Web exclusive

Guy Maddin’s latest whatsit The Forbidden Room: not nonfiction, but properly bonkers.

Somehow, even after a week of full immersion, I can’t say I saw enough at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival to take a completely accurate temperature of the programme, but I think I can safely confirm the festival’s reputation as a somewhat schizophrenic launcher of both excitingly ambitious and frustratingly conventional nonfiction films. I was there to help represent Charles Poekel’s Christmas, Again, a fiction feature I edited, and to attend events hosted by the Sundance Institute’s Documentary Film Program. My second consecutive trip to Park City was at turns exasperating and inspiring.

22 January-1 February 2015 | Park City, Utah, USA

For the past few years, as expanding ideas of what nonfiction movies can be have been embraced by festivals and audiences worldwide, Sundance has been largely seen as behind the curve, clinging to more traditional, television-style modes of filmmaking. While this take has never been completely fair (great work like The Oath (2010), Position Among the Stars (2010), Cutie and the Boxer (2013), The Overnighters (2014), 20,000 Days on Earth (2014) and more have premiered in Park City over the last five years), the idea that Sundance is behind the times in terms of its relationship to cinematic documentary persists because it remains true that no festival premieres more glitzy and topic-driven movies than the sales-obsessed Sundance.

These subject-driven films are made in what might even be called the Sundance Style. There is often a kind of epidemic of over-certainty in many of these documentaries, an aesthetic devaluation of essential cinematic qualities such as ambiguity, mystery, ethical uncertainty, tension and subjectivity in favour of info-driven, black-and-white journalistic reportage, which can result in a denial of the inherent, messy power of nonfiction. Think Waiting for “Superman” (2010) or even Life Itself (2014) or… you know many, many others. These films can obviously be very good and they obviously have a place and Sundance is obviously the best festival for them to be.

Subject-driven and traditional does not necessarily equal ‘bad’. This year’s slate includes Big Topic films like Brett Morgen’s Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck and Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief, neither of which I’ve seen but both of which have gotten some raves among the art-minded set.

Listen to Me Marlon

I really enjoyed Stevan Riley’s ambitious celebrity portrait Listen to Me Marlon, which stuck to its unique, hypnotic style and won me over in the end. I also greatly enjoyed Bryan Carberry and Clay Tweel’s Finders Keepers, which has a crowd-pleasingly twisty story and is as Sundance-y as it gets. (I also have to mention that my longtime producer Douglas Tirola absolutely knocked it out of the park with his formally traditional but very good DRUNK STONED BRILLIANT DEAD: The Story of the National Lampoon.)

These films, however, do not a great festival of cinema make. Two documentaries I saw left me in such a state of irritation that I only half-jokingly complained to a companion that maybe I just didn’t like movies anymore.

The first, Jill Bauer and Ronna Gradus’s Rashida Jones-produced feature Hot Girls Wanted, which aims to be the definitive portrait of the multi-billion-dollar amateur porn industry, is such a mess of poor choices and half-realised characterisation that its problems transcend the typical complaints about Sundance’s over-reliance on issue-driven fare. The lead characters (several young women making the sometimes-pained choice to participate in the business of having sex on camera for money, and their slacker dude agent who facilitates it all) are all compelling and have plenty to say about the contradictions inherent in their work, but the filmmakers simply aren’t nimble enough to handle the complexities of representation brought up by the subject.

Hot Girls Wanted (2015)

In one scene, for example, a young woman struggles to explain to her mother her choice to be a porn star and the camera lingers for a painfully long time while the two women sit still, having nothing more to say to each other. While I’m all for revelling in the uncomfortable relationship that often exists between subjects and camera, it seems clear that the filmmakers are simply waiting for an extra dramatic moment to occur, which is likely being limited – not facilitated – by the presence of the camera.

When so much of the rest of the film is swooping info-graphics and conventional music, moments like this make it clear that the film’s narrative machinations are simply a more insidious form of objectification of these women. Though there were whispers that the film may be heading back to the edit room (even though it sold for what was surely a nice sum to Netflix), it will take a lot of work to prevent Hot Girls Wanted from essentially replicating the culture it aims to critique.

I was equally offended by Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi’s Meru, a conventional mountain-climbing documentary which has plenty of dramatic twists and nice images, but displays so little self-awareness that it becomes an unintended scathing critique of masculinity. A few days later I saw Doug Aitken’s Station to Station, which played in the festival’s art-minded New Frontiers section. Sadly there’s little art amongst all the art-talk; this semi-documentary is a cringe-worthy parade of celebrity philosophising and sub-MTV editing that felt like watching an off-cable variety show (on a bullet train).

