I first saw Mike Nichols’ The Day of the Dolphin (1973) when it was shown, panned-and-scanned, on BBC1 in the 1980s. I liked it well enough, but ultimately considered it a failure. Yet, when I watched the film again recently in its correct 2.35:1 ratio, it appeared far more successful. Indeed, those elements I had previously dismissed as hopelessly flawed were precisely the ones that now seemed especially fascinating. I strongly suspect it was the BBC’s cropping of the Panavision frame that initially prevented me from noticing that The Day of the Dolphin was centrally concerned with cinema itself, with the ways in which narratives both define and confine images.

The Day of the Dolphin is available in the UK on DVD.

Nichols’ film – loosely adapted by Buck Henry from Robert Merle’s 1967 novel Un animal doué de raison (An Animal Endowed with Reason) – focuses on marine biologist Jake Terrell (George C. Scott), who, together with his wife Maggie (Trish Van Devere) and a small team of collaborators, is researching dolphin behaviour on an isolated island. At the insistence of his financiers, the Franklin Foundation, Terrell is obliged to give a journalist named Mahoney (Paul Sorvino) access to his facilities. When Terrell’s trained dolphins are kidnapped, Mahoney reveals that he is actually a government agent who has uncovered the foundation’s scheme to have the dolphins blow up a boat carrying America’s president.

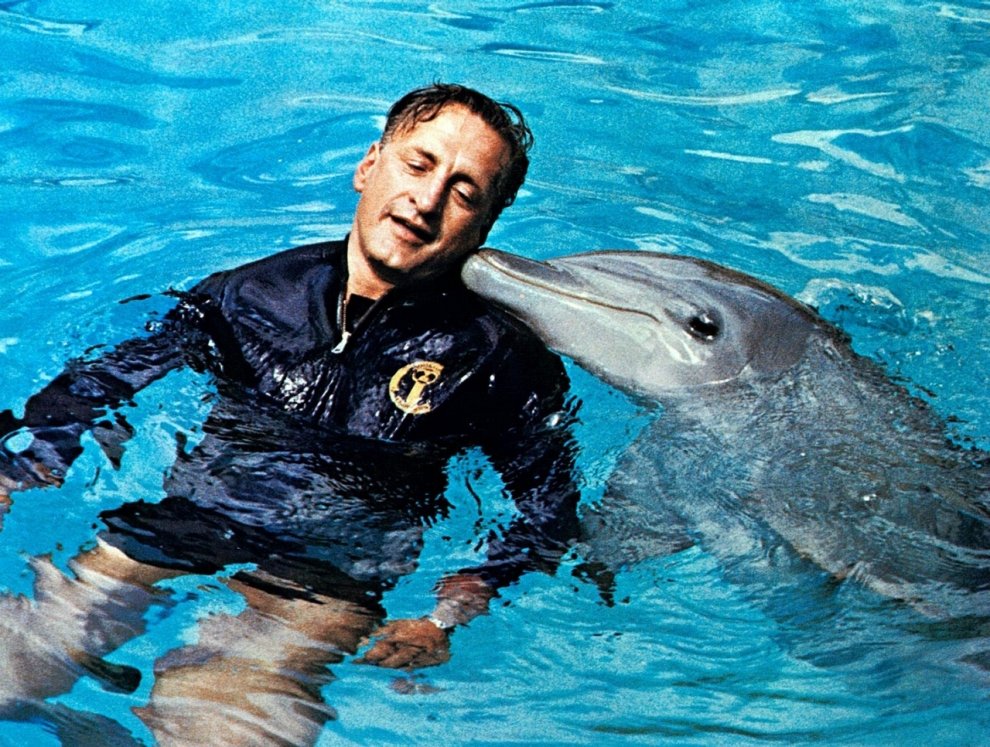

The thematic importance of seeing is immediately established by The Day of the Dolphin’s opening credits, which play over an image emphasising the eyes of a dolphin. We then see Dr Terrell, in close-up against a black background, speaking directly to the camera as he delivers a lecture on dolphins, intercut with shots of these animals demonstrating their skills.

This lecture continues for five minutes before Terrell, though still addressing the camera (“Now watch closely, because this happens rather quickly”), moves towards the right of the frame, allowing the left to be dominated by a screen on which footage of a dolphin giving birth is being projected. Only after the lights are turned on do we discover that Terrell has been making a speech to an audience which consists almost entirely of women.

The Day of the Dolphin (1973)

Up to this point, we might easily have assumed we were watching a documentary about dolphins hosted by George C. Scott. And our impression that The Day of the Dolphin exists somewhere in the gap between fiction and documentary persists for much of the film’s first hour, large sections of which are devoted to simply observing dolphins interacting with Terrell’s team.

It is only later that a scheme to assassinate the president starts dominating the narrative. Several critics have seen this as a major flaw, with even a writer as sympathetic towards Nichols as Richard Combs complaining that “Its first half is a brilliant treatment of inner things… which turns in the second half into unthinking movie action… allowing no theatrical ambiguity or corresponding mystery” (Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1989).

