Web exclusive

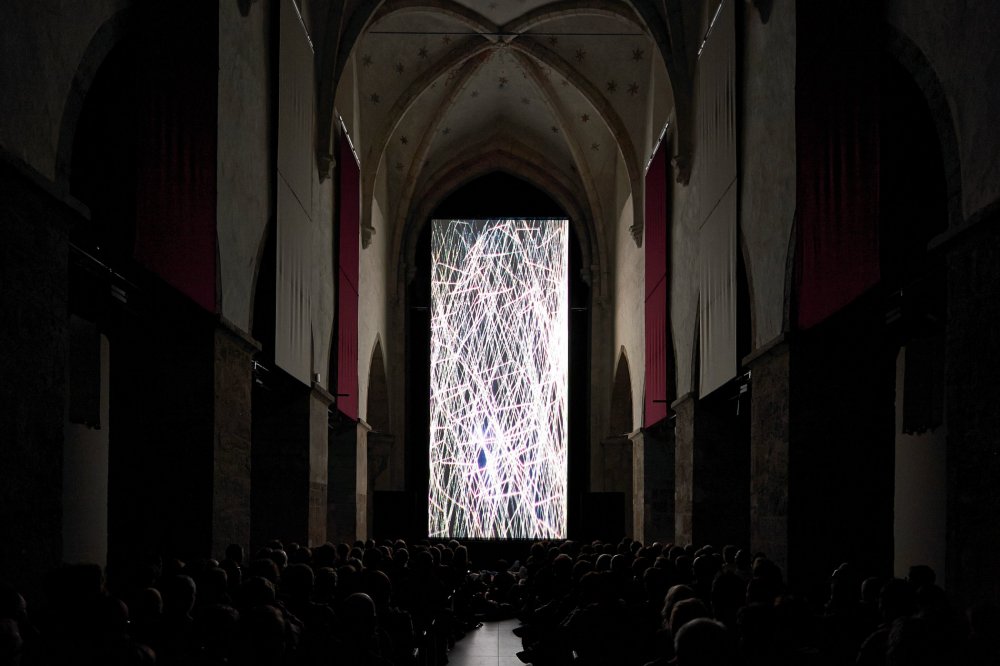

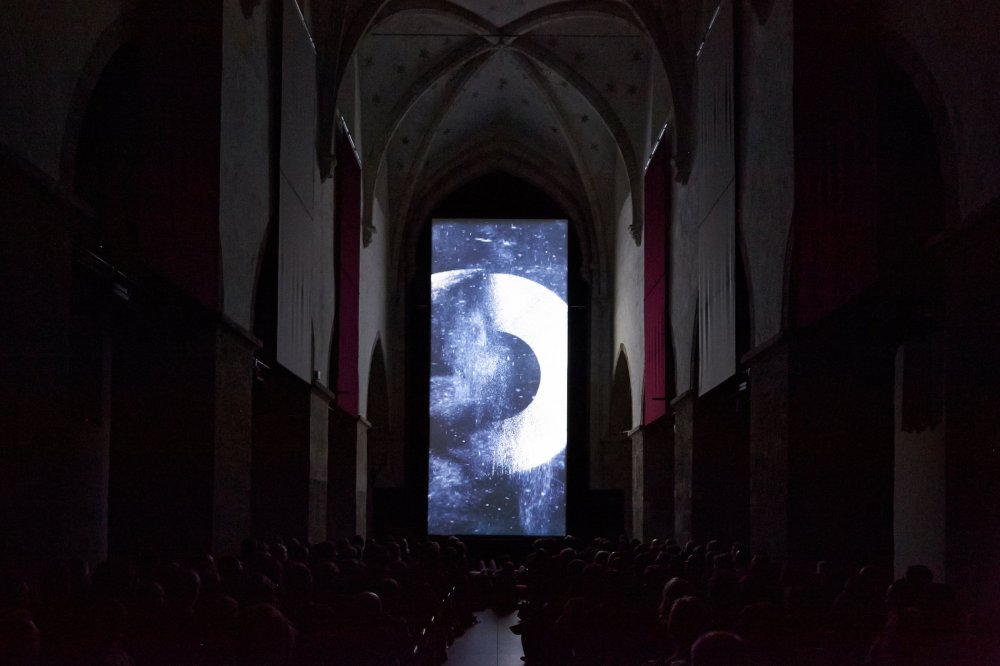

Esther Urius’s Vertical Cinema short Chrome, screened in the Arminius church, Rotterdam

Cinema seems irrevocably conquered, these days, by what Peter Greenaway once referred to as “the tyranny of the frame”. With its debt to the theatre (whose fixed seating and proscenium arch demand a one-way, single-space viewing experience), and to western painting traditions (whose canvas of choice is the parallelogram), the cinematic image is bound, for better and worse, to the rectangle.

International Film Festival Rotterdam (24 January 2014) and touring

It has nevertheless undergone changes. These have tended to be expansions outward: Polyvision, CinemaScope, VistaVision, Cinerama and so on. Upward equivalents are hard to find. Beautiful though panoramic views may be, along the horizontal plane at least, film has been standardised.