The Forbidden Room (2015)

Maybe it’s just not the role of Sundance to launch smaller art films, you may say. Knowing (or having just met) a few of the programmers, I think I can safely report that they would disagree. Simply put: Sundance is America’s most important festival and therefore has a responsibility to the medium of cinema. I think its organisers would approve of this mission, even while their programming consistently leans predictable. It has long been the case, though, that if you look in the right places, Sundance has plenty of great work to showcase and this year was no different.

Guy Maddin’s The Forbidden Room may not be nonfiction (except, perhaps, as an observational portrait of the artist’s exuberant, demented, movie-movie mind), but its presence in the festival serves an immediate rebuttal to the idea that Sundance is all glamour and convention. The film may feature movie stars like Charlotte Rampling, but it’s so unwieldy and inspired (and exhausting, but in the best possible way) it felt like a nuclear bomb vaporising all the infotainment in its blast zone. The Forbidden Room has more ideas in ten minutes than most filmmakers have in their entire oeuvres; Maddin jumps into the murky waters of lost styles of nutso movie storytelling and delivers back everything he finds, and the result is properly bonkers.

Instant impact? Frida and Lasse Barkfors’ Pervert Park

I missed the big documentary award winners Cartel Land and The Wolfpack, but both had enough of a mixed reaction among the chatterers (a great sign) that I’m excited to catch up with them on the festival circuit.

It bears mentioning here that the US and World documentary juries alarmingly gave away “impact” awards while eschewing some honours for craft – the US jury gave no editing award and the world jury gave no cinematography award. The winner of the World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award for Impact, Frida and Lasse Barkfors’ portrait of a community of ex-sex offenders in Florida Pervert Park, features (like Kim Longinotto’s Dreamcatcher) an essential, meaningful story, classically if sometimes dully told. Maybe it was a bit too formally traditional for me, but I can’t deny the powerful effect of its steady patience with the typically too-easily dismissed. Still, I’m not sure how the film can make an “impact” just after its US premiere. Doesn’t that take a minute?

The Chinese Mayor (2015)

Better was The Chinese Mayor, Hao Zhou’s look at Datong mayor Geng Yanbo and his efforts to remake his polluted city before fate (i.e. the Party) intervenes. The film is remarkable not only for its unprecedented access to such a high-ranking Chinese official but for its astonishing restraint and subtlety. Lurking just beneath Hao’s coolly observational style is a meta-freakout at the sheer insanity of the access and its potential consequences. Yanbo’s (and the film’s) mask slips in the last 15 minutes to quietly devastating effect. I thought about no film more intensely, which can be partly attributed to Hao’s open-ended, unobtrusively provoking style.

Meanwhile, two of the best films I saw were complex, ambiguity-rich experiences, which strikingly demonstrated the benefits of filmmakers choosing cinema over simple transfers of information. Lyric Cabral and David Sutcliffe’s (T)ERROR relishes ethical complication in its portrait of ex-convict-turned-FBI informant Saeed ‘Shariff’ Torres, then transforms into a stunning, infuriating indictment of the current incarnation of the War on Terror with a twist in perspective that is as surprising as anything I’ve recently seen. The film is simultaneously great journalism and great filmmaking, but it doesn’t use the institutional norms of the former to overtake the requirements of the latter.

In the Q&A we learned that Torres allowed the first-time filmmakers to shoot him (often contentiously, as the movie smartly and provocatively shows) because he considers himself a ‘whistleblower’. Yet the filmmakers never use this fact as a shield (the word ‘whistleblower’ never appears onscreen), instead relying on a powerful sense of ambiguity on the narrative and meta-narrative level that prevents the film’s ‘message’ from becomingly damaged by oversimplification.

