Web exclusive

Note: this essay refers to the longer, ‘Director’s cut’ version of The Act of Killing, and to scenes edited out of the shorter theatrical cut.

Introduction

Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing documents the efforts of a group of small-time gangsters in Indonesia to re-enact, through cinematic genres, their roles as executioners in the 1965-66 government-sponsored killings of so-called Communists. These gangsters boast about their involvement in the murders and seize the opportunity to re-create their violent pasts in all their graphic and (in their words) “sadistic” detail.

For this reason, we could conceive of The Act of Killing as two films: Arsan and Amina, the gangsters’ film, and Oppenheimer’s documentary that interviews participants and captures events behind the scenes. The filmmakers of each – the gangsters on the one hand, Oppenheimer and his colleagues on the other – have different ambitions for their films and different stories that they want to tell. It is the tensions between these differing representations of history that drive The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer creating a dialectic between them that, as the title of the film suggests, culminates in the understanding of history as precisely an ‘act’.

These dialectical tensions between competing versions of history call to mind Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History. For Benjamin, the past of the “oppressed” must be wrenched from the historicist concept of history as a “continuum” of “homogeneous, empty time” that is defined by “the victors”. The past must be recognised instead as a “dialectical image” wherein the past is called forth into the present.

Both approaches to history can be found in The Act of Killing. The tensions permeate the very form of the film, but are also played out in the figure of Anwar Congo. Anwar, one of the death squad leaders, becomes the focus of the film as he appears increasingly unsure about the kind of (hi)story he wants to tell. His journey is one of what Benjamin would call “awakening” as he reaches a new understanding of the significance and implications of his violent deeds. Oppenheimer represents the process formally in order to provoke an “awakening” on the part of the viewer. In relation to this process, Benjamin’s ideas on surrealism, storytelling and epic theatre are also relevant. The gangsters’ notion of history is eventually shattered until all we are left with is fragments. It is in this fragment that Anwar and the audience discover killing as an ‘act’ or, more specifically, a gesture. In this discovery, the killers’ humanity is restored to the act but the implications of this are unsettling.

1.

“To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognise it “the way it really was” (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger. Historical materialism wishes to retain that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to man singled out by history at a moment of danger. The danger affects both the content of the tradition and its receivers. The same threat hangs over both: that of becoming a tool of the ruling classes.”

— Benjamin, Thesis VI, Theses on the Philosophy of History

Anwar and his companions set out to tell what they call the “true story” of what happened in their city, Medan, during the violence of 1965-66. Until now, their violent pasts have only been acknowledged (and feared) locally. They were acting on behalf of a government which maintains control – albeit in a more democratic guise – to this day. Although they were rewarded financially for their roles in the mass killings, these individuals remain small-time gangsters and local celebrities with no political influence, relying instead on intimidation, boasting and chauvinism for power and status.

At the time the film was made, the killings they perpetrated had not been officially recognised, let alone apologised for. Notably, the propaganda film which was compulsory viewing for generations of Indonesian children made no mention of the killings, instead focusing on portraying the Communists as the aggressors. In such circumstances we can begin to understand why Anwar is so desperate to be recognised for the actions which are the source of both his local notoriety and his nightmares.

His and his companions’ own past has been smothered by what Benjamin labels the “continuum of history”, the version of history written by the victors. Anwar has become, quite literally, a “tool of the ruling classes”, an ambitious petty criminal hired to do the army’s dirty work. Anwar’s past is just as “oppressed” and in need of salvage as that of his victims. The killings have been covered up by the government and no process of collective remembrance or mourning has yet been instigated. This is problematic because, as Catherine Malabou argues (in her essay History and the Process of Mourning in Hegel and Freud, in Radical Philosophy issue 106, March/April 2001), “there is no history… without mourning.”

Anwar’s exclusion from history could provide exactly the “moment of danger” which for Benjamin enables a “memory” to “flash up”. However, Anwar’s stated approach – to “show the true history” – cannot achieve this. For Benjamin, to try to re-experience the past and establish an alternative historical narrative to counter that of official history is simply to replace one form of universal history for another and to fall into the trap of historicism.

