As an unapologetic advocate of ‘la politique des auteurs’, seeing individual films as part of a larger body of work is almost second nature to me. At the same time, I have long been attracted to directors whose output amounts to just one feature. There is a compelling mystery about these isolated gestures, referred to by Andrew Sarris as ‘one-shots’, which generate a number of unanswerable questions. What might this artist have achieved under different circumstances? How can we define oeuvres which begin and end concurrently? And, although examples can be found in other countries (Forugh Farrokhzad, André Malraux, Jean Genet, Roddy McDowall, Jeremy Thomas, Hanif Kureishi, Julia Leigh, Richard Flanagan, William Boyd), could there be something peculiarly American about this tendency?

There are many reasons American filmmakers fail to follow up on their debuts, the most obvious being a lack of financial and/or critical success. And these one-offs often seem to foretell their own failure, even evoking it as part of their narratives: the failed bank robbery in Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970), Vic Bealer (Jon Voight)’s failed boxing career in Charles Eastman’s The All-American Boy (1970-1973), the failed attempt to sustain a truce in Frank Sinatra’s None but the Brave (1965), Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum)’s unsuccessful search for the hidden money in Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955), the failed pursuit of the letters in Martin Gabel’s The Lost Moment (1947), Joe Bonham’s (Timothy Bottoms) failed struggle to secure the peace of death in Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun (1971), the failed rescue that ends James Salter’s Three (1969), the noir-inflected atmosphere of inevitable defeat that attends Kyle Niles (Robert Ivers) in James Cagney’s Short Cut to Hell (1957), the arbitrary deaths that conclude Carl Foreman’s The Victors (1963), Christopher Speeth’s Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (1973), and James William Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue (1973), the failures of masculinity in Ernest Lehman’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1972) and Joan Rivers’ Rabbit Test (1977). To which we might add Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (1960), in which the protagonist’s revenge quest is endlessly delayed for reasons even he is unable to satisfactorily explain.

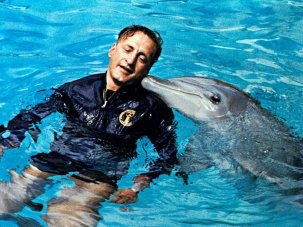

Lilian Gish and Robert Mitchum in Charles Laughton’s sole venture behind the camera Night of the Hunter (1955)

This emphasis on failure sometimes strikes an autobiographical note, the directors of both Wanda and One-Eyed Jacks casting themselves as characters who are repeatedly upbraided for their slowness; the soon-to-be-ex-husband of Loden’s Wanda grumbles about his wife “lying around on the couch”, while an employer tells her she is “just too slow”; similarly, when Brando’s Rio points out that a course of action proposed by Bob Amory (Ben Johnson) is not his style, Amory responds “Maybe you better change it, ’cause your style seems a touch slow to me.” In the context of films whose pace is considerably slower than the norm (and, in the case of One-Eyed Jacks, whose shoot was notoriously protracted), it is as if Loden and Brando are anticipating the complaints that will inevitably be directed towards them, and thus predicting the ‘failure’ of their directorial ambitions.

Yet this sense of failure, of artists reaching out for something that can’t quite be grasped, also exists at a much deeper level. Few of the satisfactions these films provide have anything to do with their being ‘pure’ cinema, many of them privileging aspects of the cinematic apparatus which usually have a strictly subordinate function – graphic design (Saul Bass’s Phase IV, 1974), cinematography (Gordon Willis’s Windows, 1980), screenwriting (The Victors, with its lengthy, self-contained scenes), the production process (Philip D’Antoni’s The Seven-Ups, 1973) – or import approaches that originate elsewhere: music (David Byrne’s True Stories, 1986), stand-up comedy (Rabbit Test), theatre (Harold Clurman’s Deadline at Dawn, 1946), literature (The Lost Moment), choreography (Patricia Birch’s Grease 2, 1982) and the fairground (Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood; Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls, 1962).

Robert Cummings and Susan Hayward in Martin Gabel’s The Lost Moment (1947)

The one thing all these texts have in common is that they seldom refer to anything beyond themselves. Several, including such otherwise very different works as Deadline at Dawn and Eddie Murphy’s Harlem Nights (1989), use studio sets as closed worlds whose artificiality is underlined. The Lost Moment is a particularly striking example of this, its stress on closed spaces within closed spaces (even the apparent exteriors are simply one more ‘room’) supporting a narrative in which the present is enclosed within the past (or vice versa). This is a labyrinth which can neither be escaped nor meaningfully extended, and although the result is masterful, it is easy enough to see why Gabel never returned to the director’s chair.

