Web exclusive

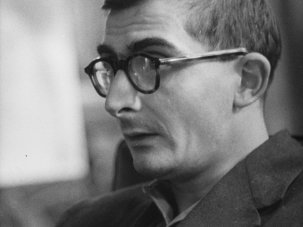

Jean-Luc Godard (left) and François Truffaut

“It’s not a film about the French New Wave, it’s a film about the friendship between Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, and how that ended”, says Emmanuel Laurent of his documentary Two in the Wave, whose British release coincides with a two-month retrospective of Truffaut’s films at the BFI Southbank.

Constructed by Laurent and the writer and narrator Antoine de Baecque out of archival materials – a mixture of film clips, interviews, photographs, and newspaper and magazine cuttings – Two in the Wave traces how these two comrades-in-arms ended up as sworn enemies: neither spoke to one another in the decade before Truffaut died aged 52 from a brain tumour in 1984.

Back in the 1950s Truffaut and Godard were the trailblazing critics of Cahiers du cinéma and Arts magazines, pouring vitriolic attacks on traditional French cinema and praising visionary auteurs such as Hitchcock, Hawks, Ray, Renoir, Bergman and Rossellini. Both made superlative filmmaking debuts – The 400 Blows (Les Quatre cents coups, 1959) and Breathless (A bout de souffle, 1960) respectively – which helped bring the nouvelle vague to international attention. Truffaut even wrote the original treatment for Godard’s Breathless, and helped his colleague finance the feature. During the 1968 protests against the government’s sacking of Cinémathèque Française head Henri Langlois they were charged at by riot police, and they also helped shut down that year’s Cannes festival.

By 1973 however they had irreparably fallen out. In an exchange of venomous letters the now Maoist Godard accused Truffaut of having surrendered his artistic integrity; in a 20-page reply Truffaut denounced his old friend for his selfishness and hypocrisy. To Godard, films had to serve the revolutionary cause; subordinating cinema to political militancy was anathema to the humanist Truffaut.

Two in the Wave originated in Laurent’s desire to collaborate with de Baecque, a former Cahiers du cinéma editor who’d written a biography of Truffaut.

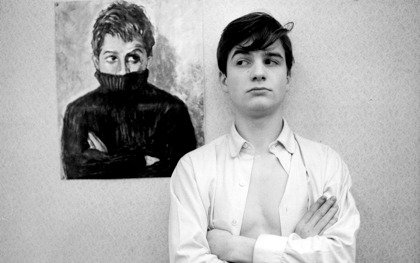

“Neither of us could see the point of making another film about the French New Wave”, Laurent says, “but we thought that the subject of the friendship that ends in divorce was less well known. People don’t realise how close Godard and Truffaut were in terms of how they exchanged ideas and how they were artistically linked. Take Jean-Pierre Léaud. In the role of Antoine Doinel, he was an alter ego for Truffaut across a number of his films. Then Godard played with that image in Masculin, féminin (1966) and La Chinoise (1967). Léaud is an important character in our film; he’s in both the opening and closing sequences. He’s torn between these two fathers.”

Emmanuel Laurent

Indeed, through the juxtaposition of sequences from Truffaut and Godard’s films we can appreciate, per Laurent, “how much they talked to one another through cinema. So after Jules et Jim (1962), Godard shot Une Femme est une femme (1961) with Jeanne Moreau and had Jean-Paul Belmondo ask her how the shooting of Jules et Jim is going. When Truffaut had made La Peau douce (Silken Skin, 1964), a drama about adultery, Godard replied with Une Femme mariée (1964).”

From the outset Laurent and de Baecque were determined to rely almost exclusively on archival footage. They immediately ruled out interviewing the survivors of that era, whether stars (Anna Karina, Léaud, Belmondo) or directors (Jacques Rivette, Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda, Godard himself).

“We wanted to remain as much as possible in the present tense, staying in the period in which the film is set”, says Laurent. “I didn’t want old people talking about their pasts: that would have been sad. For me it’s a film about youth, and how this extraordinary influx of young talent came into the film business. Truffaut was only 27 when he made The 400 Blows; Godard was 29 when he made Breathless.”

Less effective is the way the film uses French actress and director Isild le Besco to act as a silent bridge between present and past. The shots of her studying back copies of Cahiers du cinéma or visiting important cinematic venues in Paris seem superfluous. Laurent readily admits that it’s a device “which doesn’t work as well as I hoped. I wanted to use her because Godard had asked her to be in one of his most recent films. I felt that she could be a representative of today’s generation looking back at events from 50 years ago. It was Truffaut who said that all you need for a film is a woman with a beautiful face.”

Jean-Pierre Léaud in Antoine et Colette (1962)

Two in the Wave strives hard to present a balanced account of the relationship between its subjects. During the editing process, though, Laurent was concerned that the film’s sympathies would seem to lean to Godard.

“People tend to side with the revolutionary, the guy who breaks the system, because that’s more glamorous and romantic. Godard was like a Picasso, somebody who breaks all the rules. That’s why I’m so glad we got the letter where Truffaut praises Matisse. Truffaut didn’t want to revolutionise cinema; he wanted to do it better, to make it more real and sincere.”

There’s another important painting reference in Two in the Wave, when in a clip from Breathless we see Jean Seberg’s Patricia place on a hotel-room wall a poster of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Head of a Young Girl and proclaim to Michel (Jean-Luc Belmondo) her love of the painter. (Also visible are reproductions of Picasso’s The Lovers and Paul Klee’s The Timid Brute.) For Laurent, there are significant connections between the New Wave filmmakers and the Impressionists: in both cases “these artists broke away from a very rigid academy and they chose to paint and film their own time. The way they envisaged art and the way they wanted to be in sync with society was very similar. Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s son Jean, whom Godard and Truffaut worshipped, was an important bridge between these different generations.”

Having immersed himself in their friendship and revisited their films, did Laurent find his own opinions about the two directors changing?

“Not really”, he says. “Personally I’m still more inclined towards Truffaut’s films, especially those like L’Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child, 1969) and L’Argent de poche (Small Change, 1976), because they moved me so much when I first saw them as a young man. Later I learnt to make films through editing, and that’s where Godard opened my mind. So Godard make me think, but Truffaut moved me. Actually my favourite New Wave filmmaker is Jacques Demy, but that’s another story – and, I hope, another film…”