At this year’s Venice film festival, three titans of American documentary filmmaking presented works which dug into the national psyche with varying degrees of depth. The lengthiest of these was 83-year-old Frederick Wiseman’s At Berkeley, a forensic and immersive 244-minute study of the famously sprawling California university. It’s the latest in Wiseman’s series of films about institutions following the likes of High School (1968) and State Legislature (2007) and, as it gradually unfolds, posits Berkeley (revealed to be facing severe ‘disinvestment’ in public funding from the state) as a microcosm of American society at large.

70th Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica la Biennale di Vienezia

28 August-7 September 2013 | Italy

Crafted in the director’s familiar understated and unobtrusive style (no voiceover; minimal music cues and camera movement), it consists of long, talk-heavy sequences in classrooms, offices and boardrooms, punctuated by brief montages depicting serene everyday life on the leafy campus, or musical and theatrical performances. Despite its intimidating length, Wiseman’s structure – created entirely in the edit – fosters a set of hypnotic internal rhythms, allowing the viewer space to make their own thematic connections.

A narrative of sorts gradually emerges surrounding the efforts of the UC Berkeley administration to prepare for, and deal with, a large-scale student protest in response to fee hikes. However, At Berkeley is really about two things: firstly, the power and importance of open communication, making it, by extension, a quietly patriotic hymn to American democracy; secondly, it is self-evidently a vigorous and rousing defence of higher and public education in economically straitened times.

The footage Wiseman captures of in-depth discussions are uniformly riveting, from fly-on-the-wall observations of high-level administrative decision-making to sequences of students from various backgrounds honestly debating issues of class, race and wealth. Only one thing gnawed at me: within Wiseman’s socially panoramic gaze, I wondered if we might have heard from the university’s custodial staff – the working classes operating at the ground level. Instead these figures (a Latina leaf blower; a black janitor) are only seen as voiceless ghosts, utilised as decorations in connective scene-tissue. But this is a minor quibble about a richly detailed, microcosmic and truly engrossing work.

“One of the worst problems for people in positions of formal authority is that they don’t get good feedback”, a PR specialist tells a classroom of students in At Berkeley. One wonders whether Donald Rumsfeld, former US Secretary of Defence, and the subject of Errol Morris’s The Unknown Known, ever had anyone to tell him that his special brand of neo-Orwellian alphabet soup (from which the film’s title is extracted) would do his reputation few favours?

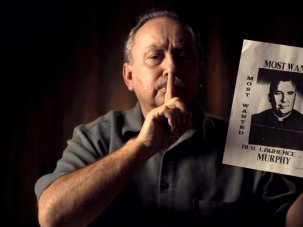

The Unknown Known

Taking the form of an extended interview interspersed with archival footage, and visually enlivened by the occasional infographic, the film is a sober and moderately engrossing portrait of a key figure in the recent political landscape. Morris, a far more reflexive and present filmmaker than Wiseman, is more restrained than usual, and questions Rumsfeld in an oddly jocular style. Perhaps this approach was a last resort after more concerted initial efforts? For the flinty, 81-year-old Rumsfeld (whose rictus grin remains ever-present) is giving nothing away.

The film’s most interesting content is not to be found in the airless, non-revelatory discussions about post-9/11, Dubya-era America (Rumsfeld holds depressingly but predictably fast on WMDs, Saddam Hussein and Guantanamo, even when faced with evidence to contradict his assertions), but rather on his meteoric ascent through the Washington power structure, beginning in the 1960s. Constructed from a patchwork of Rumsfeld’s memos, often read aloud by the man himself, and reams of archive material and photography, these passages paint a picture of a canny player with an inscrutable plan. We discover that Nixon hated him (“I think Rumsfeld may not be too long for this world”, he is heard to say), and it is quite something to see young Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney plotting away together as early as the early 1970s; it gives one a tangible sense of how deeply embedded the American political network really is.

Yet, though watchable, the film pales in terms of enjoyment and insight in comparison to Morris’s last film interview with a former Defence Secretary, Robert S. McNamara, in 2006’s The Fog of War. There’s no revelatory smoking-gun moment or explosive confrontation, and it’s difficult to imagine that anyone could come away from it with a radically different opinion on Rumsfeld or his policies than they held already. Over and above everything else, Morris’s film is a documentary about a documentarian. Rumsfeld explains how he has systematically written and recorded “millions” of memos (or “snowflakes”, as he calls them) over the years, and the lasting impression given is of a calm, calculating individual who has painstakingly attempted to control his own legacy.

