For as long as anyone can remember, the Cambridge Film Festival took place during the four summer months, when this college town turns into the Overlook Hotel. Now embedded in term time, this year’s edition was shorter than usual and all the better for it. Even in its slightly truncated form it was an unmanageably rich feast, with a particularly strong strand of artists’ cinema, and a selection of silent revivals that put the recent London festival in the shade.

20-27 October | UK

The last day’s programme included a world premiere from 1954: the British musical short Harmony Lane, directed by future James Bond helmer Lewis Gilbert in three dimensions, but delayed and released in a measly two. Assembled like a variety show, with turns from the Beverley Sisters, Max Bygraves and a performing dog, it might have served as a structuring metaphor for this festival report, except that the cinematic turns on offer elsewhere around the Cambridge programme were thankfully altogether less redolent of rationing and capital punishment; and their pleasures were not discrete but cumulative, sometimes arising from unexpected connections.

Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s Homo Sapiens (2016) acted as a system reset, zeroing out the familiar cinematic elements of time and movement, and doing away entirely with the infamous mammalian species of the title. What remains is a series of extraordinary images, most of them on the threshold of stillness, of an apparently abandoned world, with a soundtrack of field recordings. One of the eeriest shots, because it raises the question of who is watching, presents the stage of a ruined theatre, with shadows playing against a painted backdrop. Geyrhalter sat next to me – and yes, he did check his phone – so I could have asked how much he’d intervened, digitally or otherwise, in the spaces he had shot. But wouldn’t that spoil the fun?

Anyway I had to dash, to commemorate local lad Syd Barrett, ten years after his death and 50 after his band Pink Floyd made their first recordings. The programme included some deep cuts, such as Kevin Whitney’s Psychedelia (1969), South Kensington’s answer to Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (1966), and a new compilation, Get All That Ant?, by Anthony Stern, a friend of Barrett’s from pre-Floyd days who went on to work with Peter Whitehead. Stern’s San Francisco (1968), which gives the full psychedelic treatment to diary-film footage of his trip out west, and Whitehead’s London 66–67 (1994), a Floyd-heavy remix of Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967), both used early and superior recordings of the band’s Interstellar Overdrive.

San Francisco (1968)

Adam Curtis’s HyperNormalisation recently drew out the historical connections between the San Francisco hippy scene in the 1960s and the tech industry that grew up in the region later, and one wonders whether the same could be done for Cambridge, once home of England’s most psychedelic band, now known (cringe-makingly) as Silicon Fen.

The same counter-culture that produced Pink Floyd half a century ago also produced the London Film-Makers’ Co-op, whose anniversary was celebrated as part of the festival’s microcinema strand. Two of the full-length films chimed intriguingly with Homo Sapiens, being studies of human communities punctuated by long shots of empty spaces. Nina Danino’s Jennifer (2015) is a portrait of a Carmelite nun who has renounced one community and joined another, whose rituals, both spiritual – the marking of the liturgical hours – and domestic, structure the film. We come to know the nunnery, in Ronda, Spain, intimately, but its other inhabitants are known only through sound until the last moment.

Sarah Turner’s Public House (2015/16), newly re-edited, is in part a documentary about the rescue of a South London pub from the grasp of property developers and corporate chains, with a intricately constructed soundtrack of regulars and staff telling the story, retelling anecdotes, and reflecting on the question of what it is to be a ‘regular’ or a ‘local’. No one pretends that the pub’s near-miss with closure and conversion into flats is more than a rearguard action in the continuing scandal of London’s property market. At points the voices begin to stutter and loop, and the regulars go from behaving naturalistically into rituals of their own, and a tap class explodes into movement.

Public House (2015)

Short dance films by Germaine Dulac and Maya Deren, from the 1920s and 40s, had a programme to themselves, probably the most joyous of the festival. (The Syd Barrett evening included a clip of Roger Waters telling a television interviewer that he didn’t want people “jiggling about” at Pink Floyd shows, which explains a lot.) Dancers, as I think Lucia Ruprecht said in a discussion after the film, operate at the limit of the physically possible; film helped them to go beyond it. Within the festival’s broad frame, Deren’s film Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946), nothing but movement, figured as Homo Sapiens’s antipode.

Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946)

Deren’s countryman Alexander Dovzhenko was responsible for one of the most thrilling silents of the festival, Arsenal (1928), a story of the Russian revolution, newly restored and with a terrifically intense soundtrack from Bronnt Industries Kapital. One of the highlights of last year’s CFF was Victor Sjöström’s The Wind, from the same year, made in Hollywood just as the talkies were taking over and just imaginable as a talkie itself. Arsenal isn’t. Moving at montage speed from the realistically reconstructed, sometimes apparently shot handheld, to the flamboyantly symbolic, it too is a film in ‘transfigured time’.

