Now go wash

Unclean! Unclean! Unclean! Can we make this the new mantra, @prewarcinema and @tapestore?

“Unclean Cinema”? You know what I love? Documentaries that are “non-productive, uncomfortable, even unclean.” I love them a whole lot.

—Eric Hynes (@eshynes), 5 March 2014

There is a slash between the ‘T’ and the ‘F’ in the logo for the True/False Film Fest that might as well represent a train of thought running through the documentary world these days, and I’m not just talking about how more filmmakers are blurring the lines between fiction and nonfiction. In the days after the 11th edition of the festival, with filmmaker Jill Godmilow’s much-discussed diatribe against The Act of Killing bouncing around the internet, it became clear to me that the ‘slash mentality’ represented so succinctly by the True/False logo was less about hybridisation than it was a full embrace of what could be called unclean cinema.

True/False Film Festival

27 February-2 March 2014 | Columbia, Missouri, USA

I was at the festival premiering my new film Actress and two other films I had a hand in finishing, Amanda Rose Wilder’s Approaching the Elephant and Jessica Oreck’s The Vanquishing of the Witch Baba Yaga. It was my fifth straight time in Columbia, Missouri and I exhausted many words on the common interpretation of the T/F slash, talking about performances, realities and the fabricated structures at the heart of documentary.

These ideas, of course, go all the way back to one of the founding moments of nonfiction cinema when ‘Nanook’ grabbed that spear from the back of his closet. And even a cursory glance at the history of movies reveals these boundaries have been explored again and again. But the transformation of deep contradictions that have historically been considered unacceptable by mainstream culture into a branded, youthful spectacle has made True/False (and festivals like CPH:DOX, etc.) a place to gather and rally. The innovations may not be new, but the widespread, energetic embrace of the slash mentality is a defining trait of documentary today.

But changing notions about the meaning of the slash were all over the screen at True/False. The narrative tensions in Jesse Moss’ Sundance-premiering The Overnighters, for example, create the sense of watching a lion tamer at work.

The Overnighters (2014)

In this complex portrait of a preacher who runs a shelter for migrant oilfield workers in a North Dakota boom town, one gets the uneasy feeling that the unfolding revelations are so disconcerting that they might break the movie apart as we watch. It’s thrilling to see the structures Moss creates to hold the thing together, to expose some truths and obscure others. The slash mentality exhibited here, especially in the thrilling last act, is a bold embrace of the chaos/structure dichotomy of nonfiction.

Meanwhile the animated, live-performed Dusty Stacks of Mom, the austere, ethno-sensory Manakamana, the chilling, racially provocative Killing Time, the gorgeous, mysterious Mille soleils and others found exciting ways to embrace their own slashes.

One of the things so invigorating about this year’s lineup was that the word ‘hybrid’ was never overly fetishised. Formal ambition isn’t just about integrating fictional elements into nonfiction work. The slash mentality in Life After Death, Joe Callander’s humorous, complicated look at the relationship between a twentysomething Rwandan and the Christian couple that cares for him, for example, was in the film’s exploration of the tricky lines between satire and humanism, critique and support. Even the selection of Richard Linklater’s masterful Boyhood as the closing night film was more about its documentary-like means of production and rare observation of real maturation than about a blurring of fictional/nonfictional elements.

Life After Death (2014)

It wasn’t until the festival was over, though, that I had the chance to fully comprehend the shifting meaning of that slash to me. I get awfully heated sometimes defending the rights of we filmmakers to make nonfiction by any and all means necessary, but as I stood in front of a room full of journalism students, in a pre-planned talk just after the festival (on the campus of Columbia’s University of Missouri, which is home to the oldest journalism school in the country, a geographical situation that makes T/F even more interesting), it became clear to me that the slash was more than a cavalier marketing gimmick or an essentially meaningless call to ‘break the rules’.

In journalism school, ethics is akin to religion – with good reason – and this idea of a dialectical approach to truth/fiction can be particularly upsetting to hear in certain corridors. My trip to Columbia actually began on a panel for the “Based on a True Story” conference – the very instructive annual meeting between the J-school and True/False, which smartly concerns itself with the relationships between documentary and journalism – and I think I said something semi-coherent about documentarians needing to have a basic understanding of the ethical rules that shape the backbone of journalistic practice before attempting to break them.

Later, as I stood in front of that classroom of wide eyes, perhaps feeling the need to cater my heretic message for the room, it became clear to me that I – and most filmmakers I respect and admire – are basically obsessed with ethics. It’s an issue embedded in our work. The line (slash?) between adventurous formal innovation and a solid ethical approach (along with an understanding that viewers are evolving and should be pushed further to understand the fabricated aspects of nonfiction) is maybe the most important thing to consider in documentary filmmaking today. That room (and dare I say the journalism institution itself) brought out my need to defend Victor Kossakovsky’s great maxim, “Documentary is the only art, where every aesthetical element almost always has ethical aspects and every ethical aspect can be used aesthetically.”