In Arcades Project, he describes Ranke’s dictum as “the strongest narcotic of the century”. Those who succumb to this kind of history occupy a state of consciousness in which they cannot recognise history as Benjamin intends it to be recognised. In a literal sense, Anwar has taken refuge in intoxication in order to avoid the “flashing up” of that memory. He admits to taking drugs, dancing and drinking in order to forget the horrors he inflicted on others. In this state he accepts his status as a “tool of the ruling classes” and complies with the version of history written by “the victors”.

In this environment, Anwar is described as a “happy man” who performs the cha-cha whilst around his neck hangs the wire he’s just used to demonstrate how he strangled hundreds of Communists. He and his companions live as “free men” in a haven of wealth and impunity where they revel in their powers of exploitation and indulge in the so-called “relax and Rolex” lifestyle. (Throughout the film, the men claim that the Indonesian word for gangster, premen, comes from the English “free men”.)

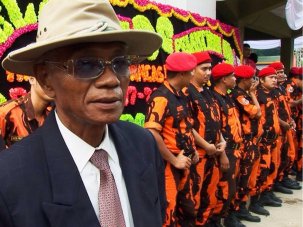

Oppenheimer reveals that this attitude exists at all levels, from Herman – Anwar’s henchman and rank-and-file member of the Pancasila Youth (a paramilitary organisation that played a key role in the 1965-66 killings) who launches a brief and unconvincing political campaign motivated by potential opportunities of bribery – to the Vice President of Indonesia, whose speech to the Pancasila Youth celebrates gangster culture and proclaims that “we need gangsters to get things done”. Later in the film Oppenheimer includes an excerpt from a chat show, broadcast by the Indonesian National Television Network, which congratulates Anwar and the rest of the Pancasila Youth for their commitment to the extermination of Communists and their use of more “efficient” methods of killing.

Not only are they keen to boast about their violent pasts; these individuals also invite us to admire their rewards. The example that stands out here is Haji Anif, introduced as “paramilitary leader and businessman”, who shows off his monkey and bird enclosures as well as his range of “very limited” crystal animals to the sound of Big Mouth Billy Bass singing Don’t Worry, Be Happy.

These ornaments are the trophies of murder and represent power over death. In this world, nature has been conquered and displayed. In all their shininess and newness, these precious objects hide the bloodshed that lies behind them and allow it to be forgotten or pushed aside, so these men can surrender themselves to the dream of the gangster highlife.

This process corresponds to Benjamin’s understanding of the realm of nineteenth-century Parisian arcades as a “fairyland”, a dream-world of displayed commodities that seduced the shopper into the consumption culture of commodity capitalism. The gangsters’ relationship to their material rewards is reminiscent of Marx’s notion of commodity fetishism: the labour that has gone into a product is masked and human relationships have been transferred from individuals to the things themselves. The very hands that delicately handle these ornaments have also killed hundreds of men. As in the “fairyland” of Benjamin’s arcades, the displayed fetish object becomes a means of sustaining the prevailing ideology and version of history maintained by “the victors”.

Formally, Oppenheimer allows the audience to enter the world of that dream. Scenes devised by Anwar and his companions for Arsan and Aminah are also used by Oppenheimer and edited in such a way as to become dream-like. This is particularly true of the re-enactment in which Pancasila Youth members enter a “Communist” village, attack its inhabitants and burn it to the ground. Oppenheimer uses slow motion and mutes the sound; the scene lasts for several minutes and the audience is invited to enter the reverie of the flames. However, an abrupt cry of “Cut! Cut! Cut!” shakes us from this dream and from the diegesis of Anwar’s film, back into ‘reality’. But we cannot remove ourselves from this dream so easily – we know that similar events did in fact take place and were perpetrated by or against the very individuals now acting them out. Oppenheimer creates a dialectic between the dream and waking worlds in order to bring about an “awakening”.

2.

“Just as Proust begins the story of his life with an awakening, so must every presentation of history begin with an awakening; in fact, it should treat of nothing else.”

— Benjamin, Convolute [N4,3], Arcades Project

“Is awakening perhaps the synthesis of dream consciousness (as thesis) and wakening consciousness (as antithesis)? Then the moment of awakening would be identical with the ‘now of recognisability’, in which things put on their true – surrealist – face.”