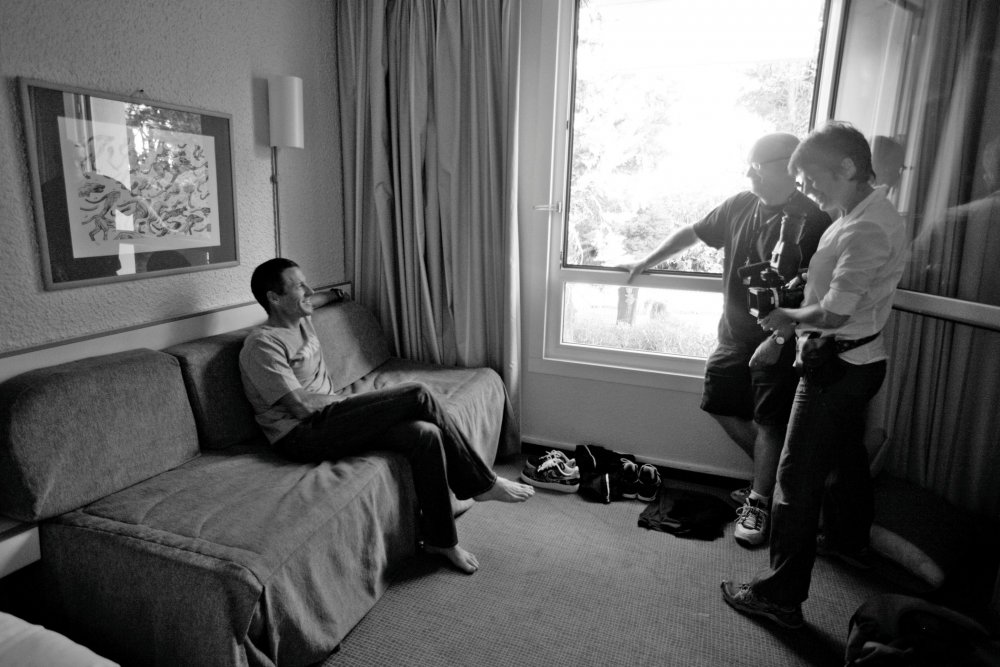

The same can be said for Lance Armstrong, the disgraced former cyclist and subject of Alex Gibney’s The Armstrong Lie. Gibney had been filming a documentary on Armstrong’s unexpected comeback to professional cycling in 2009 following his successful battle with cancer, but it had to be shelved when the controversy over Armstrong’s alleged doping exploded.

The Armstrong Lie

Understandably piqued about being lied to, Gibney demanded to reinterview Armstrong this year, shortly after he had come clean on the Oprah Winfrey show. Gibney’s key question is, simply, why on earth did Armstrong attempt to come back when he’d already secured his place in the nation’s hearts?

The answer appears to be that Armstrong simply couldn’t help himself, although this angry film’s biggest revelation is that the world of cycling was, in Armstrong’s time, crooked to the core; this much is admitted by the host of ex-professional cyclists who testify to Gibney, and assertions are supported by a convincing selection of evidence from journalistic contributors.

Why is cheating rife? The consensus seems to be that cycling (in particular the Tour de France) is the most punishing sport in the world, and that illegal substances are necessary to augment the body through such times of stress. Accordingly, a moral relativism sets in: as Irish popsters The Cranberries once questioned, everybody is else doing it, so why can’t we? What distinguished Armstrong was, of course, his rampant success, his brass-necked, bulletproof self-assurance, and the too-good-to-be-true, American Dream narrative of his comeback from cancer (not to mention his roots as a poor scamp from Texas who never met his father).

The Armstrong Lie is always compelling, and Gibney deserves credit for putting his own naiveté up on the screen for the world to see. He openly admits, with a hint of self-disgust in his voice, that he too was taken in by Armstrong’s sheer brio (he even includes a picture of himself goofily posing for the camera in a race that Armstrong was later found to have cheated in.)

Yet when the credits roll, Armstrong remains a flinty-eyed enigma, and it also becomes clear that Gibney’s latent affection for his subject has stopped this film being the big takedown that would have been so satisfying. In this respect, it simultaneously echoes Morris’ inability to get a real rise out of Rumsfeld, and underscores the seductively compelling power of the big American lie.

Further viewing

Fred Wiseman talks Crazy Horse with Edward Lawrenson

(16:00)