Arsenal (1928)

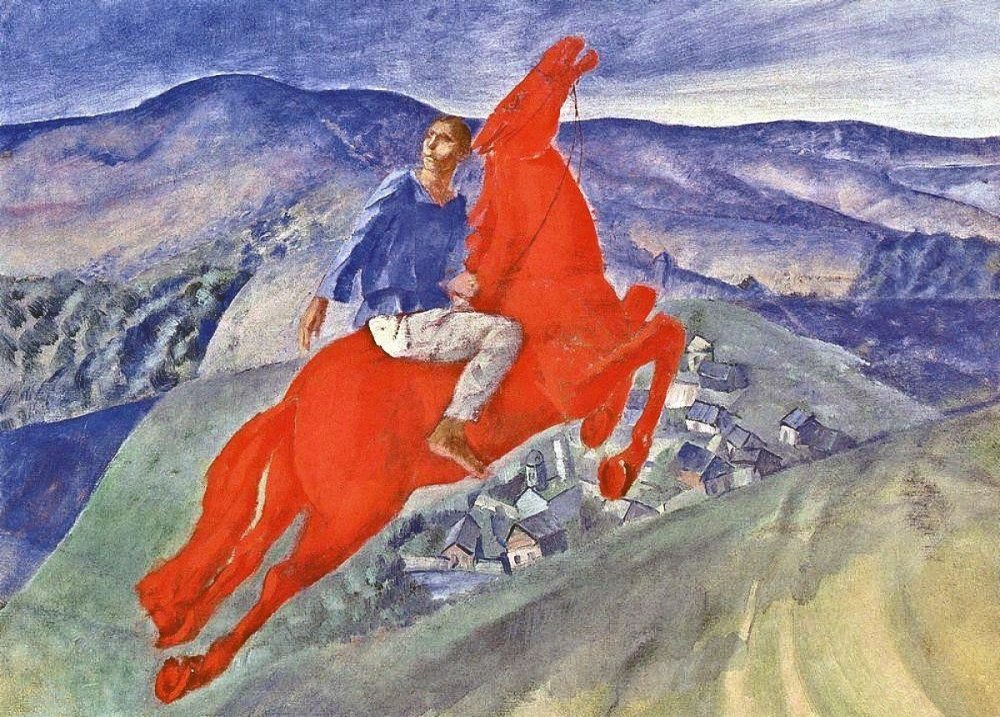

Dovzhenko’s film was shown on the same day as, but not featured in, Revolution: New Art for a New World, a somewhat confusing new documentary by Margy Kinmonth. As the title suggests, this starts out by making a hazardously simple cause-and-effect connection between the revolution and the modernist posters, films, and architecture that followed – only then to leap back and point out that pre-revolutionary Russia was hardly untouched by modernism, and indeed that many modernist artists fled the country during the famine of the early 1920s. (Recall that Maya Deren’s family left in 1922 to escape anti-semitic persecution.)

Revolution: New Art for a New World (2016)

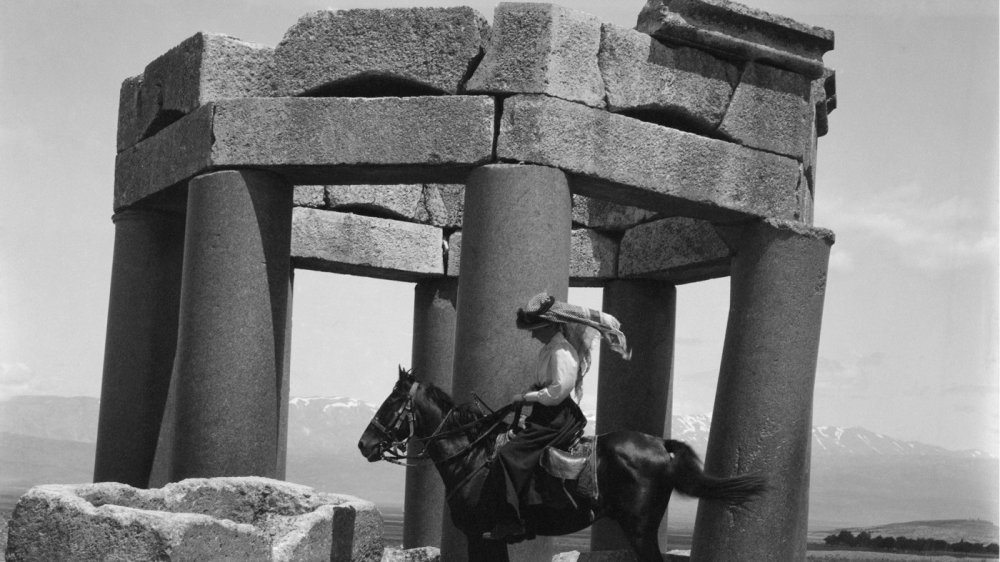

A much more impressive documentary, premiered at London, was Letters from Baghdad, which draws on all kinds of archive material to tell the story of Gertrude Bell, an amateur Arabist who was recruited by British intelligence during the First World War, and took a leading role in the division of the Ottoman Empire after it. Directed by Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum, it is full of portents of the dreadful present, but wise enough not to score cheap points. Bell’s letters, read by Tilda Swinton, demonstrate that the complexities and contradictions of her position were quite apparent to her. As a film making creative use of found footage, and one engaging with the catastrophe in the Middle East, it nicely echoed Sarah Wood’s Boat People (2016), shown as part of the microcinema strand.

Gog (1953)

Harmony Lane was shown as warm-up for Gog (1953), a bit of cheerful sci-fi paranoia from the height of the Cold War, given very few playdates in its intended 3D format at the time, which must have blunted the point of starting the film with a syringe coming at the camera. Apparently the first film to have a computer as its villain, it also features Herbert Marshall, star of Lubitsch’s immortal Trouble in Paradise (1932), wielding a flamethrower. There was nothing else quite like it in the festival, except perhaps Anna Biller’s equally camp and equally colourful The Love Witch (2016), of which we’ll surely hear more.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.