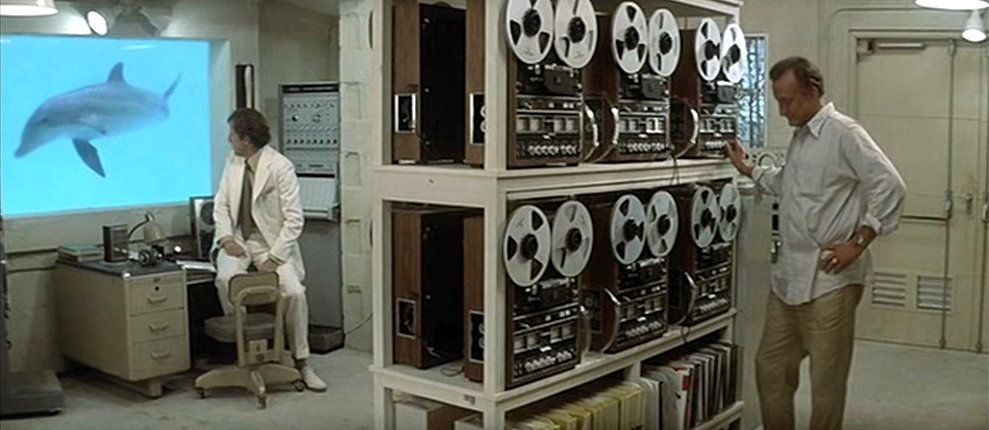

I would argue that, far from being a flaw, this turn exists at the heart of a work which can be seen as Mike Nichols’ emotional autobiography. When Harold DeMilo (Fritz Weaver), chief executive of the Franklin Foundation, first visits the island, Terrell takes him to a room containing a window through which a tank is visible. As DeMilo watches dolphins swimming past the window, Terrell turns on a series of reel-to-reel tapes which contain recordings of the animals speaking. Terrell here becomes Nichols’ stand-in, a metteur en scène manipulating the soundtrack while his audience contemplates a ‘screen’ in the background.

The Day of the Dolphin (1973)

There is a parallel here with John Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), in which Cosmo Vittelli (Ben Gazzara)’s attempts to run a nightclub embodying his notions of stylish sophistication are foiled by mobsters who demand he repay his debt to them by carrying out the eponymous murder. These underworld figures recall the Hollywood financiers who, having little time for Cassavetes’ actor-based aesthetic, insisted that details of performance and character be subordinated to strictly narrative (which is to say commercial) concerns.

The Day of the Dolphin works in much the same way, the Franklin Foundation’s intrusion on Terrell’s island strikingly anticipating the Mob’s unwelcome visits to Cosmo’s club (island and club both representing cinematic ideals). When the five male foundation executives make their first appearance, Nichols spreads them across the widescreen frame as they interrogate Terrell, emphasising the thoroughness with which they have usurped a visual field previously dedicated to more ‘fluid’ matters. The resulting shots of an all-male group listening to and questioning Terrell inevitably recall, and contrast with, that predominantly female audience attending the opening lecture. If the film’s documentary ambitions are associated with a female viewership, its plot-driven sections are observed by a male audience whose requirements are quite different.

The Day of the Dolphin (1973)

It is in this context that Mahoney’s function becomes clear. He is introduced into the story proper (after being seen as an onlooker during the introductory dolphin footage) at the end of Terrell’s initial lecture. As the last woman to ask a question leans back, we see Mahoney sitting behind her, obviously out of place amidst this female assembly. An aura of menace surrounds him during the earlier part of the film, particularly when we see him blackmailing DeMilo.

As details of the assassination scheme emerge, however, Mahoney is suddenly revealed to be on Terrell’s side. Yet Nichols’ point is surely that our initial impressions were correct (and the fact that Paul Sorvino later became known for playing Mafiosi makes this even clearer). Mahoney may ostensibly stand with the forces of ‘good’ rather than ‘evil’, but, like Cassavetes’ gangsters, he nonetheless speaks for that milieu of profit-oriented moviemaking which demands Nichols/Terrell stop playing his ‘feminine’ ecological/documentary/anti-narrative games, and get on with the serious ‘masculine’ business of telling a thrilling story involving heroes triumphant and villains defeated. As he tells Terrell, “I always thought you work for the people that pay you.”

The Day of the Dolphin (1973)

The Day of the Dolphin has a surprising amount in common with Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 (1971). In both films, relaxed observation of communal activity gradually gives way to a plot which involves a political conspiracy, and is notable more for disrupting the documentary strands than for anything it achieves in terms of narrative development.

Which is to say that, for Nichols and Rivette, the resolution fails to satisfy not because the auteurs’ intentions have failed to cohere, but because they have been magnificently accomplished, the feeling of discontent these films leave us with being precisely their point. The frustrations conveyed by both directors relate to their views regarding a form of cinema which is not possible, and Nichols concludes The Day of the Dolphin with a shot which perfectly sums up this concern; as Terrell and his wife contemplate the failure of their communal enterprise, the image fades not to the more traditional black, but rather to a blinding white – the white of a cinema screen upon which nothing is being projected.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.