Would you buy a cinema ticket without knowing what you were going to see, or where? Instead of relying on word of mouth, critics or adverts to choose your film, would you happily follow a digital breadcrumb trail of clues via email and website to the surprise venue and film? This odd setup is at the heart of the erstwhile ‘underground’ event that is Secret Cinema.

The Secret Cinema organisation, which launched in December 2007 with screenings of Peter Watkins’ Paranoid Park in a disused South London railway tunnel, and has just finished its biggest edition yet – a month-long screening of an undisclosed first-run blockbuster – actually bases its appeal on two key pillars. There’s the secret-screening element, of course, but what’s on offer extends beyond simple surprise. From those enigmatic, teasing digital missives – designed and worded as if they emanated from within the world of the unspecified movie – until the moment the projector begins, Secret Cinema aims to immerse viewers in the simulated world of the film at hand – reinforcing and extending the ‘fourth wall’ to encompass the entire journey of filmgoing, in a spirit akin to the immersive, interactive theatre experiences that groups like Punchdrunk offer.

My previous Secret Cinema experiences had been based on screenings of The Third Man (in Farringdon’s old Victorian Farmiloe building) and Wings of Desire (inside the closed Pavilion theatre in Shepherd’s Bush). Judging from the clues for this June’s edition, I was due a very different adventure, taking me off-planet rather than to postwar Vienna or Cold War Berlin. Web links directed me towards a swish website of the Brave New Ventures corporation, which urged me as a ‘recruit’ to join the embarkations launching soon on a ‘secret expedition’. Along with the meeting location (you never go directly to the screening venue), you’re also emailed cryptic instructions about appropriate attire: I had to choose my career path from a menu that included ‘Ore Surveyor’, ‘Control Operator’ and ‘Matter Analyst’ – and dress accordingly in what can best be described as a one-piece NASA boiler suit.

The rendezvous was outside the statue of Robert Stephenson at London’s Euston Station. I was directed by clipboard-wielding, sharp-tongued BNV officers into the ‘Control Operator’ line. Bemused commuters looked on at the long rows of boiler-suited recruits blocking their paths to the West Cornwall Pasty Company. But soon we were off, hurried along through the back streets of Euston.

I’d been told to expect the largest Secret Cinema venue to date: 195,000 square feet (an entire city block) in a Euston location which could entertain 900 visitors per screening. The sprawling warehouse seemed epic enough from the outside, and as it turned out the event encompassed the outside grounds too. We were ushered through a series of spaceport booths for registration, currency exchange (earth money was no good where we were going), and finally a decontamination spray-down. From high above us, a BNV officer congratulated us through a megaphone for getting this far, and pumped us up for the voyage ahead. Then my team were whisked off by a hyper-enthusiastic BNV non-commissioned officer inside our space vessel for a briefing on the flight deck.

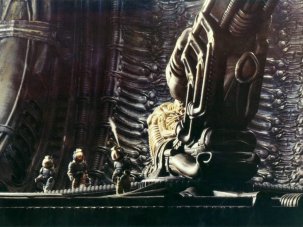

The dark interior was a medley of visual information. Labyrinthine corridors, steep stairwells, futuristic logos, wall-mounted schematics and a kaleidoscope of luminescent light fixtures all conveyed the atmosphere of a run-down space freighter. The cavernous flight deck itself gave a good indication of the different scale of this Secret Cinema, with impressively detailed digital data screens mounted beside actual props from the film, a level of decoration and studio involvement I’d never seen before.

After a quick mission briefing, where we were tasked with grabbing pieces of star maps from around the room, we were left to explore the rest of the vast ship and spend our money tokens. This two-hour pre-screening window is where the immersion factor really kicks in, with a series of mini film sets hosting re-enactments of various segments of the film’s story, and hired actors roping in onlookers. Gradually you lose track of who’s staff and who’s a guest.

After perusing the ship schematics, I came to a white, minimalist, clinical-looking bar boasting rows of fresh lilies hanging from the ceiling. Garishly otherwordly drinks were served by a pair of female androids (or so they seemed). Weighed down with my laptop bag, I took a brief time out in a nearby R&R room, where super-sized beanbags dotted the floor and a screen showed placid images of a lakeside view. Slightly more ominous were a trio of padded ‘psychological behaviour’ rooms, equipped with cameras and floor-mounted mental puzzles, into which I stumbled. They were apparently designed to screen out crew who lacked the stomach for long space voyages.

As I moved from room to room, BNV crew frequently accosted me with little missions (moving boxes from one place to another) or reminded me that physiotherapy sessions were on tap in the exercise rooms. Moving on, I came across further rooms containing a very weird selection of installations – half art, half sci-fi gadgetry – from rows of luminous green tanks to clusters of hanging light tubes that emitted music.

A botany lab I walked into featured a huge table full of potted fauna and forna and an experiment station kitted out with test tubes and pipettes, though a nasty leak from a ceiling pipe soon had the BNV crew taping the area off and warning me of a ‘bio-hazard situation’. All these interactive set pieces were backed by a dense, deep soundtrack of beeps and hums and computerised announcements.

My previous Secret Cinemas had never simply announced the start of the film; audiences were ushered into auditorium as part of the narrative. So it proved here.

Following an announcement from the Captain over the internal comms system that we had exited hyper-sleep and arrived at our destination, it didn’t take long for a bustle of activity and announcements to draw us downstairs to the massive cargo bay, impressively decorated with more prop vehicles from the film.

Then chaos erupted. Officers were thrown through the air onto the parked vehicles; klaxons blazed, hazard lights flashed, and space-suited BNV staff screamed at us to get back to the safety of the escape pod – the auditorium, as it turned out.

Visitors who’d still not guessed that the night’s film was Ridley Scott’s Alien prequel Prometheus were soon given firmer evidence in the form of a short video clip of the gruff director himself there on screen. His appearance, the props from his film, the size of the venue and the fact that Secret Cinema had scored a major Hollywood movie in parallel to its wide release in the UK – all this seemed to be what Secret Cinema’s press team meant when they claimed this as the most ambitious season yet.

Indeed, Secret Cinema can now boast such seriously successful ticket sales – rivalling conventional new-release cinema takings – that one wonders if the term ‘secret’ still applies. After the first week of June, the Guardian’s weekly box-office blog recorded £542,000 in Secret Cinema ticket sales. Secret Cinema’s press office claimed its Prometheus shows had grossed more in pre-sales (£470,000) than the publicised film had at the BFI IMAX (£450,000), from a season offering just one show per weeknight plus matinees on weekends. And they say audience figures continue to rise: 14,000 for The Battle of Algiers in 2011, 20,000 for The Third Man in 2012, and over 25,000 for the Prometheus season.

All this makes for interesting pondering in the light of recent predictions that the box-office boost of 3D cinema is wearing off. It seems filmgoers are prepared to pay a premium (current Secret Cinema tickets are £35) for a 3D experience they can ‘live’ inside. But the inevitable questions are, given the scale and studio-involvement of this Secret Cinema edition: will season 19 top it? And will Hollywood studios be as closely collaborative – or controlling? – in future?

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.