In Taxi to the Dark Side (2007) documentarist Alex Gibney started out with a microcosm – the death in custody of a single suspect at Bagram airbase in Afghanistan – and steadily widened out to take in a culture of complicity in torture, and public denial of that complicity, which extended into the highest levels of the Bush administration.

USA/Ireland 2012

Certificate 15 106m 48s

Director Alex Gibney

Voice cast

Terry Jamey Sheridan

Gary Chris Cooper

Pat Ethan Hawke

Arthur John Slattery

narrator Alex Gibney

In Colour

[1.85:1]

Distributor Element Pictures Distribution

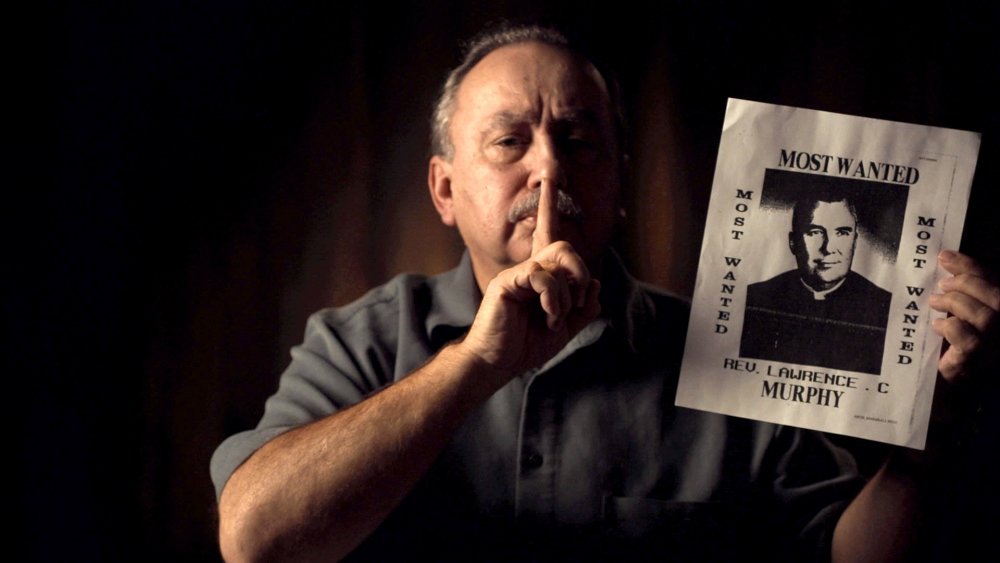

Gibney adopts a parallel narrative pattern in Mea Maxima Culpa, taking as his starting point four former pupils at the St John’s School for the Deaf in Milwaukee trying to alert the Church authorities to the abuse they suffered at the hands of the school’s director, Father Lawrence Murphy. From here he gradually widens his focus to show how evidence of similar cases in countries around the world was at first suppressed, then angrily denied, and finally reluctantly and patchily admitted by the Vatican.

We’ve been here before, of course – in Amy Berg’s similarly themed Deliver Us from Evil (2006), for instance. But there’s an added level of repugnance about Murphy’s crimes, in that these were deaf kids, all the more isolated and vulnerable, often with non-deaf parents who didn’t know signing – so that Murphy, who wasn’t deaf but could sign, served as their only channel of communication.

Behind him loomed the monolithic power of the Catholic Church, presenting a united front of sanctimony and outrage in the face of allegations, making its accusers feel guilty and ashamed and, with its insistence on priestly celibacy, creating a perfect forcing ground for abusers of this stamp. In the words of Richard Sipe, a former Benedictine monk and mental-health counsellor: “The system of the Catholic clergy… selects, cultivates, protects, defends and produces sexual abusers.”

As several participants in the film observe, even when Church authorities finally concede that abuse has taken place, it seems their prime response is always to lament that a Catholic priest should have transgressed so woefully, rather than to express any compassion or contrition towards the victims. In the wake of the arrest of the Irish cleric Father Tony Walsh, known to the Church authorities for 20 years as a serial abuser (and one of the very few priests to stand trial for the offence), we see his boss Desmond Connell, the then Archbishop of Dublin, asked why he never thought to visit or even contact any of those Walsh abused. Connell’s wet-eyed response, breathtaking in its inadequacy, is: “I suppose I should have done – but I’ve so much to do.”

As in Taxi and his other documentaries, Gibney piles up the evidence with scrupulously detailed research, always keeping himself behind the camera. The film’s only weakness is the frequent reconstructions of the St John’s abuse scenes, presented like clips from horror movies with insidious music and blood-red backlighting.

It’s also slightly disconcerting to have the signers’ ‘words’ spoken in the familiar tones of John Slattery, Ethan Hawke, Chris Cooper et al; subtitles might have worked better. But these are minor flaws in a film that meticulously assembles an impressive range of evidence, including interviews, documents, photographs and home movies, to paint a devastating picture of an institution still, even after all the revelations and some $2 billion paid out in damages, far too fixated on its own supposed sanctity.

-

Sight & Sound: the March 2013 issue

Gael Garcia Bernal in Pablo Larraín’s No, plus Caesar Must Die, Somersault, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Montgomery Clift.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.