from our September 2012 issue

The past is indeed a foreign country in this extraordinary third feature from Portugal’s Miguel Gomes, which traces a unique filmic form to tell a story about vicarious living and bitter experience.

Across two disparate segments we meet a seemingly dotty elderly woman and then see her secret African past played out almost as if it were an old movie, a singular unfolding that registers the psychological ripple effect of Portugal’s colonial legacy while also conjuring a gauzy sense of Hollywood’s far-off days of pith-helmeted adventure. The juxtapositions ping across emotional, historical and celluloid landscapes, yet Tabu is no glib mash-up straining only for superficial effect; its rich array of connections and ambiguities draws the viewer in, creating an allusive yet human drama that’s immersive and rewarding.

Oh, and it’s just beautiful. Academy ratio, no less. Black and white in both 35mm and 16mm stock. Grain you want to reach out and touch. No wonder Gomes is the talk of the festival circuit, since this highly original assemblage is so obviously the real deal.

Agreeably, the film also seems determined not to take itself too seriously, something that’s evident from the quirky colonial-era prologue, in which a 19th-century Portuguese explorer in safari gear traverses distant grasslands with native bearers in tow. Ostensibly his purpose is the further glory of God and king, but the voiceover reveals a more private truth – he’s trying to put distance between himself and the image of his beloved late wife back home.

Not too successfully either, as it turns out, since her unquiet spirit accompanies him. Indeed, even after he’s committed suicide by throwing himself to a lurking crocodile, the ghost and the croc sit side by side on the riverbank, destinies entwined. “You cannot escape your heart,” the apparition warns us, setting a thematic agenda for the rest of the proceedings, where outward behaviour will often seem at odds with individual emotional imperatives.

That’s certainly the case in the first-up present-day Lisbon section of the story, which Gomes titles ‘Paradise Lost’. Pilar (Teresa Madruga), a middle-aged spinster, deals with her loneliness by concerning herself with the plight of her elderly neighbour Aurora (Laura Soveral), who may be in the early stages of dementia and is convinced that her black maid Santa (Isabel Cardoso) is using witchcraft against her.

A magnificent nocturnal shot of Pilar tells us everything about this woman – as she stands on her apartment balcony a fringe of light silhouettes an otherwise pitch-black profile, suggesting a truly hollow individual. Professionally, she works as a human-rights lawyer investigating third-world injustices, again hinting at someone turning their focus on far-off climes to escape their everyday sufferings closer to home. Given that Portugal was the last of the European nations to relinquish its grip on its former African territories, are we to assume that the very notion of looking geographically outwards for self-definition is still somehow ingrained in the national consciousness?

Aurora, the representative of an earlier generation, is revealed in the course of the story to be even more marked by her time in Africa. At first her patronising attitudes to her servant offer up a reminder of the bad old days, but in the second section of the film – portentously dubbed ‘Paradise’ – the revelation of her personal history shows her own early 1960s colonial experience as a liberation from the moral strictures of bourgeois convention.

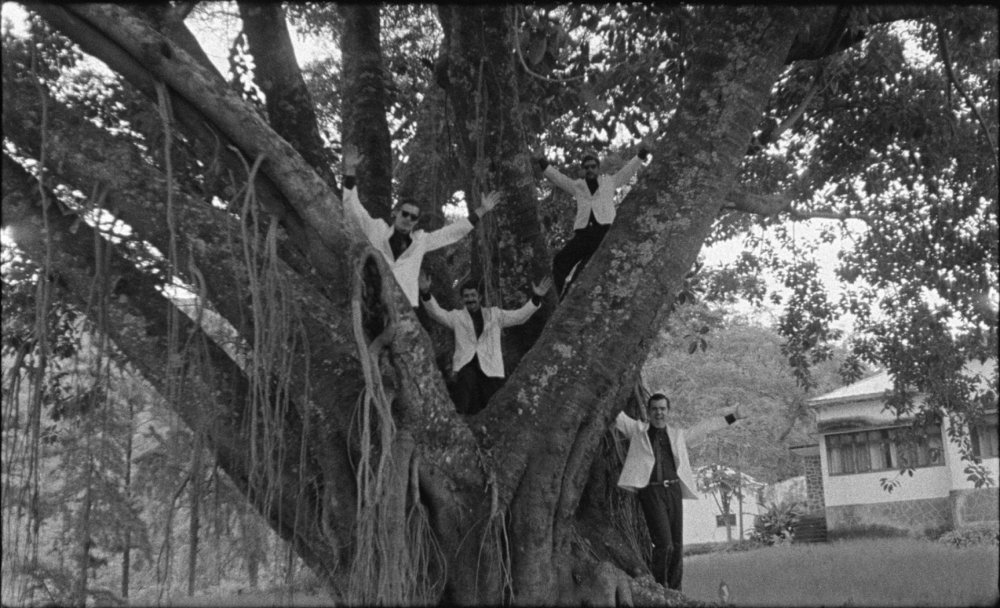

The taboo that’s broken here is the sanctity of marriage, as the younger Aurora (Ana Moreira) dallies with the rakish Gianluca (Carloto Cotta), who lives on property neighbouring her husband’s tea plantation, their initial assignation facilitated, significantly no doubt, by the timely escape of her pet crocodile. Ensuing events take the mood in the direction of florid melodrama, expressively (and in temporal and geographic terms) a world away from the constricted, somewhat doomy austerity of the Lisbon opener.