— Benjamin, Convolute [N3a,3], Arcades Project

The representation of the “dream consciousness” occupies an important part of The Act of Killing, since it is a necessary element in the route to what Benjamin calls “awakening”. In the words of Marx, quoted by Benjamin in Arcades Project, “the reform of consciousness consists solely in… the awakening of the world from its dream about itself”. In relation to history, Benjamin believed awakening could lead to recognition of a past that exists outside of the “continuum of history”.

Oppenheimer’s film traces and reflects the process of Anwar’s awakening and the struggles he experiences as he is jolted from his “dream consciousness” and the understanding of history that accompanies it. Oppenheimer presents this dream world only to shatter it, but by representing its destruction he reveals the process by which what Benjamin calls a “true picture of the past” might be revealed.

The film’s “true surrealist face” is not to be found in its dream-like, “unreal” aesthetic. In fact, in Arcades Project Benjamin criticises the Surrealist movement (and Louis Aragon in particular) for dwelling too much “within the world of the dream”. Rather, the awakening process in The Act of Killing is brought about through its fragmented structure. Benjamin structures his own One Way Street and Arcades Project as aphoristic fragments. In Prisms, Theodor Adorno argues that this fragmented structure enables meaning to emerge “through a shock-like montage of the material”. For Benjamin, a fragmented structure could create space for the “true picture of the past” to break through the expanse of homogeneous history.

The Act of Killing consists of scenes that exist in and of themselves that are often starkly juxtaposed with those that precede and follow them, creating the “shock” effect that Benjamin argued could bring about an awakening. Such juxtapositions occur between representations of the past and the present, or between what we may call the ‘dream’ images of Anwar’s re-enactments of his imagined past and the ‘documentary’ material shot by Oppenheimer. (Although, whilst Oppenheimer makes contrasts, he also blurs the distinction between fiction and documentary elements, as I’ll come to.)

The film is punctuated by shots of present-day Indonesia – streets, horizons, shopping malls – that are muted in both colour and sound. These calm, dull scenes are interrupted by loud, dazzling, vibrant re-enactments. Such interruptions create a dialectical relationship between two states of consciousness and evoke the existence of a “homogeneous, empty time” that is shaken by another version of history. Visually, Oppenheimer is performing the task of Benjamin’s historical materialist: he “blasts the epoch out of the reified continuity of history” and “explodes the homogeneity of the epoch, interspersing it with ruins – that is, with the present.”

The bodies that were mutilated on rooftops and dumped in rivers and that now haunt Anwar at night are lurking below the surface of history, waiting for the “now of recognisability”: the moment at which they will be acknowledged in the present. The abruptness with which the violent past disrupts the present reflects the violence of that history itself: contemporary Indonesian society was founded on fear and bloodshed. These interruptions act as a reminder of Ariel Heryanto’s statement that “underlying the power of any long-running domination in history is physical violence on a large scale and a sustained threat of its potential occurrence.” (See the essay Screening the 1965 Violence, in Joram ten Brink and Joshua Oppenheimer’s compendium Killer Images: Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence.)

For Benjamin, official history is inevitably a history of barbarism, since “all rulers are the heirs of those who conquered before them.” This is especially true of Indonesia, where there has been little political change since the murders were committed. But Oppenheimer bursts this apparent historical homogeneity, offering the past a significance in the present by rupturing, rather than smoothing out, the connection between them.

3.

“Historicism contents itself with establishing a causal connection between various moments in history. But no fact that is a cause is for that very reason historical. It became historical post-humously, as it were, through events that may be separated from it by thousands of years. A historian who takes this as his point of departure stops telling the sequence of events like the beads of a rosary.”

— Benjamin, ‘A’, Theses on the Philosophy of History

Oppenheimer is unconcerned with historical chronology or continuity. Throughout the film we witness Anwar, now (playing) ‘dead’, now alive, perform re-enactments with a constantly changing hair colour (which was promptly dyed from white to black after watching himself perform one of the first re-enactments). Oppenheimer shows Anwar oscillating between brutality and regret: at one point he expresses his feelings of remorse toward the mothers and children of his victims; shortly afterwards he is shown ripping a doll, which represents the child of a Communist, to shreds.

The Act of Killing is not a film about justifications or explanations; Oppenheimer is neither defending nor attacking Anwar’s deeds. He is generating a process of memory. In eschewing explanation, he is telling a kind of story which, as Benjamin argued in The Storyteller, lent itself much more to memory than that which seeks to contextualise.

