Despite a programme celebrated in advance for its brimming promise, what nearly spoiled Venice’s sudden eminence this year was that two excellent films shown in back-to-back press screenings on the festival’s second morning threw such a mountainous shadow over the rest of the programme that several films that followed felt anti-climactic – until, that is, another double whammy arrived.

The 75th Biennale di Venezia runs 29 August-8 September 2018.

The first pair I’m referring to are Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Favourite and Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, films utterly distinct from one another that have in common only that rare experience of all cinema’s elements working together towards an invisible kind of perfection, plus the fact they foreground female characters in a festival that’s light on women directors.

The Favourite is a deliciously spiteful British costume drama that finds itself in a fashionable niche once occupied by the films of Peter Greenaway. It draws lustily on 18th century morality tales and satires, with their switcheroos of fate, from Voltaire’s Candide to Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress, and marries these to the blackly comic winking misanthropy for which Greek director Lanthimos is best known.

Sex and power shenanigans in the court of Queen Anne bring together an opulent palace-full of two-faced chancers with a sting in their tail (aided by a script sewn with earthy barbed witticisms from Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara). Olivia Coleman is on staggering form as the capricious, seemingly gormless yet at times instinctively insightful Queen; Rachel Weiss gleefully incarnates the strutting, ruthless Lady Marlborough, whose powerful influence over Anne is mystifying until her impoverished cousin, Emma Stone’s Abigail, wins her trust while beginning to snoop on her. It’s a sophisticated romp through the more malignant shades of English eccentricity for which any one of the three female leads could win a major award.

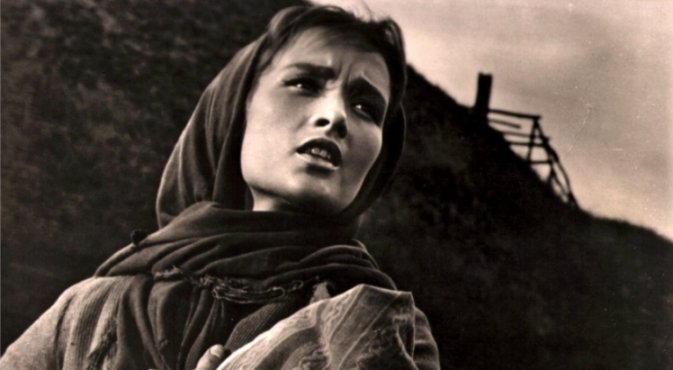

Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma

Roma, by contrast, is a loving semi-autobiographical portrait in monochrome of the Mexico city of the early 1970s, seen through the eyes and mostly silent lips of Cleo (Yalitzo Apar), the Mixteco servant who, in the characteristic Mexican manner, is also regarded – however difficult that concept is to accede to – as part of the family. And this family, consisting of mother Sofia (Marina de Tavira), three boys and a girl of school age, plus Adela (Nancy Garcia), another servant, is about to be abandoned by the beloved but gutless father Antonio (Fernando Gregiada). Cuarón, while rebuilding the vanished city of his childhood, shapes a multi-narrative with Cleo’s unfortunate romance with a martial arts fanatic as the main thread but with family struggles, an earthquake and a massacre of student protestors all helping to create a visual immersion that’s never in your face but prefers to allow the emotion to percolate through the filter of daily circumstance, like the dogshit that litters the reconstructed home’s symbolic garage area. It’s one of the finest films I’ve seen in a long time.

Tim Blake Nelson in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

That shadow fell on several films. Take the Coen brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a lovingly crafted portmanteau paen to old western short stories made initially as episodic television for Netflix but bundled together here as a binge experience of six episodes lasting 133 minutes and spoofed with a macabre eye for how lethally wild the west could be.

The film’s title is also given to the first story up. The character Buster Scruggs is a deadly but pristinely garbed singing cowboy – played with patent aw-shucks ingratiation by Tim Blake Nelson – who makes fun of people in song after he kills them.

Thereafter the tales, though sharp, offer diminishing returns: there’s one about a bank robber thwarted in an unlikely manner, another concerns a limbless English actor/orator whose appeal is declining, Tom Waits plays a gold prospector who arrives in a gorgeous Edenic valley and sets about despoiling it while singing snatches of Mother Magee, and the final and weakest tale is set on a stagecoach full of ‘characters’ whose driver will stop for nothing. We are all so used to what the Coens do that these tales too often seem polished and familiar beyond the point of interest.

Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga in A Star Is Born

What’s most interesting to me about the A Star Is Born remake, conceived by Bradley Cooper and starring himself and Lady Gaga, is how similar, if less cornball, it is in terms of the music to the 1976 version with Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson, especially when you think how much showbiz had changed after the 1954 Judy Garland/James Mason version. Cooper plays Jackson Maine, a passing-his-peak alcoholic rock singer (in a Kings of Leon mould), Gaga plays a version of her pop self and proves she can really act as the ingénue performer destined for the top. Cooper here is out to convince us of the full range of his talents – I buy his charisma and performance but wasn’t convinced by his songs. On the other hand words like chutzpah and razzamatazz naturally associate themselves with Gaga. She puts it all out there and if you love that kind of power singing you’ll love this.

