The first thing we see is a Hollywood studio recreation, circa 1946, of a Paris street, circa 1880. A female singer is performing My Bel Ami, a popular song about a philanderer. A woman, Rachel Michot (Marie Wilson), sitting outside a cafe named Desir, extracts some money from her purse and purchases a lyric sheet from the singer.

While this is happening, a man named Georges Duroy, whom we will recognise as George Sanders, advances from the background of the frame, passing the singer and her customer just as their transaction is taking place. Holding up one of the lyric sheets, Rachel turns to regard the man walking past her. The realisation that he is being stared at brings Duroy to a halt, motivating a cut to him looking at Rachel with an expression of surprise and disturbance. The resulting composition juxtaposes Duroy with the cover of the lyric sheet, which displays what might easily be a caricature of his face. The following shot shows Rachel scrutinising Duroy with unconcealed desire.

This is the opening scene of Albert Lewin’s The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1946), an adaptation of Guy de Maupassant’s Bel Ami, which relates, in the words of an introductory title, “The history of a scoundrel”, a seducer who exploits women in order to further his ambitions, heartlessly discarding them once they cease to be of use. Duroy will later insist (in a speech derived from Théophile Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin) that “A woman has an obvious advantage over a statue; she turns herself in the direction you desire, whilst a statue you have to walk around it to get the right point of view, and that is tiring.”

Yet our introduction to this character has him trapped by a controlling female gaze, reduced to the level of a sexual object under the sign of ‘desire’. This movement between looking and being looked at structures Lewin’s remarkable film (in which a blind man represents the voice of morality), having seeped into its mise en scène; several interiors are dominated by eye-like windows, from whose gaze none of the characters, male or female, can escape.

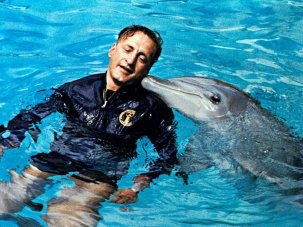

Angela Lansbury and George Sanders in The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1946)

As a reliable producer at MGM, Lewin enjoyed a harmonious relationship with the studio system, turning out such popular titles as Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and The Good Earth (1937). The six films he directed between 1942 and 1957, however, feel like the creations of a Welles or Von Stroheim, an uncompromising maverick functioning entirely on his own terms within a commercial framework. While the overtly surrealist Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951) has attracted a cult following, it is the trilogy starring George Sanders – beginning with The Moon and Sixpence (1942) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) – upon which claims for Lewin’s importance inevitably focus.

If The Private Affairs of Bel Ami now seems the most modern of these films, this is in large part due to its feminist concerns. The emphasis throughout is on women’s oppression under patriarchy: Clotilde (Angela Lansbury) complains that nobody will take an unmarried woman dancing, and tells Duroy she would like to dress up “as a young man in a full dress suit” (recalling Lewin’s unrealised plan to cast Greta Garbo as Dorian Gray).

Yet such expressions of female emancipation rub shoulders with a dark view of male sexuality, which suggests precisely why Clotilde’s desires must remain unfulfilled. Gender divisions are the cement holding the bricks of this world together, and if women can be reduced to objects, men are by no means better off, since they are reduced to penises. Duroy is the very model of the phallic male, smoking cigars, wielding guns and canes, manipulating writing instruments in a masturbatory manner, pitching cards into a hat, and playing with a toy that consists of a ball attached to a wooden stick by a piece of string, the game being to manipulate the ball into a hole at the top of the stick (the winner is whoever succeeds in doing this the greatest number of times). There could hardly be a more apt image for Duroy’s sexuality; his amatory encounters, far from providing him with any satisfaction, are a series of mechanical tasks that must be repeated over and over again, with no payoff except the knowledge that he has won rather than lost.

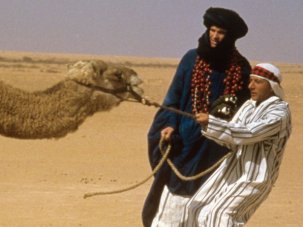

The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1946)

But the key motif is initiated when Duroy encounters his old friend Charles Forestier (John Carradine), and explains that he has fallen on hard times. Pulling a Punch and Judy puppet from his pocket, Duroy confesses to having “squandered the price of a breakfast on this toy that is quite inedible… It occurred to me that I have need of a stout stick like that of Punch to beat my way.” When Forestier, who describes the toy as “Punch and his stick” (thus entirely removing Judy from the equation), subsequently watches Duroy humiliate Rachel, he observes “You’re very successful with women. You must look after that. It might lead to something. In Paris it’s through them one gets on most quickly”. At this point, Lewin cuts to a close-up of Duroy staring intensely at the puppet while repeating his earlier line: “A stick like that of Punch”. The implication is unmistakable; it is Duroy’s penis that will serve as the “stout stick” he needs to beat his way.

The controlling gaze and the aggressive phallus will thus be the instruments Duroy uses to assert his patriarchal privilege, elevating him from his ‘feminine’ position of helplessness to the heights of ‘masculine’ power. In one of the film’s most striking moments, he brings a dinner party conversation to an abrupt halt by declaring “What strikes me most about Punch is his amorous inclination”, a statement followed by individual close-ups of the five women present, who stare at Duroy with expressions ranging from shock to implicitly sexual curiosity.

The Punch motif does not derive from de Maupassant, whose protagonist is last seen enjoying the fruits of his success. Lewin, obeying both the logic of his own structure and the demands of a production code which insists evildoers be punished, ends The Private Affairs of Bel Ami with Duroy being killed by the man whose title he had stolen. The fatal duel takes place near a puppet theatre on which a painting of Punch beating Judy over the head with his strikingly phallic stick is visible, and it is this theatre Lewin tracks in to during the closing shot, making explicit a connection the film has hinted at throughout its running time – that between phallocentric masculinity and death.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.