Reviewing Drafthouse’s Blu-ray of Wake in Fright (1971) for Sight & Sound (May 2013), Michael Atkinson describes Ted Kotcheff’s film as “a wrenchingly odd piece of work… that could’ve easily, with some tweaks, emerged as a dark comedy”. When I finally caught up with this remarkable film, what immediately struck me was how closely it anticipated an actual black comedy: Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985). Another of those chance juxtapositions I described in last month’s column? Perhaps. Then again, perhaps not. For Scorsese was one of Wake in Fright’s earliest champions; after selecting it as a Cannes Classic in 2009, he described the film as “a deeply – and I mean deeply – unsettling and disturbing movie. I saw it when it premiered at Cannes in 1971 and it left me speechless.”

It is easy enough to see how the director of Who’s That Knocking at My Door (1968), with its violently ritualised male camaraderie, would have recognised a kindred spirit here. Indeed, traces of Wake in Fright can be found in several of Scorsese’s later films: an overhead shot of coins being tossed in the air during a gambling sequence is recreated in Casino (1995), while, as Adrian Martin notes in his booklet essay for Masters of Cinema’s disc, the students in the opening scene “have the same slack-jawed, rather moronic look that Martin Scorsese gives to a gaggle of New Zealanders at the end of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)”.

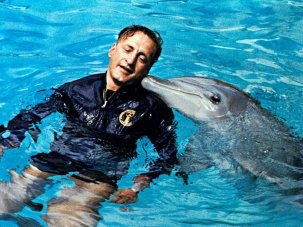

After Hours (1985)

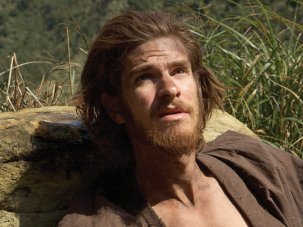

Yet Wake in Fright’s influence on After Hours goes well beyond isolated moments, the resemblances between these films being so extensive that a single plot synopsis might suffice for both.

1 The protagonist is initially encountered teaching. Wake in Fright’s John Grant (Gary Bond) is first seen sitting silently before an equally silent group of children in an isolated Australian school, all of them eager for the Christmas vacation to begin. After Hours’ Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) is introduced showing an employee in his New York firm how to program a computer.

2 The protagonist undertakes a journey which he hopes will culminate in a sexual encounter. Grant sets out for Sydney, where he intends to spend Christmas with his girlfriend. Hackett takes a taxi to Soho for a date with Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), whom he recently met in a coffee shop.

3 The protagonist loses his money. Grant gambles away his cash during a stopover in the mining town Bundanyabba, while Hackett’s 20-dollar bill flies out the window of the taxi. As a result, these characters find themselves stranded in nightmarish worlds where the usual rules of society no longer apply, worlds marked by the presence of sexually assertive women, exclusive clubs, and suicides.

4 After failing to escape, the protagonist is reduced to a state of immobility. Grant spends several weeks in a hospital bed after shooting himself, while Hackett is sealed inside a statue.

5 The protagonist is finally returned to his point of departure, a little the worse for wear, but essentially unchanged by his experiences.

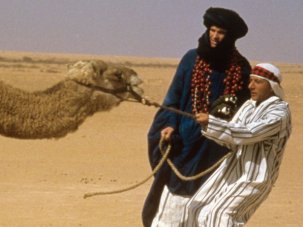

Wake in Fright (1971)

Writing about After Hours in CineAction 6 (Fall 1986), Robin Wood describes it as “a male nightmare… the nightmare of a world in which the Father no longer presides, in which nothing is any longer in its ‘correct’ place: hence the film’s emphasis on independent women and gay men. It is a world in which the protagonist (through whose eyes we see it) – a ‘son’ totally subject to the ‘Father’ of corporate capitalism – can find no position to occupy and with which he cannot cope”.