As Gomes indicated in his splendid breakthrough feature Our Beloved Month of August (2008), he’s a man for a bit of bifurcation. In that instance, there was a magical moment of transition between factual and fictional registers, when what seemed to be a documentary about a shambling rural film shoot elided into a romantic drama in which the real people we’d met on location played versions of themselves.

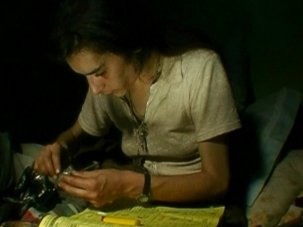

This time round, at about the halfway mark, the story shifts into what we initially read as a flashback to Aurora’s rather scarlet past, but there’s also a startling formal transformation to underline the point. While Pilar’s sufferings are laid out with an almost anonymous severity, cut to the young Aurora in Africa and we’re in another cinephile universe, a sort of netherworld between the silent and sound eras, where the elderly Gianluca’s exquisitely literary voiceover shapes the telling of events. What’s more, although we can hear the background ambience and music, the individuals’ dialogue is reduced to silence – an effect richly evocative yet at the same time disorienting.

At this point one’s critical duty is to trot out the Murnau references inherent in the film’s title (Murnau and Robert Flaherty’s jointly authored 1931 South Seas saga of the same name) and elsewhere (we even visit the Sunrise old folks’ home), although the substance of what we see is rather more redolent of any number of exotic tales from golden-age Hollywood, from 1930s fare such as Trader Horn and the Weissmuller Tarzan flicks through the decades to the likes of Mogambo (1953).

Moreover, while it’s true to say that the Academy-ratio framing and ace cinematographer Rui Poças’s deliciously grainy 16mm black and white proclaim a certain vintage quality, the sundry tracking shots, moments of slow motion and flashes of nudity all speak in a cinematic language that’s much more modern. A composite of cinema and memory, perhaps? Maybe even the movie that’s playing in Pilar’s head? After all, we know she’s listening to Gianluca tell his and Aurora’s story, we’ve already witnessed her crying at the pictures, and there’s a certain music cue (a kitsch Euro-cover of Phil Spector’s ‘Be My Baby’) linking both sections of the film.

On a first viewing this cross-referencing is undeniably dizzying, even as we wallow in just so many moments of sheer pictorial beauty (especially in the brilliantly cast segment ‘Paradise’, where co-stars Moreira and Cotta really do look as if they’ve just wandered off the RKO backlot). Daringly, Gomes leaves us to make the connections that will not only complete the story – will Pilar be a changed woman, knowing how Aurora remained to some extent a prisoner of her past? – but also tease out its many thematic implications, yet that seeming lack of resolution is absolutely central to the intoxicating sense of textural and textual richness this remarkable film presents to us.

Experts in Portuguese national cinema will no doubt find points of contact with the likes of Manoel de Oliveira and Pedro Costa, for so long the country’s international standard bearers, but at the risk of making a sweeping generalisation, the quintessentially Portuguese notion of saudade – that longing for a return to a lost happiness which can never be regained – surely offers an entry point to Tabu’s historical, cultural and emotional labyrinth.

Old Hollywood, the colonial era, Phil Spector’s wall-of-sound mono heartbreakers, Academy-ratio black and white… What are they all but emblems of that which is gone forever? The past isn’t just a foreign country in this instance; it’s an old movie, a period pop song, the passions of youth. And it can only return in the mists of longing and memory, those refractions shaped by emotional need, which continue to envelop and inform lives such as Pilar’s and Aurora’s. Lives perhaps – Tabu tantalisingly poses the question – more like our own than we’d care to admit?

Further reading in the September 2012 issue of Sight & Sound

White mischief

Miguel Gomes discusses his playful and idiosyncratic poetry with Mar Diestro-Dópido.

And on Sight & Sound online

Silver valentine: Miguel Gomes’s audacious movie medley Tabu

Nick James blogs on the Berlinale premier of the Portuguese former critic’s intricate, near-transcendental homage to film history (February 2012)

Review: Our Beloved Month of August

A family musical docu-drama set amongst Portuguese village-fête show bands, Miguel Gomes’ film is a hybrid work of bewitching perversity, says Jonathan Romney (January 2010)

Serenity

Miguel Gomes explains how Pedro Costa found a home to film as his own with the inhabitants of Fontainhas on the margins of Lisbon (September 2009)

-

Sight & Sound: the September 2012 issue

In our redesigned, expanded new issue: The Greatest Films of All Time by 846 critics and 358 directors. Plus more pages, sections and columns, and...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.