A byword for brilliant acting and classy French sexiness, Jeanne Moreau is forever associated with the great European art films of the 1960s, her career marked by, among others, her roles in François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962), Michelangelo Antonioni’s La notte (1961) and Luis Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid (Le Journal d’une femme de chambre, 1964). And yet, this actress who became the embodiment of the new post-war cinema was classically trained for the stage, and this epitome of French womanhood was half-British.

Jeanne Moreau’s mother was an English dancer (a Tiller Girl), her father a Parisian restaurateur. She was born in Paris on 23 January 1928. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she tried ballet, but the stage was her vocation, revealed to her when she saw a performance of Anouilh’s Antigone in March 1944. She joined the Comédie Française in January 1948 and was a student there until 1951; she also attended the Conservatoire. In 1949 she married Jean-Louis Richard and they had one son, Jérôme, born the same year, but the couple separate in 1951.

While her mother approved of her career, her father frowned on the stage and she recounted that he slapped her on learning she was performing in a play. Undeterred, the actress whom Louis Malle would later term “the Sarah Bernhardt of her generation” began building up a stage career, appearing among others at the Théâtre National Populaire, where she starred opposite Gérard Philipe. This background gave her considerable talent a solid professional foundation, the ability to range across the whole spectrum of parts, and the seal of high culture. A watershed as far as she was concerned was appearing in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1956, directed by Peter Brook. The cinema, however, had already beckoned.

Touchez pas au grisbi (1954)

In the early 1950s Moreau rapidly became a rising starlet of French mainstream cinema, specialising in spirited, sexy young women. As such she appeared in comedies (Pigalle-Saint-Germain des prés, 1950), literary adaptations (La Reine Margot, 1954), dramas (The Doctors/Les Hommes en blanc, 1955) and thrillers such as Honour Among Thieves (Touchez pas au grisbi, 1954). In the latter, as a drug-sniffing gangster’s moll, she is the recipient of another notable slap, this time conferred onscreen by the film’s star, Jean Gabin. With the success of La Reine Margot and Honour Among Thieves, among other films, she could easily have carried on in this vein – but her own cultural leanings went in another, less mainstream, direction.

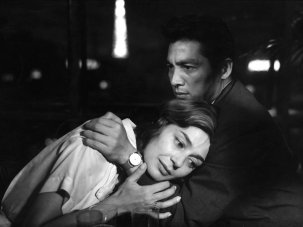

Moreau’s relationship with the director Louis Malle and the two films they made in the late 1950s would alter the course of her career – and arguably that of post-war French cinema. If Malle’s thriller Lift to the Scaffold (Ascenseur pour l’échafaud, 1958) is recognised as a precursor of the French New Wave, it is partly for its groundbreaking location shooting; but just as important is its moulding of the Moreau character as a new type of sensual heroine, a modern femme fatale without the clichéd trappings of the traditional vamp. Malle famously broke the rules of conventional star presentation by removing most of her make-up. As he said, “cameramen would have forced her to wear a lot of make-up and they would put a lot of light on her because, supposedly, her face was not photogenic… They were horrified. But when Ascenseur pour l’échafaud was released, suddenly something of Jeanne Moreau’s essential qualities came out.”

Moreau’s atypical beauty, what she called “the rings under my eyes and my asymmetrical face”, fitted the young filmmaker’s desire for a more authentic cinema and at the same time a more cerebral type of female eroticism, based on the face rather than the body. Opening his film with a huge close-up of Moreau’s face, he then proceeded to film her moodily walking the night-time streets of Paris in the rain, to an evocative soundtrack by Miles Davis (she is looking for her lover who has, at her instigation, killed her husband).

Their next film, The Lovers (Les Amants, 1959), caused an even bigger stir with her ‘scandalous’ representation of female desire (she plays a woman who leaves her husband and daughter for a younger lover). Lift to the Scaffold and The Lovers were a turning point, symbolically erasing her earlier professional background, her previous public image and even her looks. She was ‘reborn’ as a New Wave star.

Diary of a Chambermaid (1964)

There followed an intensely productive decade for Moreau in which she became the supreme incarnation of cultured and sensual femininity, tinged with danger or perversity (an echo of her earlier insolent minx). The perversity was well in evidence in Roger Vadim’s Dangerous Liaisons (Les Liaisons dangereuses, 1959) in which Moreau excelled as the scheming Juliette de Merteuil, as she did as the title heroines of Joseph Losey’s Eva (1962) and Luis Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid. Moreau’s versatility made it possible for her to portray the myriad nuances of this new femininity: passionate love (Peter Brook’s Seven Days… Seven Nights, aka Moderato Cantabile (1960), which won her a best actress prize at Cannes), ennui (La notte), seduction (Jules et Jim), eccentricity (Orson Welles’ The Trial, 1962), vulnerability (Jacques Demy’s 1963 La Baie des anges, in which she wears startling platinum blonde hair), or the lethal determination of the wronged woman (The Bride Wore Black, 1968). She was a spy in Jean-Louis Richard’s Mata Hari, Agent H-21 (1964) and a revolutionary in Louis Malle’s Viva Maria! (1965). In this last film, co-starring Brigitte Bardot, she showed that she could also handle comedy.

La Baie des Anges (1962)

The 1960s for Moreau were also marked by her friendship and collaboration with Orson Welles, appearing in four films he directed: The Trial, Chimes at Midnight (1965), The Immortal Story (1968) and The Deep (1970). He rewarded her by calling her “the greatest actress in the world”.

