Web exclusive

Graham Cutts’s The Blackguard (1925)

When three reels of The White Shadow (1924) were discovered in New Zealand last summer, the headlines cast unwitting light on the status of British cinema before sound. The Washington Post’s Alfred Hitchcock: His first film, ‘The White Shadow,’ has been found was only the most egregious example of misattribution; but then, even in the country of his birth, few readers could be expected to click on a headline mentioning the film’s credited director, Graham Cutts. Thus the work of the British Silent Film Festival, this year held in Cambridge, is not quite complete, but it has opened up what was once called a ‘lost continent’, putting on screen – and with excellent musical accompaniment – films that hadn’t been seen outside of the BFI’s basement since their first release.

The 11th British Silent Film Festival ran in April 2012 at the Cambridge Arts Picturehouse, UK.

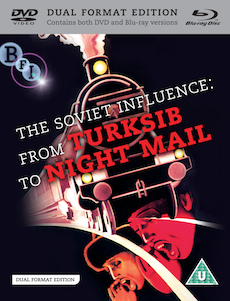

The BFI’s DVD box-set The Soviet Influence: From Turksib to Night Mail, with an essay by Henry K. Miller, is available now. The White Shadow and The Blackguard are available in the BFI’s Mediatheques.

Before the festival’s inauguration in 1998, the consensus, largely inherited from Rachael Low, doyenne of British film historians, was something like this: between the mid 1910s and mid 20s, as Hollywood tightened its grip on the world film market, British producers, their technique hopelessly antediluvian, all but went to the wall. Though the industry was rescued by quota legislation and a round of consolidation, the “contrast between the intellectual appreciation of film assembly by the Russians, and the slow, blind steps by which British studios fumbled their way forward,” as Low wrote in 1971, was “the most depressing aspect of British production.” The exceptions were those like Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Asquith who had been exposed to Soviet films by the Film Society, and Soviet theory by the little magazine Close Up, and who understood that “the greatest development in film technique during the twenties was that of editing”.

As Ian Christie observed in his Rachael Low Lecture, while Low’s history is unsurpassed, her aesthetic criteria, laid down in an era when some of the leading British directors – Thorold Dickinson, Robert Hamer and David Lean – were ex-editors, have since been contested, and the BSFF has in particular championed ‘pastoral’ films like Arthur Rooke’s The Lure of Crooning Water (1920), not entirely dismissed by Low, but described as “rather leisurely”.

The “rather leisurely” English pastoral The Lure of Crooning Water (1920)

This year’s juxtaposition of two terrific Soviet films – Abram Room’s revolutionary The Ghost That Never Returns (1929) and Viktor Turin’s epic Turksib (1929), which unlike the more famous Battleship Potemkin (1925) played at cinemas all over Britain – with the likes of The Bohemian Girl (1922), an exceedingly static and title-heavy Ivor Novello vehicle, would test anyone’s resistance to Low’s ‘Whig interpretation’ of film history. Yet one does not need to disagree with her to find the experience invaluable. After all, much of the work of BSFF favourite Adrian Brunel, director of a series of ‘burlesques’ in the mid-1920s, was devoted to mocking the ‘Sob Stuff’, ‘Sex Stuff’, and ‘Sheikh Stuff’ that comprised such a large proportion of his contemporaries’ output.

The path from The Bohemian Girl to the sophistication of Manning Haynes’s The Ware Case (1928) or Miles Mander’s The First Born (1928) – long championed by BSFF, restored last year and shown this year in Cambridge – is still largely unmapped, and thrilling to tread. It leads not though the Film Society and Close Up, but through comic shorts like Brunel’s, Great War reconstructions and even ordinary narrative feature films. Dickinson became an editor under the tutelage of George Pearson, whose few extant films have been shown in earlier years, Lean under Maurice Elvey, director of Hindle Wakes (1927) among scores of others. Hitchcock, as of 1930, long after he began directing, claimed to have seen only one Soviet film.

One of the most thrilling fragments I saw during the weekend was a battle scene from Sinclair Hill’s The Guns of Loos (1928), Madeleine Carroll’s first film, but also an editor’s tour de force made before the Soviet films arrived here, and indeed before British editors received a screen credit. Another highlight, and a reminder that much of the cinema programme in the 1920s consisted of miscellaneous short items, was the accurately titled Rough Seas Around the British Coast (1929), in which the lashing meted out to a seaside town from sky and sea is intensified by the film’s anonymous cutter.

The Guns of Loos: an “editor’s tour de force”

And then there was Graham Cutts, this year represented by The Blackguard (1925), an Anglo-German co-production shot at the Ufa studios outside Berlin, on which Hitchcock, just as he had on The White Shadow, served as scriptwriter, art director and assistant director. Made about the time of the nadir of production in Britain – the ‘Black November’ of 1924 – it is notably light on intertitles by comparison with its peers back home, shadowy in the manner of German films of the time, and cut with American efficiency, including effective point-of-view shots and reverse angles little in evidence elsewhere at the festival. Cutts should not be written out of the history, but the film passed through Brunel’s post-production workshop on its way to its premiere at the Albert Hall.

Cutts’ first film with Hitchcock, Woman to Woman (1923), remains, like most British films of the 1920s, lost – though only by a few degrees more than all the films that go unseen. Proving that it is possible to do a lot with a little celluloid, Judith McLaren has over the last decade put together an ever more complete reconstruction of Pearson’s Ultus quartet (1915-17), the British answer to Feuillade’s Fantômas serial. The challenge now, according to Ian Christie, is to dig further into the 1910s, from which even less has survived.

Festival director Laraine Porter remarked at one point, rather against the grain of the digital times, that some of the titles BSFF has brought to light in its 15 years are unlikely to be shown again. To venture a paradox, that very poignant feeling brings us closer to the experience of the films’ original viewers, who must have thought the same.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.