from our November 2014 issue

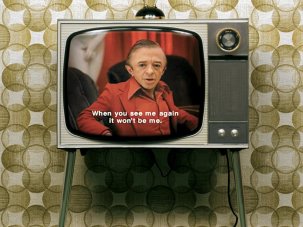

The Knick (2014)

Television might be a writer’s medium, but the idiosyncratic (and allegedly “done with Hollywood”) Steven Soderbergh pushes his own agenda in The Knick, a very distinctive medical drama. It’s the turn of the 20th century at the Knickerbocker Hospital in New York’s Lower East Side, where Dr John W. Thackery (a terse Clive Owen) lives in an age of technological advances but struggles to keep patients alive. The real tension, however, is between the show’s writers (creators Jack Amiel and Michael Begler along with Steven Katz) and Soderbergh, who follows in the footsteps of Cary Fukunaga on True Detective by acting as director for the whole of the show’s ten-episode run; in addition, he serves as cinematographer (alias: Peter Andrews) and editor (alias: Mary Ann Bernard). While the writers have crafted a familiar tale of double lives and moral compromises, Soderbergh’s visual craft skips to its own unique beat. Television has never looked so smart.

The stakes are high – just how high is clear from early in the first episode, when Thackery and his mentor Dr Christiansen (Matt Frewer) are shown attempting a radical new C-section procedure. The tick of a clock sets the tempo for an increasingly erratic operation, with close-ups of gallons of blood gushing on to the pure white floor. The surgery is a disaster – both mother and child dead – and Christiansen puts a bullet in his head, leaving Thackery to lead the floundering institution. Throughout the series, new technologies butt up against crass practices; X-rays and plastic surgery run up against poor hygiene and unreliable electricity sources.

While Thackery’s battles against death make for a fascinating examination of the perils of progress, the rest of The Knick has the familiar concerns of great television: class and gender issues and dark pasts (Mad Men’s bread and butter). Black doctor Algernon Edwards (André Holland) is rejected by the white staff; Cornelia Robertson (Juliet Rylance), a philanthropist’s daughter struggling to turn the Knick into a social welfare beacon, finds her efforts undermined by hospital manager Herman Barrow (Jeremy Bobb), who takes every illegal side deal he can muster to keep the water running and his whorehouse bill paid. Tryingly witty dialogue (“This is madness, yet there is method in it”; “It always looks like rain if you only look at the clouds”) and forced exposition blunt the characterisations.

The Knick (2014)

And yet The Knick remains head and shoulders above television’s recent outpourings. While Amiel and Begler have structured a routine drama, Soderbergh can’t help wedging his personality into it. The opening frames declare his authority: a shallow-focused POV shot of Thackery’s feet in white Balmorals lying crossed in an orange-hued opium den. Then Cliff Martinez’s anachronistic synthesiser score kicks in, as the doctor self-injects cocaine in the back of a carriage, every detail of the procedure captured through a series of rapidly edited close-ups.

As in Haywire and Side Effects, Soderbergh mixes an oversaturated colour palette with a cool emotional tone (one reason the soapy dialogue feels so blunt). The Knick is fuelled by an economic understanding of shots as narrative data, so that every composition and edit feels methodical and essential. In a mid-season episode, unruly ambulance driver Tom Cleary and nun with a dark side Sister Harriet sit down at a local bar. As they finally come eye to eye, Soderbergh shoots their conversation as Ozu-like portraiture. Later, Thackery presents a new surgery technique to a colleague after two straight days of research (plus prostitutes and cocaine); the camera circles around them in a manic handheld long take, matching the doctor’s own delirious state.

Soderbergh’s style isn’t just a grab-bag of showy devices – his craft adds dimensions to the characters that are absent from the writing. In the pilot, Soderbergh transitions between conversations by gliding his camera in an Altmanesque tracking shot, heightening the sense of the hospital as a community. His most ambitious gambit comes at the end of the third episode: for a back-alley brawl with a drunk Edwards, he achieves a thrilling “you-are-there” feeling by attaching a camera rig close to the actor. The muted sounds bring us into the character’s internal reverberations.

While his HBO miniseries K Street took faux-documentary tropes to Washington politics, The Knick feels like Soderbergh’s first truly crafted television work, bringing the disciplined style of The Girlfriend Experience and Contagion to the small screen. Perhaps Soderbergh’s inventive directorial choices wouldn’t stand out so strongly if the writing matched his ambitions. But while “TV is the new cinema” declarations have been easily dismissed by those who prefer their moving images to have visual wit, The Knick finally gives that proposition some legitimacy.

-

Sight & Sound: the November 2014 issue

Mike Leigh gets Romantic, Darwinian sci-fi and the birth of the Method. Plus Nightcrawler, ’71, Gone Girl, The Knick, Venice and Toronto, agnès b,...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.