2017), this feature debut from director Jayden Stevens, which he co-wrote with his DP Tom Swinburn, is an Australian film shot and set in the east of Europe. Featuring a cast of Ukrainian actors who all deliver their deadpan dialogue in the local tongue, A Family is a film of bleak drabness whose mundanities are lightened by a strong streak of absurdity, and whose artificial set-up (an Australian-made Ukrainian film) is reflected in its very narrative.

For the Christmas family get-together that joyless Emerson (Pavlo Lehenkyi) orchestrates in his barely furnished home is in fact an elaborate fiction, with his visiting mother, father, brother, sister and bad-egg uncle all in fact local strangers – and as non-professional as Stevens’ cast – whom Emerson has hired to help him shoot a home video. As they work through the screenplay of banal family conversations that Emerson has written and printed for them on his old computer, young Olga (Liudmyla Zamidra), who is playing Emerson’s younger sister Ericka, keeps veering off script and introducing parts of her own personality into this scenario – leading Emerson eventually to find a new family arrangement with Olga and her mother Christina (Tetiana Kosianchuk).

A Family trailer

As all these characters are lost in their difficult domestic dispensations, and the ‘loving family’ is presented as something more akin to fantasy role-play than to reality, Stevens brings to his materials a dry drollery reminiscent of Aki Kaurismäki or even Charlie Kaufman, while satirising the provisional, often arbitrary nature of our relations with others. If lonely Emerson keeps trying ridiculously to put himself at the centre of his movie before finally yielding control to others, then the last word in Stevens’ film (and its moral) is given to a character who is also an extra, making A Family a reflexive story of de-centred people struggling to find a way through complex interpersonal labyrinths of their own making.

As a parable of alienation and displacement, its funny (-strange and -haha) presentation of the human condition maps neatly onto the contested country of Ukraine where its mannered dramas unfold, and also onto Estonia’s Eastern border, where everyone’s sense of identity and affiliation is confused, and Lenin’s ideological certitudes can no longer give clear direction.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.