“Nobody knows anything.” William Goldman’s Hollywood truism, the most quoted sentence in his memoir Adventures in the Screen Trade, has become something of an adage since the book was published in 1983. Even if it is true, it didn’t discourage readers and aspiring film writers from gleaning insights from Adventures into the mysterious, alchemical machinations of the movie biz: at least Goldman knew what he didn’t know. Trenchant and sassy, the memoir remains a fixture on many a film fan’s bookshelf.

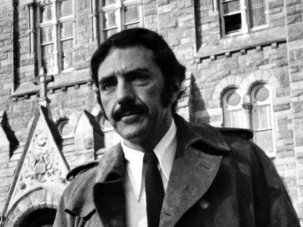

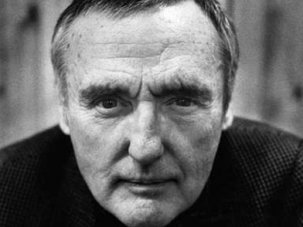

You wouldn’t think it from the movies he wrote, which eschew introspection for action and undercut solemnity with a winking wit, but Goldman came from a deeply troubled home. His father was an alcoholic and took his own life before Bill graduated from high school in the late 1940s. Like his older brother James (The Lion in Winter, 1968; Robin and Marian, 1976) he became a novelist, playwright and screenwriter, in ascending order of fame and influence.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

His third produced (and first original) screenplay, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, was a snappy cowboy caper starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman. Goldman identified the script’s weaknesses in his book: a surfeit of smart-ass dialogue, too many reversals, overweening “cuteness” – but the movie was a smash in 1969, won Goldman his first Academy Award, and arguably defined the counter-cultural moment more accurately than critical totems such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Easy Rider (1969) and The Wild Bunch (1969). It made Redford a star, and Goldman became one of his go-to writers on vehicles such as The Hot Rock (1972), The Great Waldo Pepper (1975) and All the President’s Men (Goldman’s second Oscar, though he described the innumerable rewrites on the film as torture; Redford added insult to injury by minimising Goldman’s contribution to the finished film.)

The 1970s were his peak years, with seven produced screenplays to his name, including Marathon Man (1976) and Magic (1978), both from his own novels. But his most beloved film must be The Princess Bride (1987), again based on his novel, though it’s a conceit of the book that Goldman disavowed authorship by claiming the work was an abridgement of an older tale. A fairytale for cynical seen-it-all-before kids, this is the most Goldmanesque of movies, romantic without being yucky, classical but quirky, tricky but this time not too tic-cy, tapping into a childlike yearning for heroism and adventure. He has one more notable credit, the claustrophobic Stephen King adaptation Misery (with The Princess Bride director Rob Reiner), along with several potboilers and the usual motley medley of ghost drafts and revisions.

In the January/February 2019 issue of Sight & Sound

Act natural

Over more than half a century, Robert Redford has effortlessly blended traditionalism, predictability and inscrutability in a host of charismatic performances. By Christina Newland.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.