Oppenheimer contrasts his approach to history with that of Anwar, who through his film wants to historicise his actions and justify them. For example, he is unsure of where in his film to insert the scene in which Herman, dressed as a Communist drag queen in the middle of the jungle, threatens to devour Anwar’s ‘liver’ whilst Anwar’s ‘decapitated’ head looks on in disgust. (By this point Anwar and Herman seem to have abandoned their aim of representing “the true history”). In the end he decides that the scene should come at the beginning, since these taunts could be used to excuse the violent deeds that come later. However, he cautions, it would need to be clear that this occurred in a “time tunnel” in order to account for how he can be decapitated in this scene, but alive in later ones.

This kind of cause-and-effect narrative not only characterises the storytelling of classical Hollywood cinema, but is akin to the kind of history that for Benjamin belonged to the “homogeneous, empty time” of historicism. Continuing to work within this framework, Anwar’s film cannot sufficiently break free of dominant historical discourse to recognise the past the way Benjamin envisioned. For Benjamin, in order to think historically, continuity and narrative must be ruptured. As he describes in Thesis IX, the angel of history recognises the past not as a “chain of events”, but as “one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet”. Through fragmentation and juxtaposition, Oppenheimer favours the “flash” over the “continuum” and presents the past as a “monad”, rather than as a “transition” that is lost in the expanse of historicism. He rejects established practices in historical documentary of assembling facts, testimonies, footage and/or real locations that aim to provide an understanding of the past “as it really was”.

However, Oppenheimer includes scenes from Arsan and Aminah, as well as discussions amongst the gangsters about how their history should be represented, in order to draw attention to the contrived nature of historical narrative and its tendency to cover over histories that Benjamin would call “oppressed”. At one point, Anwar and his companions are preparing for a scene in which they will interrogate Anwar’s real-life neighbour who will play the Communist. On the set, Anwar’s neighbour asks if he can tell them a story which they may or may not wish to include in the film. The men are prepared to listen to the story because it is “true” and “everything that is in this film must be true”.

Through nervous laughter, the neighbour explains how, as a boy, he had to bury his own stepfather who had been murdered by the death squads and dumped at the side of the road. At the end of the story it is unanimously agreed that this story cannot make it into the film because it would be “too complicated to shoot” – and besides, “everything’s already been planned”. In such scenes, The Act of Killing exposes the ambiguities inherent in any claim to represent Anwar’s vision of a “true” history.

4.

“Epic theatre is by definition a gestic theatre. For the more frequently we interrupt someone in the act of acting, the more gestures result.”

— Benjamin, What is Epic Theatre?

By including such behind the scenes discussions, Oppenheimer distances the viewer from Anwar’s representation of history by exposing the process of its construction. Re-enactments and demonstrations are interrupted, adjusted and explained. In one of the first demonstrations, Anwar takes Oppenheimer to the roof of a toy shop. He explains that he killed hundreds of people in that very spot, and immediately begins to demonstrate how he dragged the bodies around the terrace.

He moves on to describe the method they came up with – strangling with a wire – but soon asks Oppenheimer if he can just show him instead. A companion agrees to sit on the floor whilst Anwar, addressing Oppenheimer and the camera, acts out and explains how he tied and pulled the wire. As Anwar recognises when he watches the scene later, he is not embodying the character of the executioner, but merely demonstrating it. He criticises himself: “Look, I’m laughing. I did it wrong, didn’t I?”

This kind of performance is reminiscent of Brecht’s notes on The Street Scene demonstration that he uses as a model for his concept of epic theatre. Here, the witness of a traffic accident “acts the behaviour of driver or victim or both in such a way that the bystanders are able to form an opinion about the accident.” The demonstrator establishes a distance between himself and his ‘role’ so that the audience can reflect on the performance and are not absorbed into the ‘illusion’. The explanations he includes in his demonstrations, which address the audience directly, offer what Brecht calls the “alienation effect”.

Benjamin argues that “the interruption of happenings” in epic theatre could produce “astonishment” on the part of the audience. We can equate this with the ‘shock’ that he believed could bring about an awakening of consciousness. Oppenheimer does not allow the audience to historicise Anwar’s actions; they are no longer contextualised or part of a homogeneous history. The interruption of a demonstration is akin to the “cessation of happening” that can call forth a memory that has been covered over by historicism. Of the violence that he perpetrated we can no longer ask “how this can still happen?”, as Benjamin’s historicist would; it has been extricated from its context and dropped into the present, detached from motivation and justification.

