Much criticism involves making sense of one film by juxtaposing it with another, the choice of comparison usually being determined by the critic’s specific interests. An auteurist may well consider Rio Bravo (1958) alongside other films directed by Howard Hawks, such as Bringing Up Baby (1938), whereas the genre specialist might prefer looking at it in the context other westerns – such as High Noon (1952), which specifically provided Hawks with his point of departure – and commentators interested in star images will inevitably focus on other John Wayne vehicles, such as Sands of Iwo Jima (1949). But illuminating juxtapositions sometimes come about entirely by chance, being determined less by a deliberate search for works likely to furnish evidence supporting a theory than by the realisation that one has encountered correspondences where they are least expected.

Unless our viewing is entirely systematic (and who can really boast of this?), many of our cinematic experiences will be determined by factors we had not allowed for. My initial (and, to a large extent, subsequent) opinion of Michael Mann’s Heat (1995) would undoubtedly have been more favourable were it not for the fact that the evening before going to see it I had watched a VHS tape of James B. Harris’s Boiling Point (1993), a thriller which shares Mann’s fascination with the continuity between cops and criminals, but does so not in the semi-mythic style of Heat, whose every thematic statement is sharply underlined, but rather in the manner of an unpretentious B programmer (running 92 rather than 170 minutes), in which points are made neatly and concisely, the focus being on the barely competent (on both sides of the law) rather than the admirably professional. If Heat, for all its undoubted qualities, might legitimately be described as overblown or pretentious, these are terms which could not, by any stretch of the imagination, be applied to Boiling Point.

Q & A (1990)

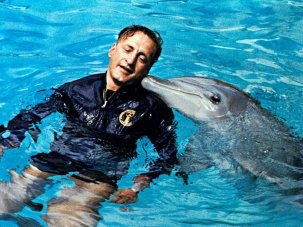

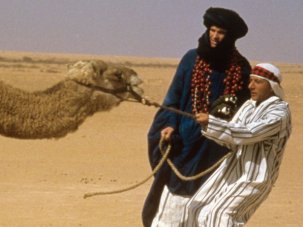

Of course, Heat and Boiling Point (note the interchangeable titles) belong to the same genre, making this comparison relatively commonplace. But consider the similarities between Sidney Lumet’s Q & A (1990) – an American crime drama in which the killing by New York police officer Mike Brennan (Nick Nolte) of a Latino hoodlum is investigated by Assistant District Attorney Al Reilly (Timothy Hutton), who gradually uncovers a tangled web of corruption – and Otomo Katsuhiro’s Akira (1987), a post-apocalyptic Japanese anime set in the neo-Tokyo of 2019, in which teenage biker Tetsuo demonstrates psychic powers linking him to the mysterious Akira, who may have been responsible for a nuclear explosion that destroyed Tokyo three decades earlier.

On the face of it, these films have little in common beyond an emphasis on the infernal city (a trope borrowed from noir), and it was only thanks to a quirk of distribution – which led to Akira receiving its belated UK theatrical release in January 1991, just a few weeks before Q & A opened – that I happened to encounter them at around the same time, and note their structural similarities. This resemblance seemed all the more consequential since the structure of Akira, which I viewed first, was so unusual.

Akira (1987)

Tony Rayns described this aspect well in his Monthly Film Bulletin (March 1991) review: “(Akira) starts out embroiled in a feud between pill-popping delinquent bikers, broadens to take in terrorist guerrillas, demented scientists and a military coup, and winds up envisaging the birth of a new universe. This ‘exploding’ structure would seem unprecedented if it were not for King Hu’s equally singular A Touch of Zen, which also expanded its frame of reference from the domestic to the political to the cosmic.”

What immediately struck me about Q & A when I saw it soon afterwards was that, like Akira, it made use of the ‘exploding’ structure described by Rayns. Both films start with seemingly quotidian acts of violence – fights between rival street gangs, a police officer casually executing a hoodlum – but subsequently expand their frames of reference in virtually every scene, resulting in narratives so complex they are almost impossible to follow on first viewing.

Otomo’s film, with its final embrace of the act of creation, is clearly more extreme in this respect, but Lumet’s comes surprisingly close to matching it, the murder with which it begins being merely the opening statement in an argument that shoots off in several overlapping directions simultaneously, tackling questions of politics – the corrupt DA, Kevin Quinn (Patrick O’Neal), has his eye on the White House – geography (characters move from one country to another in the space of a single cut), time (the roots of the killing are traced to events that occurred when the protagonists were in their teens, just as Reilly’s investigation is compromised by the fact that he was once romantically involved with the current partner of one of the individuals involved), and even gender: Brennan’s crude machismo becomes increasingly theatrical, and is eventually absorbed into a world of transvestite stage performers (who play at femininity much as Brennan plays at masculinity), ensuring that the line between male and female is as confused as the one between the forces of law and various criminal underworlds, or between the world of the street and the world of international politics.

Q & A (1990)

Once one grasps the structural resemblance between these two superficially disparate works, it is surprising how many of the smaller details start to align. The gang fights that introduce Akira might illustrate those unseen events Q & A’s conspirators are attempting to conceal, reveal, or use as bargaining chips: Quinn’s youthful activities as an exceptionally violent member of a street gang. Both films involve protagonists who discover hidden aspects of themselves (Tetsuo’s psychic powers, Reilly’s racism). In both narratives, a climactic orgy of destruction precedes a final suggestion of renewal or rebirth (though Reilly’s exists strictly on the personal level).

Even the introductory images provide a curious echo, Akira beginning (after a prologue explicating the historical background) with a shot of a flickering neon sign, just as Q & A begins with a close-up of a traffic light changing from red to green. Large-scale structures thus proceed outwards from images focusing on peripheral aspects of the decor, Quinn’s complaint that Reilly has taken a simple case and complicated it suggesting the principle around which these films are constructed.

Akira (1987)

Q & A (1990)

Would it have occurred to me to couple Akira and Q&A if I hadn’t seen them in such close proximity? Perhaps not. But this doesn’t render the link gratuitous. These films, already so rich individually, seem much richer when considered in tandem, readings which take note of their similarities potentially illuminating areas which would otherwise have remained obscure. One way or another, context is everything.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.