So if the shape’s here to stay, why not at least experiment with which way around you prop it up? That’s the basic question of Vertical Cinema, a programme of ten specially commissioned 35mm shorts, produced by Sonic Acts in collaboration with Kontraste Festival, the Austrian Film Museum, Filmtechniek BV, Paradiso Amsterdam, the European Space Agency, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) – which hosted the programme’s international premiere with two sold-out screenings on 24 January in the Arminius, a church dating back to the same decade the moving image was born.

The phrase ‘35mm’ has itself become a site of resistance – technological, and therefore also political – and in some way the medium was Vertical Cinema’s message: these shorts, projected onto a vertically hung CinemaScope screen, were aurally violent and unceasingly radical departures from narrative cinema. And yet, over the course of its 90 or so minutes – even over the course of one single short – the bedazzling intensity of the audiovisual onslaught had a durational effect. Which is to say, it acquired a narrative sensibility of its own.

Walzkorpersperre

It was deeply impressive. Some of these works grabbed me by the gut, slapped me around the ears and did funny things to my eyes before throwing me out of the Arminius and onto the cold wintry streets of Rotterdam in something resembling a mild state of shock.

Most indicative of the overall immersive effect was the sudden disappointment I felt when Johann Lurf’s Pyramid Flare – the penultimate in the programme – presented real-world imagery (of a modern pyramid building in Prague), which doubled as a rupture in the previously abstract canvas.

A silent rupture at that: not surprising for an event produced by the tellingly named Sonic Acts, nine of the films were as much about a punishing sound design as they were about upending horizontality, and so Lurf’s silent, five-minute film offered brief respite before Prins & van Boven’s Walzkörpersperre, an explosive light-and-sound engraving on the weathered concrete walls of a bunker, which saw many audience members finally make use of the earplugs handed out to them upon entry.

Spending time in the company of such aesthetically incessant stuff appears to prolong time itself: on the one hand the programme flew by, on the other even the shortest film, Rosa Menkman’s Lunar Storm, seemed to last far longer than its four-minute running time. No bad thing: glitchy, ugly and agitated, the film sucks you in and spits you out.

Colterrain

Durational abstraction enables imperceptible shifts. A colour change is narrative. So too is a vertical line’s gradual shift in axis. Take Tina Frank’s Colterrain, in which strikingly vertical lines move outward from the centre of the frame. Frank employed a Synchronator device for the work, which translates audio frequencies into RGB video frequencies. At ten minutes, Colterrain is long enough for its otherwise abstract textures to acquire a life of their own; as the director herself notes, “A line implies action because it is created by a dot moving from one place to another.”

Such narrative qualities were primed by Esther Urlus’ programme opener Chrome, whose genius amplification of the autochrome process (by which the Lumière Brothers coloured their black-and-white photographs in the early 1900s) gives each individual grain unique properties of its own. Watching these grains dance and fizz for nearly eight minutes took me back to childhood, when I’d squeeze my eyes shut and let colour patterns and other apparitions emerge on the inside of my lids.

#43

The film too looks back: Huib Emmer’s soundtrack repurposes a musical piece dating back to the years in which the Lumières were first pioneering cinema. Its title, moreover, conjures chromosomal imagery, and after a while the imagistic texture appears to be comprised of cells fighting to reproduce themselves. This motif carried over to Joost Rekveld’s #43, in which pixels resembling organic cells interact and mutate in accumulatively awesome fashion.

It’s difficult to tell whether such abstract works need to be screened on a vertical screen; what would be lost by showing them in landscape? It has to be said that only a few of these films actually probe verticality. Perhaps the best use of the vertical screen came from Manuel Knapp’s V~, a kind of optical juggernaut in which straight white lines create an intricate grid system on a black screen, from which the vertiginous illusion of a z-axis is formed.

V~

The impact of Björn Kämmerer’s Louver also depends on the height of the image, showing as it does four horizontal tube lights moving from right to left at different speeds, so that one was constantly looking up and down to grasp a sense of the overall pattern.

Billy Roisz and Dieter Kovačič’s Bring Me the Head of Henri Chrétien! similarly makes use of the vertical screen. In it, a widescreen still from Once Upon a Time in the West expands outward until it touches the edges of frame, at which point it explodes into some kind of warped reappropriation. As the original image is forced into a new aspect ratio, its screeching soundtrack seems to scream in protest.

Deorbit

If the curiosity surrounding some of the films’ eligibility for ‘vertical cinema’ was a qualm, though, it was a minor one. At any rate, nobody seemed to mind the programme title during all 17 minutes of Makino Takashi and Telcosystems’ Deorbit, a simply astonishing film whichever way up you look at it.

As it throws all kinds of textures together – hi-hat and cymbal surfaces, water surfaces, static, thumbprints and other blemishes – the film puts one through the grinder, with Balázs Pándi’s drum solo adding a bruised and cosmic rebelliousness to the bronzed and burnt-out palette. To my mind it was the best film of the night – and possibly of IFFR in general. To my besieged ears, it received the heartiest applause.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.