In a long narrated prologue, Pacific Rim gives a precis of what might have been an entire series of films, in which coastal cities around the Pacific are attacked by huge monster specimens, or ‘Kaiju’. The planet’s defence forces prove valiantly unable to cope – leading to the creation of giant, humanoid-shaped fighting machines.

This might be fresh to Western audiences, though Stuart Gordon’s Robot Jox (1990) also featured piloted anthropomorphic combatants (not strictly robots but ‘mechas’), and the Iron Man movies have familiarised multiplexes with the notion of an armoured battle suit. However, Japan has been spinning variations on this premise for decades, whether in live-action movies pitting famous monsters against mecha-doppelgangers (1967’s King Kong Escapes, 1974’s Godzilla vs MechaGodzilla), in which at least initially the flesh-and-blood monsters were the goodies and the metal imitations controlled by wicked aliens or earthly villains, or in anime series like Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995-96).

There’s no denying that Pacific Rim delivers the awesome. Guillermo del Toro is a far better filmmaker than others who have essayed large-scale 3D devastation, such as Michael Bay in the Transformers films and Zack Snyder in Sucker Punch and Man of Steel. Del Toro is known for straddling Spanish-language arthouse fantasy cinema (The Devil’s Backbone, Pan’s Labyrinth) and off-Hollywood edgy comics material (the Hellboy films, Blade II), as well as for his attachment to more unmade, cult-friendly projects than any other filmmaker of his generation (he comes to this after the collapse of his big-budget H.P. Lovecraft dream project At the Mountains of Madness).

A director of taste and sensitivity, he is also a giant super-fan – when a particular Pacific Rim ‘knifehead’ Kaiju looks like a biologically credible redesign of Guiron, the monster that fought heroic flying turtle Gamera in Daiei Studios’ rival to Toho’s Godzilla series, you can be sure it’s a deliberate homage. Anyone who’s ever loved daffy pictures like Gamera tai daiakuju Giron (Attack of the Monsters, 1969) – in which stuntmen in baggy monster suits sumo-wrestle in the middle of miniature cities – and wanted to see a photorealistic version of their set pieces will be stirred by the way that del Toro realises Kaiju (strictly, daikaijû – giant monster) battles here. Corrosive glowing blue monster spittle eats away the head-carapace of a mecha or the side of a skyscraper; a flashback to one character’s encounter with a monster in the ruins of Tokyo gives a child’s perspective on the typical Godzilla rampage in a manner that trounces Roland Emmerich’s pompous 1998 Godzilla reboot; and we follow the devastating effect of a single blow which ploughs through an office block wrecking all in its path until its last spent force sets off a desktop Edison’s cradle.

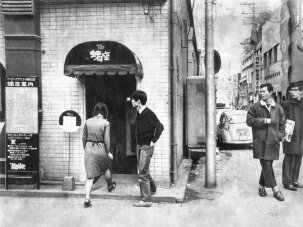

Signs of life: Ron Perlman

In action, the film is breathtaking, but as a whole it suffers from a relative lack of ambition. The invaders’ motivation – and much else, including an inspirational speech delivered by a rasping Idris Elba (“Today we are cancelling the apocalypse!”) – is tipped in from Independence Day (1996), and the human characters are either cardboard jocks or irritating science nerds.

The only human life in the film comes from del Toro regular Ron Perlman as a black marketeer who sells Kaiju body parts for high prices (powdered monster bones are thought to be an aphrodisiac). Eccentric, bizarre but not annoying – unlike the weird boffins played by Charlie Day and Burn Gorman – Perlman’s character is also the only real suggestion that the appearance of giant monsters has changed the world in any way (contrast this with the awe and terror of The Mist or Monsters).

Of all the people we could be spending time with during this crisis, did it have to be a selection of Top Gun knock-off macho militarists with barely a character trait apiece? Buried deep in the script is the notion that the fighting robots – ‘Jaegers’ – need to be piloted by two compatible operators who mind-meld – a concept which ought to lead to compelling drama but is badly mishandled, building into the very premise of the film a requirement for the lead characters to be so dull that their brain hemispheres can mesh without causing nosebleeds.

Independence Day at least showed a range of stereotypes affected by the alien invasion – and it seems odd that del Toro, so sensitive to the plight of innocents caught between the supernatural and brutal soldiery in his Spanish Civil War-set films, should deliver something so gung-ho and militaristic. In an era of drone attacks, the notion of giant piloted robots might even be suspect and fascist – at the dawn of the mecha era, the first instinct of the Japanese was to cheer Godzilla against MechaGodzilla – but this is a hymn to military showboating that ridicules civilian solutions (building a wall around the sea) and can only conceive of punching or blowing things up as a means of dealing with incursions from another dimension.

-

Sight & Sound: the September 2013 issue

In this issue: Television special – the hidden gems of the small screen: when film directors make TV, plus Steve Coogan and Armando Ianucci on Alan...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.