from our January 2014 issue

Her (2013)

Spike Jonze’s new vision of the near future makes its Californians look as if they’re all taking part in an ad for Google or Coca-Cola or a promo for a cover version of ‘We Are the World’.

USA 2013

Certificate 15A 125m 39s

Crew

Director Spike Jonze

Produced by Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, Vincent Landay

Written by Spike Jonze

Director of Photography Hoyte van Hoytema

Edited by Eric Zumbrunnen, Jeff Buchanan

Production Designer K.K. Barrett

Music Arcade Fire

Sound Design Ren Klyce

Costume Designer Casey Storm

Cast

Theodore Twombly Joaquin Phoenix

Amy Amy Adams

Catherine Rooney Mara

blind date Olivia Wilde

Paul Chris Pratt

Charles Matt Letscher

Isabella Portia Doubleday

voice of Samantha Scarlett Johansson

In Colour

[1.85:1]

Distributor Entertainment Film Distributors Ltd

UK release date 14 February 2014

herthemovie.com

► Trailer

This is not a criticism – and certainly not a hint about where and how Jonze earned his directorial chops. Rather it’s a commendation that this film’s dystopia has a plausibly fluffy emotion-stroking feel to it, which is of a piece with contemporary striving to have it all while looking like you’re not trying too hard. Everyone in this film is frighteningly well groomed and dressed smart-casual in pastel-toned, comforting loose clothes that have just a hint of children’s wear about them.

Not least in that vogue is our initially sad protagonist Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), a man whose present irony is that he writes sensitive, tonally perfect letters of affection on behalf of his employers’ clients (the company is like a florist without flowers) while suffering the throes of a break-up from his beloved wife Catherine (Rooney Mara), who has filed for divorce. (One wonders if he’s named after the late painter Cy Twombly, since the tones of pale yellow, magnolia and peach he favours also feature in some of the artist’s paintings.)

Finding it hard to hide his melancholy even from the feisty 3D game avatars he toys with, Theodore thinks about computer dating and, encouraged by his old friend Amy (Amy Adams) and her partner, he hooks up with a woman they help him to choose. Into a single date he and she cram the whole cycle of meet, drink, get friendly, flirt, cop off, argue and break up. When Theodore won’t commit to seriousness, his date switches on a dime from enthusiasm to vitriol: “You’re a very creepy person,” she tells him. This I take to be one of the key ideas of the film, that the instant intimacy of social media is turning us all into creeps.

Theodore, as Phoenix plays him, does not, however, seem like a creep. He’s more the sensitive metrosexual that many advertisers would like more men to be. When he hears about a new operating system that offers an intuitive virtual companion, he buys one and dons the earpiece and dot camera that will change his life.

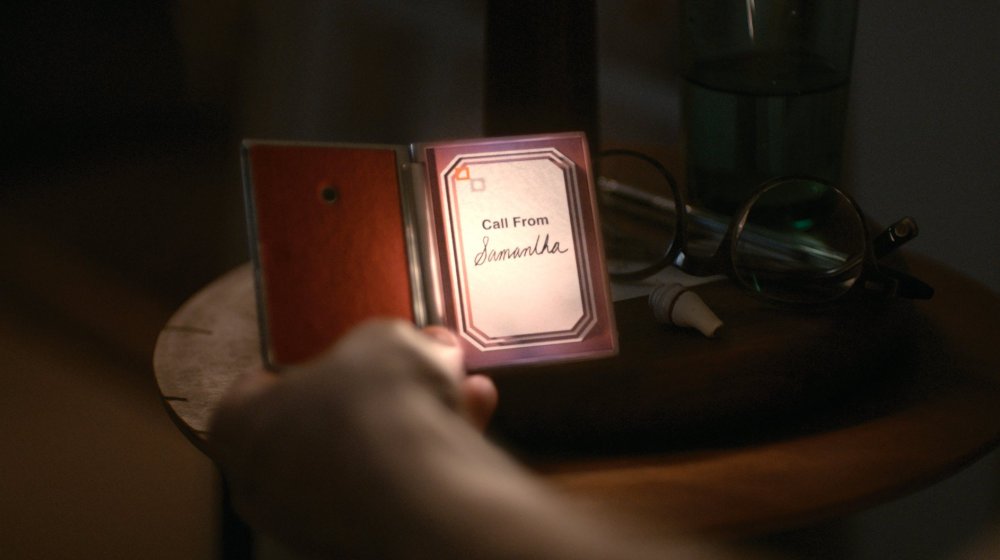

His OS is called Samantha and has the voice of Scarlett Johansson. Immediately curious about every aspect of Theodore’s routine life, she craves intimacy as much as he does. This part of the film feels breathtakingly authentic. It really nails how different personal messaging through the internet is from any other form of human discourse. ‘Samantha’ does not come on as an artificial intelligence but as a breathily fascinating and fascinated fantasy partner-in-life. (When you hear her, you may want one too.)