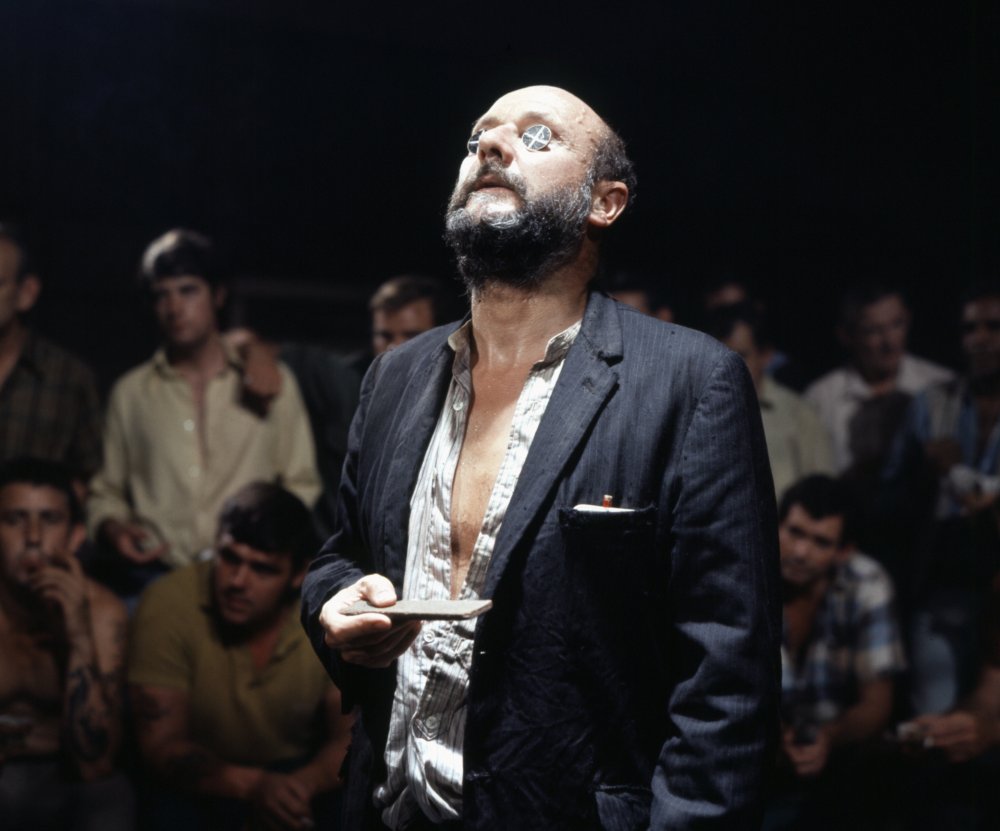

Wood’s remarks are equally relevant to Wake in Fright, whose father figures – local police officer Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty) and Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasence) – are complicit in the general corruption. This leaves the men (who vastly outnumber the women) of this community free to engage in egregiously childlike behaviour, it being one of the film’s nicest ironies that the children in the opening sequence act far more maturely than any of the adults (one of them hilariously asks Grant to “Give my love to your girlfriend in Sydney”).

After Hours (1985)

Those proudly gay individuals who appear in After Hours may be distinguished by their absence from Wake in Fright, but Kotcheff’s film is nonetheless steeped in homosexuality, something reinforced rather than diluted by the presence of women determined to satisfy their own physical desires rather than cater for the needs of men: the hotel receptionist more interested in cooling herself with a fan and some ice water than in helping Grant find his room; and Janette Hynes (Kotcheff’s then wife Sylvia Kay), whose insistence on sleeping with Grant causes him to vomit. The casting of the gay actor Gary Bond gives added resonance to this encounter, as well as to the hints that Grant’s sexual identity is more fluid than it might appear. He carries a photograph of Robyn, his girlfriend in Sydney, and dreams about her during his journey to Bundanyabba, but there is little reason to believe she actually exists. When Janette’s father proposes Grant replace the money he lost by putting through a call to Sydney, Grant insists “There’s no one there I could borrow money from,” and Janette’s curious reaction (accentuated by a close-up of her looking highly dubious) when Grant talks about his girlfriend alerts us to the possibility that Robyn is an elaborate fantasy.

Wake in Fright (1971)

It is here that the emphasis on castration in After Hours and Wake in Fright assumes its full meaning. Hackett discovers some bathroom graffiti depicting a shark biting a man’s penis, gets his hand caught in Julie’s (Teri Garr) hair, and has his head partially shaved after entering a club on Mohawk Night. Wake in Fright’s main reference to castration is far less oblique; Grant participates in a kangaroo hunt during which one of the slaughtered animals has its testicles removed (“Doc eats ’em. Reckon they’re the best part of the ’roo”). The castration motif in both the Scorsese and the Kotcheff is clearly related to the central characters’ loss of money – for in a capitalist society, being without money is analogous to being impotent (the frequent exchanges of keys in these films have their own carnal undercurrents). But Kotcheff goes further in suggesting his hero’s actions are motivated by barely suppressed homosexual desires, even implying that Grant has sex with Doc (interestingly, these intimations of homosexuality, as well as the scene depicting Grant’s sexual failure with Janette, were removed from the version distributed on VHS in the 80s under the title Outback).

After Hours (1985)

These films cast wide cinematic nets. Aside from anticipating Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973) and John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), Wake in Fright resembles several titles with which it was more or less contemporary; Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972), Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), and Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1970), another Australian classic by a visiting director which moves from schoolroom to wilderness. After Hours belongs to the short-lived ‘yuppie in peril’ cycle which includes John Landis’ Into the Night (1985) and Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild (1986), though it pointedly does not share this cycle’s usual emphasis on the hero’s redemption. And Scorsese directly quotes Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939), whose protagonist is also desperately trying to return home, and Orson Welles’ The Trial (1962), which is also structured around a series of encounters between an insecure male and women whose independence he finds disconcerting. But it is the connections Wake in Fright and After Hours have with each other that will surely provide the most fertile soil for those attempting to untangle their mysteries. How ironic that texts which take such a pessimistic view of communal relations should seem so much richer when considered together than they do in isolation.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.