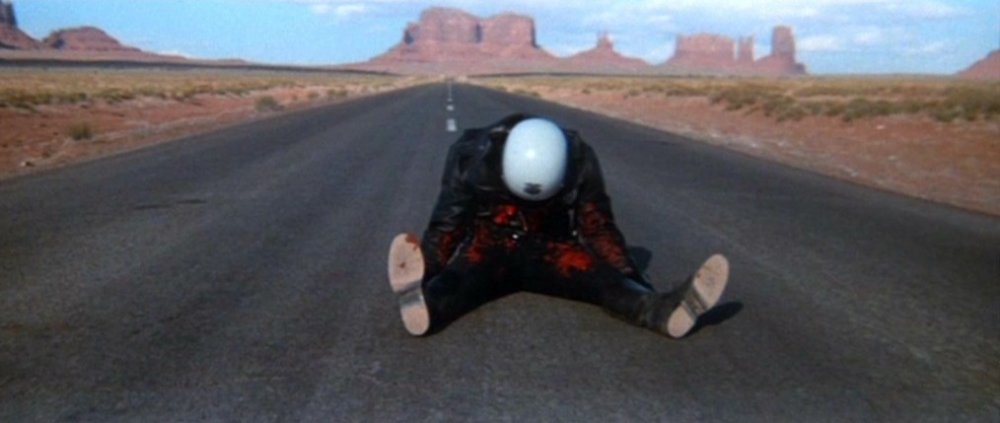

Indeed, the majority of these films adopt stylistic practices which are not susceptible to further development, and can ultimately do nothing except close in on themselves. Most of the previously mentioned titles fit neatly into this category, and thus feel right at home alongside Walter Matthau’s Gangster Story (1959), S. Lee Pogostin’s Hard Contract (1969), Leonard Kastle’s The Honeymoon Killers (1969), Michael Barry’s The Second Coming of Suzanne (1973), Walter Murch’s Return to Oz (1985), Stephen King’s Maximum Overdrive (1986) and Ryan Gosling’s Lost River (2013). One-off auteurs generally favour aesthetics which are self-devouring, consuming narrative, film and filmmaker in a single gesture. The defining moment here is the final shot of Electra Glide in Blue, during which the camera pulls back from a dying Robert Blake and spends several minutes moving slowly down an empty highway, as if James William Guercio were watching his new career vanish into the distance.

The ending of James William Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue (1973)

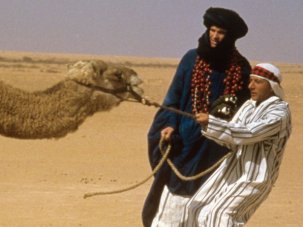

One-Eyed Jacks is, as its title implies, the joker in this particular pack, simultaneously opening up and shutting down its world, displaying large swaths of landscape while focusing ever more relentlessly on the Oedipal conflict between Rio and Dad Longworth (Karl Malden), then closing in even further on Rio, whose internal struggle ends up subsuming everything – landscapes, narrative progress, even Brando’s directorial vocation. As so often with Brando’s performances, opening up might actually be a form of shutting down, an emphasis on unrestrained emotion and spontaneous revelation merely the cover beneath which more private truths can be concealed.

If One-Eyed Jacks collapses into the black hole of its lead actor’s persona, None but the Brave – whose island location is every bit as sheltered as the studio settings of Gabel, Clurman and Murphy – does precisely the opposite, constantly spinning away from Sinatra’s on-screen presence. Its didactic intercutting between Japanese and American soldiers actually disguises a much stranger pattern, functioning as a sleight of hand which enables Sinatra to integrate himself into various groups, slip into the background of the frame, or disappear completely.

Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (1960)

This sounds superficially similar to Clint Eastwood’s approach, but it really isn’t. Eastwood is interested in probing his star image, seeing what happens when it comes into conflict with less hierarchical forms of organisation. What Sinatra does is both more extreme and more ‘exhausting’; he seems to be wishing his image away, hoping that it (like his freshly assumed role as director) will evaporate before the film has played out. Which ensures that None but the Brave has something in common with another one-off by a singer, Bob Dylan’s Renaldo & Clara (1977), but also ends up bringing Sinatra into the same orbit of failure as Brando, the two directors arriving at identical destinations by diametrically opposed routes.