What were in themselves horrific acts of violence are deconstructed before our eyes and their brutality is diluted. What seem more unsettling and incomprehensible are scenes of ordinary activities inserted with no obvious explanation or purpose: Anwar visiting the dentist; Herman brushing his teeth. In this way, Oppenheimer offers us Benjamin’s very definition of surrealism: “a dialectical optic that perceives the everyday as impenetrable, the impenetrable as everyday”. By deconstructing the violence, Oppenheimer transforms it into gesture. The demonstrations and re-enactments encourage the viewer to reflect on the isolated gesture of killing, on the tiny details that make up a history of violence. It is in this sense that we should understand the film’s title. Oppenheimer wants to show that, as he told Der Spiegel, “the act of killing is always some kind of act, because otherwise you couldn’t do it.”

The focus on the act is relevant when we consider Anwar’s perception of himself. In order to commit such violence, he locates his behaviour within the culture of cinema. He compares himself to Sidney Poitier and his heroes are Al Pacino and James Dean. Whilst he was working for the death squads he was also selling cinema tickets. He tells us that after “happy movies” – “Elvis movies”, for example – he and Herman would go directly to the “office” to kill people, drinking, dancing and laughing. Still in high spirits from the film, he says, “it was like we were killing happily.” Their first-hand experience of the killings was therefore just as mediated as the re-enactments of those killings.

The extent to which killing is an ‘act’ is highlighted in certain scenes which blur the boundary between documentary and fiction. For example, when Anwar’s neighbour is interrogated as a Communist, he becomes extremely distressed and Herman jeers, “Let’s kill him for real!” At this point it is no longer clear who, if anyone, is acting. We realise that there is no clear distinction between ‘fiction’ and ‘reality’ here: all of these individuals were involved in these events ‘for real’; killing was as much of an act in 1965 as it is on this film set.

Oppenheimer presents Anwar not as a killer, but as someone who is constructing the appearance of a killer. There are countless shots of Anwar looking at himself in the mirror, adjusting his hair and dentures, admiring his own outfits and having make-up applied on the set.

Although he really did commit these violent acts, Anwar never seems to become the killer. Even in the re-enactments he is more often playing the victim than the perpetrator, and when he plays himself he is hardly convincing. He lurks in the background, and the one scene where he plays the interrogator is interrupted because he gets his facts wrong. He asks the ‘Communist’, played by his companion Adi, why he was recruiting people to join an illegal party. Adi reminds him that the party wasn’t illegal at that time, and the whole cast start laughing. Although unintentionally, Anwar can be compared to the actor in epic theatre who, Brecht explains, avoids “getting the audience to identify itself with the characters which he plays. Aiming not to put his audience into a trance, he must not go into a trance himself.”

The one instance when Anwar does appear to go into a “trance” and “become” his character, it is in the role of the victim. In this film noir-style scene he plays a Communist who is tortured and strangled by a death squad leader, played by Herman. Anwar is visibly moved during the scene and takes some time to recover.

Later, when he watches it at home, he is proud of his performance and asks his grandsons to come and watch. At this point we begin to wonder whether, for Anwar, killing will only ever a performance. However, once the scene is over and his bemused grandsons have left, he is clearly unsettled. In tears, he wonders: “did the people I tortured feel the way I do here? …Is it all coming back to me?”

5.

“If he is to live, man must possess and from time to time employ the strength to break up and dissolve a part of the past: he does this by bringing it before the tribunal, scrupulously examining it and finally condemning it.”

— Nietzsche, On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life

It is by encountering his own mortality (through cinema) that Anwar is offered the “revolutionary chance” of Benjamin’s historical materialist: a return to the humanity that has been denied to him by universal history. Although, as Nietzsche points out, the ability to remember is one characteristic that defines us as humans, there is a point at which, if one is unable to break free of history, man also loses all humanity. As Anwar re-enacts his own death he is struck by exactly the “moment of danger” that, for Benjamin, can cause a memory to “flash up”. He experiences his past as a fragment which encounters its “now of recognisability” and, in this moment, rejects the homogeneous course of history which has smothered his past.