Among other films that suffered in the shade was Olivier Assayas’s lecture-like drama of business and sexual affairs among the denizens of book publishing, Non-Fiction (Double Vies), which juggles over-familiar (to me at least) arguments about how digital is ruining everything and treats some its female characters as mere cyphers.

Rick Alverson’s The Mountain

I liked the look of Rick Alverson’s painstakingly mordant road movie The Mountain, informed as it is by the downbeat end of the 1950s iconography spectrum, all stripped-bare institutional rooms, their autumnal colours leeched towards monochrome, but it has many irritating elements. When the taciturn young protagonist, played by Tye Sheridan (who seems to be channelling some of Barry Keoghan’s playing from The Killing of a Sacred Deer), loses his figure-skating teacher father (Udo Kier) to a heart attack (as one might) he is befriended by travelling neurological electro-shock therapist Jeff Goldblum (as one often is). What follows is a series of edgily grotesque scenes that resemble Roy Andersson’s sketches but lack their humour. What kills the film altogether is Denis Lavant’s performance – not so much scene-stealing as film-eating – as the drunk father of a girl patient the protagonist becomes fascinated by.

The anti-climax was ended when László Nemes’s stunning political costume drama Sunset and Jaques Audiard’s characterful western The Sisters Brothers played.

Jake Gyllenhaal and Riz Ahmed in The Sisters Brothers

The gradual humanising of a pair of vile contract killers, played by Joaquin Phoenix and John C. Reilly, is the theme of The Sisters Brothers. They’re sent by Oregon city’s mob boss, the Commodore (Rutger Hauer), to track down one Hermann Warm (Riz Ahmed), who has a formula that speeds up the process of panhandling for gold, and is going to be befriended and detained by the Commodore’s detective, John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), so that the Brothers can torture him for the formula. What proceeds is very like a classic 70s western, with excellent dialogue and the violence becoming less and less present and relevant as we go along.

The same technique Nemes used in his landmark holocaust depiction Son of Saul – of keeping the camera close on one individual’s face or back of head most of the time and having the mise-en-scène of many crowd scenes take place around the edges of the frame – is used again in his 1913 Budapest-set Sunset, which concerns the fate of the seemingly untouchable Irisz Leitner (Juli Jakab).

Juli Jakab in Sunset (2018)

Irisz tries to get employed as a milliner at Leitner, the famous company that still bears her parents’ surname, a symbol of the belle époque, but is met at first with self-indulgent resistance by the current owner, Oszkár Brill (Vlad Ivanoff). The milliners are picked for their beauty as much as their skill, and once Irisz has inveigled her way back in she learns that her murderous renegade brother Kálmán is connected with one who seems to have disappeared.

Thus Irisz begins in her headstrong fashion to unravel what exactly is going behind the mutual facades of Leitners and the gentlemen-only clubs attended by Kálmán’s seemingly anarchist followers. Despite the odd non-sequitur and seemingly pointless red herring, Sunset is a high intrigue that fascinates to the end, and fully justifies its stunning unforeseen ending.

Joachim Lafosse’s Keep Going (Continuer)

Given the coverage this glittering competition’s big films are getting, with films by Carlos Reygadas, Paul Greengrass and Jennifer Kent still to come, I’d like to mention here a couple of smaller films that quietly impressed.

Joachim Lafosse’s emotionally claustrophobic present-day western Keep Going sees Sybile (Virginie Efira), a formerly neglectful mother, reunite on a dangerous horse-trek across Kirgyzstan with Samuel (Kacey Mottet Klien), the adult son she once abandoned. The son fuses his techno-head fury at the world with a great tenderness towards horses, and the mother keeps up a blasé front that disguises her own fortitude. Samuel may be the somewhat stereotypical angry Francophone youth but the beauty of the landscape and the patience with which Lafosse teases out sensitive performances from both leads renders some superb moments.

David Oelhoffen’s banlieu narcotics drama Close Enemies (Frères ennemis)

Any cop-pursues-criminal-who’s-a-mirror-image tale will very likely nod towards Michael Mann’s Heat and David Oelhoffen’s banlieu narcotics drama Close Enemies is no exception, but the pleasing thing is that it honours Mann’s film so quietly and carefully, allowing the geography of the project estates that rim Paris to dictate much of what happens. Manu (Matthias Schoneharts) is the drug gang insider who was once best friends with narco cop Driss (Reda Kateb), but, after a drug deal with Manu present is hijacked by a shooter on a scooter, Manu is suspected of betrayal. Variety called it “solid but standard issue’ and they’re not wrong but it has more soul that that dismissal allows.

Women Make Film: A New Road Movie through Cinema (2018)

With the exception of all the great women’s performances I’ve mentioned here, the programme has felt otherwise very masculine. The first four hours of Mark Cousins’s 14-hour project Women Make Film establishes the argument for a better gender balance of directors going forward, and it’s pleasing that Venice has now signed the pledge to improve matters. In the meantime, at its halfway point, the festival has settled down to a more even pace at which expectations need not be so difficult to satisfy. There’s no question that its 75th year is already one to remember.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.