Web exclusive

A-list pleasure: Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity

One of the best-applauded most welcome elements of this year’s Venice film festival has been the short archive news footage excerpts from vintage editions of the world’s oldest film festival. These brief Pathe News-like items have a sly commentary of satirical edge, likely to remark on Pasolini’s strange disinterest in the beautiful actresses surrounding him or, in the Fascist era, to praise the ‘health’ of the films shown.

70th Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica la Biennale di Vienezia

28 August-7 September 2013 | Italy

But they also have an unfortunate tendency to induce an impossible (for most of us) nostalgia for Venice’s golden days (1950s-60s), when the open-air theatre on the Lido was carefully looked after to keep it in the best condition, and opening night would take place in Venice proper and the great names of world cinema lined up to compete on what for us is an unimaginably high level of achievement.

Those days seem long gone. This year the city’s infrastructure seems under stress with fewer buses and water buses. The festival itself is still scarred by its long-running redevelopment of the Casino area. It is an expensive place to come and the numbers of attendees this year have reflected that with hardly any screenings full to the brim.

At first the film programme seemed like it might buck this feeling of creeping dilapidation. It began, as it should, with the huge A-list pleasure of Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, in which half the countdown-to-doom fun is deciding which way is up and Sandra Bullock and George Clooney’s only recourse to hope – when the debris hits the tether – is the beauty of the earth they’re orbiting.

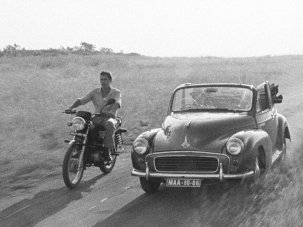

Then, however, we had three days worth of ordinary-to-very-ordinary fare. The shaky performances in Bruce LaBruce’s Gerontophilia dilute the provocative fun of its young male protagonist’s sexual yen for the oldsters he cares for; Rick Osterman’s well-crafted Wolfskinder, about 1946 German children trying not to get shot or raped by Russian soldiers, suffers from resembling too much Cate Shortland’s better-constructed Lore; Australian John Curran’s Tracks, an absorbing recreation of one woman’s epic 1977 trek across the outback with three camels, can’t quite shake off its lack of dramatic incident, though Mia Wasikowska’s performance as trekker Robyn Davidson is outstanding.

I’ll save for the next edition of the magazine more intriguing semi-disappointments such as Edgar Reitz’s 19th century Heimat prequel saga Home for Home – Chronicle of a Vision, Paul Schrader’s attempt to make the skittish Lindsay Lohan come through in The Canyons, Hayao Miyazaki’s paen to aircraft design (and perhaps unintentionally the Japanese imperial project) The Wind Rises and James Franco’s wild inhabiting of a Cormac McCarthy character in Child of God. Instead I’ll concentrate on the three exceptional standouts of the festival so far.

Constant sacrifice: Yoru no henrin (The Shape of Night)

The first is an archive treat: Noburu Nakamura’s Yoru no henrin (The Shape of Night, 1964). It’s a simple enough tale of a young woman who falls for a yakuza underling and gets put on the street at first by him and then, more brutally, by his gang bosses.

What sets it aside as one of the most poignant films about prostitution is its imaginative conception of her world. The camera angles and movements, the colour scheme and editing all work brilliantly to illustrate her constant sacrifice and lead us to emotionally internalise the gaudy city as a dazzling parade that, despite an offer of escape, always leads her back to her situation. Stylistically the film anticipates the Wong Kar-wai of In the Mood for Love and echoes Douglas Sirk at his most stirring.

Kelly Reichardt’s films like to put neurasthenic types into tough situations they’re not properly raised or prepared for. In Night Moves she has three eco-terrorists prepare and carry out a raid on a dam.

Jesse Eisenberg as Josh in Kelly Reichardt’s Night Moves

Like a great macho heist movie (such as Rififi) or many war movies about sabotage, the film is not too concerned (at least at first) with the motivation behind these characters’ actions. Character is action here as loner organic farmhand Josh (Jesse Eisenberg) gets together with idealistic spa-worker Dena (Dakota Fanning) to buy a speedboat and take it to his up-for-anything friend Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard) only to find that they’re short of enough fertiliser for their raid.

The sequence where Dena has to persuade the local dealer to part with 500lb of fertiliser when she doesn’t have sufficient ID gives us a chance to see this superb, restrained and utterly convincing cast working off each other. After that, it’s pure action until the results of the raid are known and the film tips into a different kind of drama, where the consequences of their actions show the trio’s true colours.

Some have said it would have made a purer film if Reichardt stuck to the raid, but for me this last film noir-like segment has a devastating accuracy about the thin line between ordinary behaviour and the unthinking promulgation of terror.

Well-drilled automatons: Greek tragedy Miss Violence

Where Night Moves gives us the pleasure and satisfaction of an established voice having achieved perhaps her finest work yet, Alexandros Avranas’s Miss Violence is so gruelling a drama about a family striving to keep its secrets after a daughter’s suicide that audience pleasure doesn’t come into it. Yes, it’s pretty easy to guess broadly in what area those secrets might be, given that the family behave like well-drilled automatons most of the time. However, Avranas’s handling of the slow reveal and the space of the grandparents’ apartment in which they all live is extraordinary.

So the boon here is the recognition of a film that could not have been better acted and constructed to achieve its grim intensity. You’ll recognise the tone as resembling that of the group of Greek talents that brought us Dogtooth and Attenberg, but it is a more conventional work that harks back as much to Attic tragedy.

There have been few other glimpses of intriguing stuff here (Miguel Gomes’s short Redemption, a good film about Sam Fuller called A Fuller Life), but I’m hoping the next three days will bring more.