Theodore is soon enraptured by her, and she seems to want to gorge on real human experience. But virtual sex isn’t enough for her, so she finds a sympathetic woman to act as her physical avatar, although this creeps Theodore out and so he withdraws from Samantha for a while, but not for long.

Her (2013)

In other words, Her is an unapologetic modern love story, except that one half of the couple remains invisible and is not ‘real’. In that sense you could relate it to certain classic Hollywood comedy ideas: James Stewart’s invisible rabbit friend in Harvey (1950), or Lily Tomlin co-habiting Steve Martin’s brain in All of Me (1984), or the voice of Emma Thompson’s ‘life narrator’ in the head of Will Ferrell in Stranger than Fiction (2006), or even, at a small stretch, John Cusack’s experience in Jonze’s own Being John Malkovich (1999). Yet Her is not often comedic in this way – though it has fun with the idea of taking your OS out with another couple and them having precisely the conversations with her they would have had with a ‘real’ partner.

Instead, the film takes its romance as seriously as it does its insights into the way we use electronic media and what it’s doing to us. Jonze and his actors go all out to make the relationship seem real. There’s nothing like the built-in noir damnation between humans and replicants of, say, Blade Runner (1982). The body-brain divide in particular is a clear Jonze theme. His heart-meltingly cute short film I’m Here (2010; homepage), for instance, relates how an automaton librarian meets a risk-taking female automaton so prone to breaking bits of herself that he donates all his body parts to her except for his head, which ends up cradled in her lap.

However, neither I’m Here nor even Being John Malkovich has quite the sophistication Jonze shows in this, his first sole feature screenplay credit. Her is as talky and complex as any film scripted by his erstwhile partner Charlie Kaufman.

Her (2013)

Visually Jonze keeps us marvelling at mood more than style, choosing to keep Theodore’s surroundings mostly fuzzy and distanced. Though the malls and workspaces he travels through reminded me a little of the scenes in 2002’s Minority Report where Tom Cruise and Samantha Morton flee their pursuers while being greeted by advertisements, in Her these environments are anything but aggressive. Others have seen close thematic links with Spielberg’s A.I. (2001).

Thinking about Morton’s ‘precog’ role in Minority Report may be pertinent here. One thing we know about the creation of ‘Samantha’ is that on the set of Her the role was performed by Morton from behind some kind of barrier separating her from Phoenix. Somewhere in the process of postproduction her voice was replaced by Johansson’s.

For me this switch only compounds the film’s displacement between the real and the virtual. Johansson’s voice performance is superb (though it would be great, too, if in the future we could see a Morton-inclusive cut of the film – some chance). Phoenix meanwhile, gives off a transcendent, emerging-from-his-shell joy that’s touching and infectious.

Though I am not of the generation that has come to use the internet for dating purposes, my guess is that those who have and do will find a lot that’s accurate and scary about this projection of our possible collective future. The first thing that hits you is just how irresistible an OS such as ‘Samantha’ would be.

Behind that is a film that’s really sharp about how lonely so many people are, and how modern communications only seem to exacerbate or paper over such problems. That may seem an obvious thing to indicate, but the combination of Jonze’s dialogue, the intensity of the performances and the way the film’s style wraps you up in Theodore and Samantha’s inner-ear relationship makes this feel like a uniquely apt diagnosis of contemporary ills.

In the January 2014 issue of Sight & Sound

Cover story: Computer love

Her, the story of the love between a man and a computer, feels like Spike Jonze’s most personal film yet. But, the director says, from features to pop videos, it’s all personal. He talks about alienation and romance in the age of smartphones and Jamba Juice. By James Bell.

-

Sight & Sound: the January 2014 issue

In our January issue: The best films of the year, plus Spike Jonze’s computer romance, Bong Joonho versus Harvey Weinstein and Alexander...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.