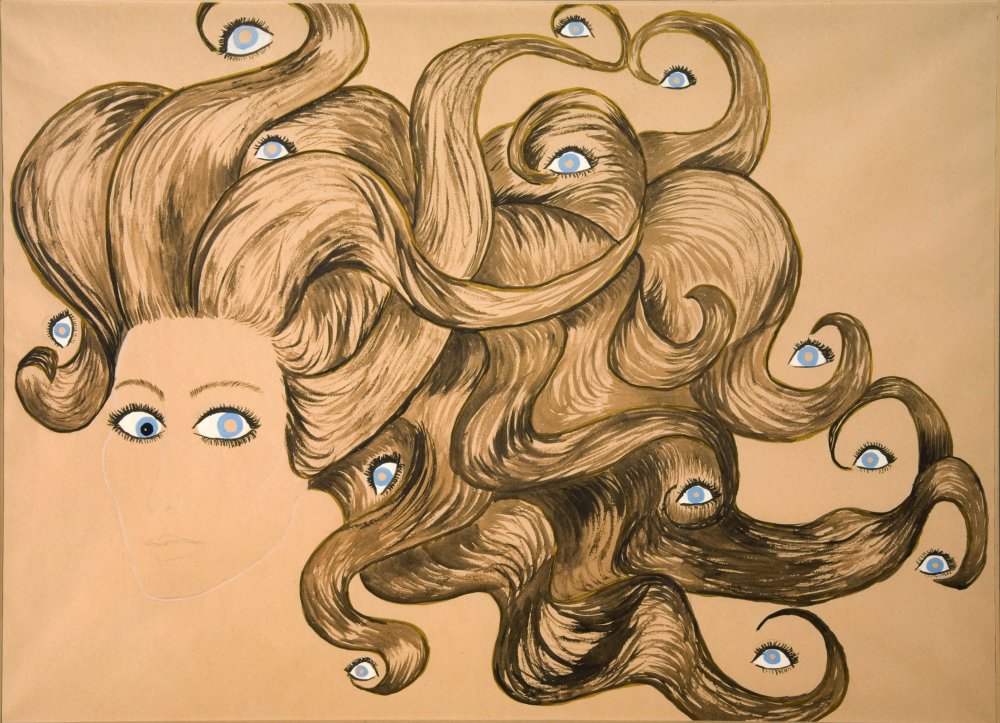

Abandoned Goods (2015)

The short Abandoned Goods, also directed by filmmakers (Edward Lawrenson and Pia Borg) who crossover as journalists, uses haunting music, abstraction and an unconventional structure to tell the story of the Adamson Collection, a recently discovered trove of art from asylum patients that brings into question the complicated relationship between creativity and madness, art and therapy. What could be a television-style art-doc becomes a deep, cinematic journey because the filmmakers know how to use forms to communicate something more profound than just the fact that the art exists. The incredible discovery of these pieces could sustain even the most boring, fact-driven film, but Abandoned Goods dares to do something more exciting.

So my self-selected Sundance (I chose to avoid things I might hate after the double whammy of Hot Girls Wanted and Meru) wound up quite invigorating and ended on a bit of symbolism. The last movie I saw was Bill and Turner Ross’s Western, a film I’d seen many cuts of during the editing process, but which stunned me on the big screen in its final version. Using images and representations from the classical western genre as their visual entry, the Rosses observe a real-life, unfolding drama on the US-Mexico border.

Western (2015)

Like their previous films (45365, 2009, and Tchoupitoulas, 2012), Western is an intense, detail-rich study of a place, but this time there’s a floating, unique tension between narrative and atmosphere that creates a distinctive experience. The symbolism was in the fact that the Rosses were even programmed here; as two of America’s best nonfiction filmmakers, their former exclusion from the ’Dance was always touted as evidence that the programmers of Park City didn’t ‘get it’. In the jam-packed screening I attended, that assessment felt something like a distant memory.

Sundance, for my money, seems to be wobbling towards a better understanding and appreciation of cinematic nonfiction, as the Ross brothers winning a special jury prize “for verité filmmaking” can attest. Still, it was a tiny, under-discussed movie just up the hill at the considerably less-fancy Slamdance that most excited me and had me believing in the future.

Tired Moonlight (2015)

Britni West’s Best Narrative Feature-winning Tired Moonlight, her debut feature, is a strange and glorious mix of idiosyncratic fiction, observational landscape documentary and bad poetry that simply blew me away. Burnt-beautiful and flowing like a kinky Montana creek, it’s an affecting reminder that cinema can and should be the territory of the artist creating new forms by capturing and editing the particular world she inhabits. This is eye-opening filmmaking that must be seen by lovers of movies everywhere but would never, ever get invited to Sundance. I hope that dynamic is changing and we need to keep stomping our feet and waving our arms madly until it does.

In the March 2015 issue of Sight & Sound

Park City lights

Despite its reputation as a magnet for predictable indie fare, the festival saw a handful of films that might just rank among the best of the year. Vadim Rizov reports.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.