Web exclusive

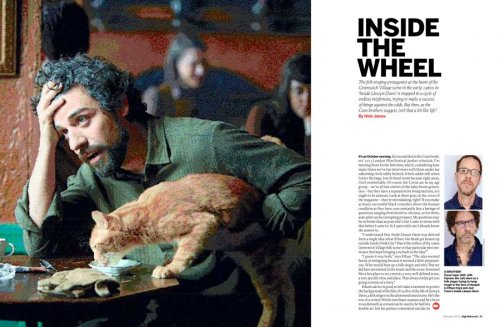

No ambition, no get-up-and-go, no vim: Oscar Isaac as blue troubador Llewyn Davis.

On the grand tour of male failure in the Coen brothers’ universe, Inside Llewyn Davis occupies an unusual place. Blood Simple (1983), Barton Fink (1991), Fargo (1995), The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), The Ladykillers (2004), No Country for Old Men (2007) and Burn After Reading (2008) are populated by men who court disaster by grasping after bags of cash or illusory notions of success. The protagonist of Inside Llewyn Davis arguably has the opposite problem: his lack of interest in worldly achievement is so pronounced that his life is unravelling into chaos.

USA/France/Luxembourg 2012

Certificate 15 104m 34s

Crew

Directors Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Produced by Scott Rudin, Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

Written by Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Director of Photography Bruno Delbonnel

Edited by Roderick Jaynes [i.e. Joel Coen, Ethan Coen]

Production Designer Jess Gonchor

Executive Music Producer T Bone Burnett

Supervising Sound Editor Skip Lievsay

Costumes Designed by Mary Zophres

Cast

Llewyn Davis Oscar Isaac

Jean Berkey Carey Mulligan

Roland Turner John Goodman

Johnny Five Garrett Hedlund

Bud Grossman F. Murray Abraham

Jim Berkey Justin Timberlake

Troy Nelson Stark Sands

Al Cody Adam Driver

Joy Jeanine Serralles

Pappi Corsicato Max Casella

Mitch Gorfein Ethan Phillips

Lillian Gorfein Robin Bartlett

Dolby Digital/Datasat/SDDS

In Colour

[1.85:1]

Distributor Studiocanal Limited

insidellewyndavis.com/intl/uk/

UK release date 24 January 2014

Llewyn (the superbly weary Oscar Isaac) is a singer-songwriter navigating the insecure and unprofitable netherworld between art and commerce in the New York folk scene of the early 1960s. After his musical partner Mike commits suicide, Llewyn scrounges an existence passing the hat in Greenwich Village dives, milking a circuit of friends for ad hoc hospitality and seeking affection from fellow musician Jean (Carey Mulligan, short-changed by a shrewish role that belies the Coens’ usually rich female characterisation).

Llewyn lacks or rejects the slightest entrepreneurial drive: always after a quick buck with no strings, he chooses a day’s wages over royalties on a potential novelty hit and turns down an offer to play second fiddle in a market-oriented trio from a serious producer (F. Murray Abraham in a turtleneck playing Bud Grossman – a nod to the legendary Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan’s one-time manager). “Do you ever think about the future at all?” Jean asks. “The future?” Llewyn replies. “Like flying cars?”

Less mindfully independent than wilfully adrift, Llewyn is a talented but not extraordinary musician who could be in with a shot yet veers between mishap and self-sabotage, spinning his wheels – always crashing on the same couch, as Bowie nearly sang. His awkward squirming between Mammon and the muse brings to mind Barton Fink’s Hollywood career.

Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

But, among the Coens’ films, Inside Llewyn Davis sits most neatly alongside O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000). The films have in common a musical milieu beautifully collated by T Bone Burnett, a hapless hero whose evident shortcomings never quite extinguish our sympathy for him, and explicit references to the Odyssey (here including a runaway cat called Ulysses and a Chicago club called the Gate of Horn, based on a historical venue, in which Llewyn’s dreams diverge from his reality).

But where O Brother’s picaresque was all sepia, bluegrass, hayseed slapstick and family reunion, this film offers a stringent voyage of overcast skies, melancholy folk, soured relationships and no direction home. Llewyn is a character without rudder or anchor; little wonder that his last-ditch attempt to eke out a living in the Merchant Marine never leaves port.

There’s humour here but it’s curdled, somewhat in the vein of A Serious Man (2008), another pessimistic Coen film about the 1960s; the two stories form a bookended counter-history of a decade whose self-satisfied mythologies are increasingly up for revision. Both pictures specialise in dark laughter about subjects that aren’t funny.

Yet while A Serious Man’s Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) is beleaguered by an array of outside forces that invade his life, Llewyn appears bent on engineering traumatic repetitions of his own artistic and emotional low points; he might even be doing himself in. When jazzman Roland Turner (John Goodman, giving a masterclass in obnoxious self-assurance) threatens Llewyn with a curse that will leave him searching for the cause of the pervasive misfortune blighting his life, the gag is that no such hex is necessary.

Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

Was Llewyn always this way, or is he trapped in a spiral of grief after Mike’s loss? This, perhaps, would explain his dolour. Jean could never be this Ulysses’s Penelope, and he will never have an Ithaca. His voyage takes place within a drably Hopper-esque American landscape that sees him boomerang between bad memories and botched opportunities; at the film’s close, Llewyn is missing an early Dylan performance because his drunk mouth has earned him a beating.

Yet there are glimmers of the hearth even here. On the road, Llewyn passes an Ohio city where there lives, he has recently learnt, a child he didn’t know he had. He resists the siren-call of this glowing exit but, on his return to New York, he is heartily welcomed by friends he’s wronged, and he feels their warmth.

Tragedy, the Coens suggest, is not the failure to make money (or art, for that matter) but the failure to feel connected to others. They give us reasons to wonder if their protagonist might not be beyond hope. After seeing his record, also titled Inside Llewyn Davis, Grossman jokes about hearing what’s ‘inside’ him. In response, Llewyn sings a song about a queen who dies in childbirth. But the baby lives.

In the February 2014 issue of Sight & Sound

Inside the wheel

The folk-singing protagonist at the heart of the Greenwich Village scene in the early 1960s in Inside Llewyn Davis is trapped in a cycle of endless misfortune, trying to make a success of things against the odds. But then, as the Coen brothers suggest, isn’t that a bit like life? By Nick James.

Fine tuning

T Bone Burnett, the Coens’ music producer, recalls the challenges of finding songs for Inside Llewyn Davis to breathe life into a fictional folk legend. By Frances Morgan.

-

Sight & Sound: the February 2014 issue

Joel and Ethan Coen on Inside Llewyn Davis, Steve McQueen on 12 Years a Slave, Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, Altman’s The Long...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.