This stunning run of films – and there were others – showcased her consummate yet invisible performance style and willingness to adapt to the universe of a range of filmmakers. In 2008 Moreau told Cahiers du cinéma, “I have no special technique. Maybe a few habits, but each time I like to modify them, depending on the director.” But across a huge range of films, her dark-haired elegance, her sensual, downturned mouth – often compared to Bette Davis – and her smoker’s voice (in the days when this was considered sexy rather than incorrect) projected a unique blend of intelligence and sensuality.

The most enduring example of this persona is probably her incarnation of Catherine, the heroine of Jules et Jim. This film shows off her character’s duality as both luminous, life-affirming presence (see for instance her beautiful rendition of the film’s song, Le tourbillon de la vie) and self-destructive femme fatale (lethal to men and to herself). Visually, these two aspects were encapsulated in the way her dazzling smile suddenly illuminated her downcast pout.

The Old Lady Who Walked in the Sea (1991)

Inevitably, after such cinematic heights, Moreau’s 1970s films felt somewhat disappointing. This may well have had something to do with the films themselves, but at the same time her age (she turned 40 in 1968) meant that she shifted slowly to mature ‘older’ roles. She married the director William Friedkin in 1977 but they divorced in 1980. She kept working, making more than 20 films in that decade, but she tended to appear either in relatively minor productions or in restricted roles in more prominent films. Her characters retained a sexual dimension, albeit a frequently ‘tragic’ one. For instance, in Bertrand Blier’s Going Places (Les Valseuse, 1974), her criminal emerging from jail is picked up by two petty crooks (Gérard Depardieu and Patrick Dewaere). After passionate sex with both of them, she violently kills herself.

Subsequently, she was often cast as a woman ‘growing old disgracefully’, in a varied and still abundant number of films – notably R.W. Fassbinder’s Querelle (1982), in which she embodies the camp, overdressed, madame of a brothel, and Laurent Heynemann’s comedy The Old Lady Who Walked in the Sea (La Vieille qui marchait dans la mer, 1991), for which she won a best actress César. In Luc Besson’s Nikita (1990) her brief but striking scenes show her as a kind of godmother to the young heroine killer Nikita (Anne Parillaud), teaching the latter that there are only two important things in life: “Femininity and the ways to abuse it”.

The Bride Wore Black (1968)

Since the late 1990s, Moreau’s international career has been uneven, with high-profile though disappointing films such as Ismael Merchant’s The Proprietor (1996), in which critics agreed she was by far the best thing – a recurring assessment. In France, however, she experienced something of an upturn as a grande dame of the French screen, thanks to big-budget television productions directed by Josée Dayan such as the biopic Balzac (1999) and historical dramas such as Les Misérables (2000) and Les Rois maudits (2005), all of which brought her talent and her aura to a much wider audience than in her heyday.

This had been a period of renewed recognition and lifetime awards, including, among a plethora of prizes at virtually all the world’s film festivals, a career Golden Lion at Venice in 1992, an honorary Oscar in 1998, two honorary Césars (in 1995 and 2008) and an honorary Golden Palm at Cannes in 2003. She was President of the Césars ceremony in 1978 and headed the Cannes festival jury in both 1975 and 1995, a unique honour. In 1998 the American Academy of Motion Pictures awarded her a lifetime tribute and in 2001 she was the first woman to be elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in France.

Les Amants (1958)

While Moreau’s reputation undoubtedly rests on her work as a star of more than 140 films made between 1949 and 2015, her activities were not confined to acting: she showed commitment to the cinema in many other ways. Joining the substantial ranks of French actresses-turned-filmmakers, she made two respected fiction films as director: Lumière (1975) and L’Adolescente (1978). In the former, she reflects on the world of film as it affects actresses through a portrait of four women, one of whom she plays. She also directed a documentary on Lillian Gish (1984) and a music video for singer Khadja Nin (1998).

An indefatigable supporter of auteur cinema, she headed the influential Commission d’avances sur recettes which allocates funds to auteur films and helped struggling young filmmakers; in the late 1990s, through Equinoxe, she also supported budding scriptwriters. Later she ran a film school in Angers in the west of France (Les Ateliers d’Angers). Finally, partly as a result of her cult performance of Le tourbillon de la vie in Jules et Jim, she acquired a reputation as a singer, and altogether recorded six albums.

Most of all, though, she put her highly recognisable voice to the service of film, recording an impressive number of voiceovers as well as imprinting its signature on so many of her memorable performances. Reflecting on her role in Lift to the Scaffold in the trade paper Le Film français, former French minister of culture Jack Lang told Moreau: “The short telephone scene has remained imprinted on my memory: the images, of course, but especially your voice, which resonates.”

Jules et Jim (1962)

While there is absolute consensus on her talent and professionalism, Jeanne Moreau offers an interesting paradox when it comes to her screen iconography, projecting figures of both modernity and an unchanging ‘eternal feminine’. Many of the roles for which she remained most famous (the heroines of Eva, Jules et Jim, The Bride Wore Black) were conceived as dangerous, even morbid. Yet her performances, and her off-screen persona as a lucid, erudite and forward-looking woman, transformed these types into a radiant, positive presence – a “brilliant, witty, original” woman, in the words of the director Marcel Ophuls. This is evidently due to her exceptional talent, her energy and affirmative personality, but also because, for her, the cinema was, as she said, “life itself”.

In the December 1998 issue of Sight & Sound

The indiscreet charm of Jeanne Moreau

Sexy but cultured, sensual but cerebral – and with a designer wardrobe – Jeanne Moreau embodies modern woman. But it is her face that matters, argues Ginette Vincendeau.

Access our complete digital archive of every issue of Sight & Sound and the Monthly Film Bulletin since 1932:

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.