Brando claimed to regard acting as an essentially frivolous activity, an assumption fully supported by One-Eyed Jacks. Rio calculatedly acquires ‘props’ (the ring he steals during the opening robbery, the necklace he acquires during a carnival) intended for use in acts of seduction. The way he casually abandons the role, that of a passionate lover, he is playing when trouble arises (he brutally pulls the ring off the finger of the woman he had been seducing, cynically adding “Maybe next time”) suggests he considers performance to be fundamentally inconsequential, something which can be put on and taken off at will. Rio’s offhand attitude towards performance and the responsibilities it engenders is reflected in his betrayal by a father figure whose similarly cavalier behaviour plunges Rio into a state of stasis from which neither he nor the film is capable of emerging. Since many of them were directed by actors, it is hardly surprising that several of these ‘one-shots’ share One-Eyed Jacks’ emphasis on the relationship between familial dynamics and the problematic nature of performing.

In Hide in Plain Sight (1980), James Caan casts himself as a blue-collar worker who prefers to shy away from public exposure, yet cannot reconstruct his lost family until he learns to perform more effectively in the worlds of courtroom and media; while the protagonist of Johnny Depp’s The Brave (1997) is an impoverished Native American who, in order to secure money for his family, agrees to ‘star’ in a snuff film whose ‘metteur-en-scène’ is played by the director of One-Eyed Jacks. This emphasis is even discernible when the filmmakers remain offscreen; The Night of the Hunter focuses on a boy who is torn between two fathers offering him theoretically opposed yet oddly complementary performative models (and who eventually chooses to align himself with a mother figure).

Johnny Depp in his self-directed The Brave (1997)

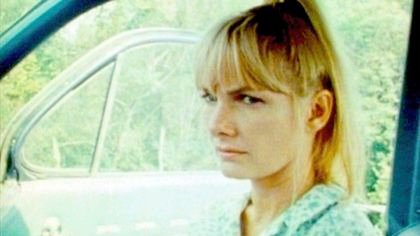

But it is Wanda that now seems the richest of these works, the one whose failure, despite being foretold, might be redefined as a form of victory. For Wanda is a film in which everything is backwards, the person shaping the mise en scène from behind the camera appearing onscreen as a character continually being ‘directed’ by others. The eponymous, and aptly named, protagonist ‘wanders’ into a life of crime simply because she lacks the assertiveness which would enable her to resist the commands of Mr Dennis (Michael Higgins), an unprepossessing example of masculinity (a newspaper report describes him as “the kind you wouldn’t notice”) who acts as if he were James Stewart in Vertigo (1958), comically making over Wanda’s appearance.

Yet, in the context of an American cinema dominated by controlling men, reticence might be a positive rather than negative factor, a protest against those arrogant ways of knowing proffered as unquestionable norms by mainstream Hollywood (the notion of treating life as a series of consequence-free improvisations is clearly far less attractive for Loden than it was for Brando). The closing scene shows Wanda partying with some people she has met by chance. Are we to see her as finally having (however tentatively) been absorbed into a non-oppressive community where men and women treat each other as equals, or is this an entirely random conclusion, indicating that Wanda will continue drifting from one meaningless encounter to another?

Wanda (1970)

Similarly, does the scene in which Wanda visits a cinema where a Mexican musical is showing suggest she is ‘closed’ (so undiscriminating that she will watch anything) or ‘open’ (receptive to the products of foreign cultures)? Loden’s refusal to answer these questions, to impose meaning, to provide a definitive sense of closure, undoubtedly explains why Wanda received only the most cursory distribution, preventing its creator from financing any more features (though she made two splendid shorts for television before dying at a tragically early age in 1980).

Yet it is also what makes this film so enticing. Unlike One-Eyed Jacks’s Rio, Wanda cannot overshadow those landscapes through which she moves, her habit of tentatively entering shots as if uncertain that she has any right to inhabit this visual field (Elaine May does something similar in her first feature A New Leaf, made the same year) speaking eloquently of Loden’s position as a female director in an industry where directing was an almost exclusively male prerogative.

Michael Higgins with Barbara Loden in Wanda

It is hardly surprising that Loden has frequently been cited as an influence by actresses and female filmmakers (Marguerite Duras, Isabelle Huppert, Kelly Reichardt, Pia Marais, Valeska Grisebach, Rita Azevedo Gomes, Christine Molloy ). For unlike most one-offs, Wanda is about opening up rather than closing down, providing a model to emulate rather than a dead end to avoid. Failure is inscribed here not as it is for those directors uninterested in following up their sophomore efforts, but rather in the manner of an artist who passionately desires to create a larger oeuvre (Loden hoped to film Kate Chopin’s The Awakening), but knows full well that no such thing will be possible. It is a failure, in other words, that draws our attention to, and radically opposes, those circumstances mediating against its success.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.