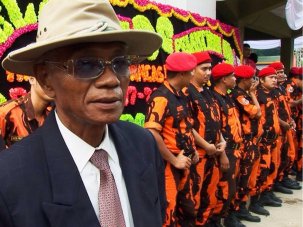

Killing Time (2014)

The embrace of the tensions between ethics/aesthetics, and the excitement around the conversations these dialectics create, are some of the reasons many view today as a sort of golden age for nonfiction. It was upsetting, then, as I passed through security at the St. Louis airport, to see my phone vibrating with flabbergasted reactions to Jill Godmilow’s angry Indiewire op-ed called Killing the Documentary: An Oscar-Nominated Filmmaker Takes Issue With ‘The Act of Killing’. Joshua Oppenheimer’s film was a selection at True/False 2013 and was obviously one of the big slash films of last year. So this felt like an attack on an idea.

The piece raises plenty of valuable questions (including how little we know about the actual rank and relative importance of the onscreen murderers), asks many questions rather obnoxiously (uses of words ‘obscene’ and ‘pornography’ are particularly eyeroll-inducing) and shakes its fist in the general direction of the makers and fans of new, ambitious documentaries.

Godmilow’s basic complaint is that the film is too concerned with sensationalism to stop and do the work it should to educate its audience, which includes other documentary filmmakers, who should be debating the awful realities in Indonesia and the questions about representation that Oppenheimer (and his team of Anonymous Indonesians, a crucial aspect Godmilow seems to forget) raises.

The Act of Killing (2012)

I believe the film, as a work of art, brilliantly put this all on the audience and I strongly disagree it isn’t aware of its complexities. But the most annoying part of the piece is that, as filmmaker A.J. Schnack points out in his great response, we in the documentary community have been having these debates for some time now – with late-night arguments, written pieces and through social media – and perhaps most importantly, with the films we make.

I would go as far to say that slash between those two words at that one festival has come to succinctly symbolise the ongoing conversation about where to take nonfiction film. Critic Eric Hynes was the first person I saw to point out Godmilow’s description of the film as “non-productive, uncomfortable, even unclean.” There it is. Unclean cinema. It became clear to me after reading those lines that the meaning of the slash – and its functional use in the documentary world – was shifting for me. The slash mentality is essentially about embracing the dirty impurities at the heart of documentary filmmaking.

On one side we have the old bedrock belief that the primary function of documentary is to educate through cinema. Thus clarity of purpose, measured movements and context are of utmost importance. Films can be ambitious (Godmilow’s own work is often considered as such), but the foundation must remain good journalism.

On the other side we have an embrace of what Godmilow seems to be calling the ‘unclean’: ambiguity, theatricality, use of surrealism (or other aesthetic devices), etc. The Act of Killing presents a chillingly complex set of scenarios and leaves them unresolved for the viewer. For me, this results in a profoundly disturbing cinematic exercise that respects my life experiences and political ideas as a viewer, while forcing me to question the very nature of human relationships. For Godmilow et al, the result is dangerous, dirty filmmaking that demands a moral correction and some lists of rules to follow.

The Act of Killing (2012)

One of the best things about documentary, though, is that the work can’t help but enter into a conversation about ethics, constructions, realties, layers, slashes and all that. It’s the nature of the medium; the films themselves are acts of expressive conversation.

Viewers are (or damn well should be by now) aware when watching a documentary that these tensions exist with every captured image and edited sequence. When we encourage ‘unclean’ formal ambition, we are advancing the dialogue. There are plenty of unethical filmmakers and troubling films out there to be discussed vigorously, but I would argue the documentaries that embrace openness, ambiguity and reveal their construction are more ethical than the ones that peddle old journalistic modes of ‘objectivity’, where problematic forms are generally more obscured by a familiar framing.

I start as a viewer/filmmaker/writer from a couple of unclean ideas. First, all documentaries are inherently exploitative to some degree because images are representational and there is an unbalanced exchange created when one records and edits a real human being or real situation.

Second, formal advancement requires audacious, sometimes even problematic aesthetic choices. The last thing we should do is reign in films like The Act of Killing and much of what True/False programmes because frisky movement is a vital aspect of evolution. To say there is even the possibility for ‘cleanliness’ in cinema is to deny its essential nature.

Viva the slash, long live the unclean. Long live a cinema that excites, angers and provokes, that makes things less comfortable, not more. Nonfiction films can be crucial for bringing conversations out from the shadows, into the active currents of society. Let’s do our best to not push the most interesting, emerging parts of those conversations back underground.