Much of the commentary on A Touch of Sin has focused, quite understandably, on the seemingly dramatic shift it signals in Jia Zhangke’s cinema, the undertone of social criticism coursing through the meditative elegies of Platform (2000), Still Life (2006) and I Wish I Knew (2010) here rendered as a strikingly overtonal symphony of anger and disgust. Undoubtedly, Sin is unique in Jia’s body of work in that it is organised thematically, narratively and formally around acts of violence; but ultimately it is the continuities rather than the ruptures with his previous work that are the most crucial.

People’s Republic of China/Japan 2013

Certificate 15 129m 45s

Writer-director Jia Zhang-ke

Cast

Dahai Jiang Wu

Zhou San Wang Baoqiang

Xiao Wu Zhao Tao

Xiao Hui Luo Lanshan

teenager sending money home Zhang Jiayi

prostitute Li Meng

In Colour

[2.35:1]

Subtitles

Chinese theatrical title Tian Zhu Ding

UK distributor Arrow Film Distributors Ltd

UK release date 16 May 2014

► Trailer

On a formal level, then, A Touch of Sin is a more pronounced iteration of Jia’s overarching aesthetic project. In Platform, Jia built on the lessons bequeathed by Hou Hsiao-hsien by demonstrating how one could turn the ontological promise of the Hou-style long take – uninterrupted duration as guarantee of a sovereign reality – into a heightened formalist endeavour; in all his films since then, he has explored the many ways in which documentary reality and sometimes blatant artifice can fuse, and how the latter can contribute to or help illuminate the former.

And just as Platform used an itinerant group of performers as a bellwether of the transition to a post-Communist China, Jia has kept theatricality front and centre throughout his subsequent films, from the elaborately costumed theme-park performers in The World (2004), to the transparent use of well-known actors amid the parade of real-life subjects in 24 City (2008), to the traditional theatre troupe whose closing, direct-to-camera address puts an appropriately explicit period to A Touch of Sin’s blunt, wholly unambiguous broadside.

To begin with the ruptures, in Sin Jia is most certainly tapping into the current and ongoing genre-fication of art/festival cinema (cf. the maladroit collected works of Park Chan-wook and Nicolas Winding Refn, Brillante Mendoza’s Sapi, Claire Denis’s Bastards, Olivier Assayas’s Boarding Gate etc). Robert Koehler in Cinema Scope has perceptively pointed out the sardonic, almost self-mocking way in which Jia introduces his genre-movie tropes in the film’s opening sequence, not only fetishising the implacable spaghetti-western cool of Wang Baoqiang’s motorbiking bandit and Jiang Wu’s duster-sporting rebel-with-a-cause but quite literally beginning with a bang, as a fireball announces the title (with its winkingly obvious reference to King Hu’s wuxia masterpiece A Touch of Zen).

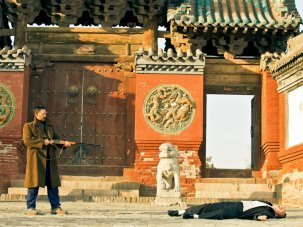

Zhao Tao as Xiao Wu

Having thus frontloaded his generic touchstones, however, Jia spends much of the rest of the film undercutting them even as he quite brilliantly deploys them. Where the enclosed cinephilic universe of a Tarantino shuts itself off from the world while ludicrously claiming to comment on it, Jia’s no less artificial (im)morality play – in which four protagonists react with violence to their variously oppressed situations – sets itself down squarely within a doggedly depressing reality.

Tarantino’s boringly baroque sequences of carnage occur because they ‘have’ to; fetishising genre rather than putting it to some truly conscious end, he invests violence with a meaning unto itself. In Sin, the fatalistic progression towards each differently preordained act of killing – and the determined placement of these actions within a vividly sketched social-political-cultural milieu – saps them of thrill, even as each is rendered with sometimes striking stylistic bravado (particularly the unforgettable sequence where Zhao Tao’s abused bathhouse attendant is suddenly transfigured into a ferocious wuxia warrior).

Tarantino and his fawning critics aggrandise comic-book style and comic-book-style morality into an impoverished, hypocritical conception of ‘art’; Jia artfully uses moments of comic-book amplification to heighten real-world ills, real-world injustices and the sometimes explosive but finally impotent rage of people trapped within a real world made distorted and grotesque by the predations of the powerful.

It’s that quality of directness, of purpose – here particularly fierce purpose – that gives Jia’s plays with fiction and nonfiction both their vigour and their political perceptiveness and bite. The spectacularised, individual violence of Jia’s ‘sinners’ is symptom of and reaction to the quieter but far more massive violence of the state-capitalist behemoth that has made the insanely unreal and unjust reality within which the protagonists exist.

With power comes an increased range of imagination, or rather an increased ability to realise one’s imaginings. What else (apart from a tragedy) is the wholesale uprooting of populations and the erasure of communities effected by the Three Gorges Dam (as portrayed by Jia in Still Life) but the erection of a monumental imagined reality upon the ruins of innumerable smaller-scale realities? What else (apart from repulsive) is the theme-park brothel in the concluding panel of A Touch of Sin’s quadriptych than an exploitative version of The World’s globe-spanning simulacrum, the predatory privileges of wealth adding carnal pleasure to vicarious tourism?

If Jia elicits some cathartic satisfaction by transmuting real-life crimes into florid cinematic revenge fantasies, he is quick to show how ultimately useless and fleeting such liberating fantasies are in the face of a far more capacious, powerful and pernicious unreality.

-

Sight & Sound: the June 2014 issue

Miyazaki Hayao takes flight with The Wind Rises, plus Jia Zhangke on A Touch of Sin, Amat Escalante on Heli, David Thomson on the cinema of World...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.