According to Benjamin, “the concept of the historical progress of mankind cannot be sundered from the concept of its progression through a homogeneous, empty time”. By rejecting that history and submitting to ‘death’, Anwar is also rejecting the notion of progress and what Benjamin describes as its “exploitation of nature”. As a killer he claimed power over nature, calling the murders he perpetrated “unnatural deaths”. Now, he has surrendered to it. His dismembered corpse is scattered across a jungle landscape and his innards are devoured by monkeys. The protagonist of a film that thrives on fragments thus ends up in pieces himself. His severed head denotes his rupture from the burden of homogeneous history; he is transported to the afterlife where his body is reconstituted and he can dance beneath a waterfall.

The ‘afterlife’ scene seems to be one with which Anwar intended to end Arsan and Aminah. To the sound of an ethereal rendering of Born Free, two battered ‘Communists’ remove the wire from their necks, thanking Anwar and giving him a medal “for sending [them] to heaven”. Given Anwar’s position side by side with his victims, along with the lush landscape and euphoric music, it is safe to assume that Anwar has made it into heaven. We are left with an image of what James E. Young calls “common memory”: a memory of trauma that “tends to restore or establish coherence, closure and possibly a redemptive stance”.

This is a satisfying end to Anwar’s experience of ‘awakening’; now that he has realised the error of his ways, he can move on. Anwar is now able to truly live because he has condemned his past and freed himself from it. He has exercised what Nietzsche would call his “plastic power”, ie “the capacity to develop out of oneself in one’s own way, to transform and incorporate into oneself what is past and foreign, to heal wounds, to replace what has been lost, to recreate broken moulds”.

6.

“The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognised and is never seen again.”

— Benjamin, Thesis V, Theses on the Philosophy of History

Although Anwar experiences an awakening, Oppenheimer chooses not to end The Act of Killing with the euphoric afterlife scene. In fact, it comes as the penultimate sequence.

In the final scene Anwar takes us to the roof of a handbag shop – yet another execution site. He begins what has now become a routine demonstration of how he strangled his victims and stuffed the bodies into sacks. However, his demonstration is interrupted by his own gagging. The fit of retching lasts for minutes (although, ironically, nothing actually comes out). He pulls himself together and continues his demonstration.

Whilst doing so, he explains his actions to Oppenheimer: “I had to kill them… my conscience told me I had to.” At this, he begins to retch again. The Act of Killing film ends with a perturbed and frail-looking Anwar descending the stairs of the handbag shop.

Oppenheimer leaves us with an image of an individual who has still not managed to fully break free of history’s continuum. His body continues to battle with the kind of history that forces explanations. The final shot of The Act of Killing addresses Saul Friedländer’s concept of ‘deep memory’: a memory that, in Young’s words, “continues to exist as unresolved trauma just beyond the reach of meaning”. By ending The Act of Killing in this way, Oppenheimer does not allow the “closure” offered by “common memory”; Anwar is not redeemed. He has only experienced his past as a “flash” because the “now of recognisability” is only an instant that “flits by”. His gagging is an outward sign that he has recognised “the true picture of the past” but is not willing to accept it.

By placing these two radically different endings in succession, Oppenheimer creates the most dramatic juxtaposition of the film. He contrasts the two concepts of history and memory that have formed a dialectical relationship throughout The Act of Killing. By representing murder as gesture he allows Anwar a fleeting moment of redemption. For Giorgio Agamben (see Infancy and History), “in the cinema, a society that has lost its gestures seeks to re-appropriate what it has lost whilst simultaneously recording that loss.” In other words, cinema offers the chance to rediscover the gesture as a fragment of the past that has become lost in history.

The Act of Killing offers an “awakening of consciousness” that extricates the act from homogeneous history and humanises its perpetrators. Scenes of everyday activities – of brushing teeth, for example – appear as strange because there is something humanising about watching a mass murderer perform his ablutions.

Along with this awakening comes a sense of redemption because Oppenheimer has shown killers as human beings and has made it difficult for us to separate ‘good’ from ‘evil’ or ‘us’ from ‘them’. However, this awakening can only appear as a flash of euphoria because of the disturbing nature of this realisation. If these killers are human, then evil can exist in all of us.