When you think what the British admen of the 1960s and 1970s brought to the cinema when they began making feature films, their Chilean equivalent Pablo Larraín looks like some kind of master. The Club is an intensely serious drama about the fallout from the paedophile-priest scandals that have destroyed so much faith in the Catholic Church worldwide. The script is entirely fictional, but Larraín stresses that secret house-prisons for delinquent priests like the one shown in the film do exist, in Chile and elsewhere. What disturbs him most is that the Church cares less for its victims than about saving face and concealing scandal – in a word, safeguarding its own ‘infallibility’, the issue at the core of the film.

Certificate 18 95m 6s

Chile/France 2015

Director Pablo Larraín

Cast

Father Vidal Alfredo Castro

Sandokan Roberto Farías

Sister Mónica Antonia Zegers

Father García Marcelo Alonso

Father Silva Jaime Vadell

Father Ortega Alejandro Goic

Father Ramírez Alejandro Sieveking

Father Lazcano José Soza

Father Alfonso Francisco Reyes

In Colour

[2.35:1]

Subtitles

Chilean theatrical title El club

UK release date 25 March 2016

Distributor Network Releasing

networkonair.com/features/the-club

► Trailer

The title is sardonic. This ‘club’ is not formally constituted and has few rules. Its members are Catholic priests who have been caught sexually abusing young boys. Rather than defrocking them or allowing them to go to trial, the Church has whisked them out of sight to an anonymous house in a remote seaside town, in effect an open prison which they can leave only for a few hours in the early morning and early evening.

This cloistered enclave is disrupted twice, first by the arrival of new ‘inmate’ Father Lazcano, who kills himself on his first day there, and then by the arrival of earnest young priest Garcia, who is ostensibly investigating the suicide but has actually been charged with finding a way to close the place down. The figure who proves central to both disruptions is Sandokan, a mentally unstable man who was sexually abused by Lazcano many years earlier and has followed him from place to place ever since.

Sandokan is central because he’s an embarrassing paradox: a victim whose graphic descriptions of what Lazcano did to him can expose what the house is and why the priests have been secluded there, but also a believer in the Church’s dogma about the sanctity of its priests. Sandokan considers himself touched by God, since whatever a priest emits is by definition holy. (He has occasional sex with women prostitutes, but considers that “dirty”.)

Sandokan was in fact destroyed by being sodomised as a boy; he lives in misery and chaos, sustained by massive daily doses of tranquillisers, painkillers and uppers. His pursuit of the priest who violated him (this is what provokes Lazcano’s suicide) is a quest for the ‘purity’ that has been missing all his adult life. Garcia’s ultra-pragmatic solution to the problem of the house – of course, it’s the house’s very existence that is the fundamental problem – is to put Sandokan in charge, creating a perfect huis clos that will damn everyone in it to lifelong torment.

As an account of what the Church will do to protect itself, the film should ideally be double-billed with Alex Gibney’s excellent documentary Mea Maxima Culpa (2012), which explores the heretical belief that an ordained man becomes intrinsically holy. Father Garcia, the Church’s fixer, who may or may not be gay himself but has clearly held to his vow of celibacy, is in turn bemused, horrified and baffled by what he hears in the house. Larraín constructs two quite lengthy montage sequences from his sessions questioning the four priests, building not only a picture of their denials and self-delusions but also something more insidious: when the senile Father Ramirez, the oldest ‘inmate’, begins repeating the words he heard from Sandokan about how hard it is for a small boy to fellate a grown man, Garcia wonders aloud if he’s describing a fantasy.

But it’s not the absence of penitence that ultimately pushes Garcia into extremist action. Only when the warden Sister Monica (herself compromised by a history of beating the African child she adopted) threatens to go to the press does Garcia come up with the berserk idea of killing all the town’s greyhounds, simply to snatch away the pleasure the priests take in dog-racing. Buñuel would have understood.

On this evidence, nobody is likely to hail Larraín as a great visual stylist. His Scope compositions are unadventurous and his film language and editing syntax are fundamentally orthodox. The climactic crosscutting between two acts of violence seems to spring from an impulse to produce a ‘punchy’ finale; all it actually brings to the film is a redundant hint of melodrama. But The Club is written and acted with great skill and remarkable sensitivity to the warped thought processes of paedophiles and their victims. Catholics are not its only audience.

In the April 2016 issue of Sight & Sound

Pablo Larraín discusses The Club’s compassionate, claustrophobic study of human frailty, and its grainy moral and celluloid gloom, with Mar Diestro-Dópido.

→ Buy a print copy

→ Access the digital edition

→

Also recommended this week

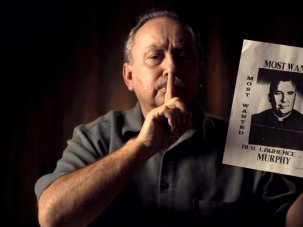

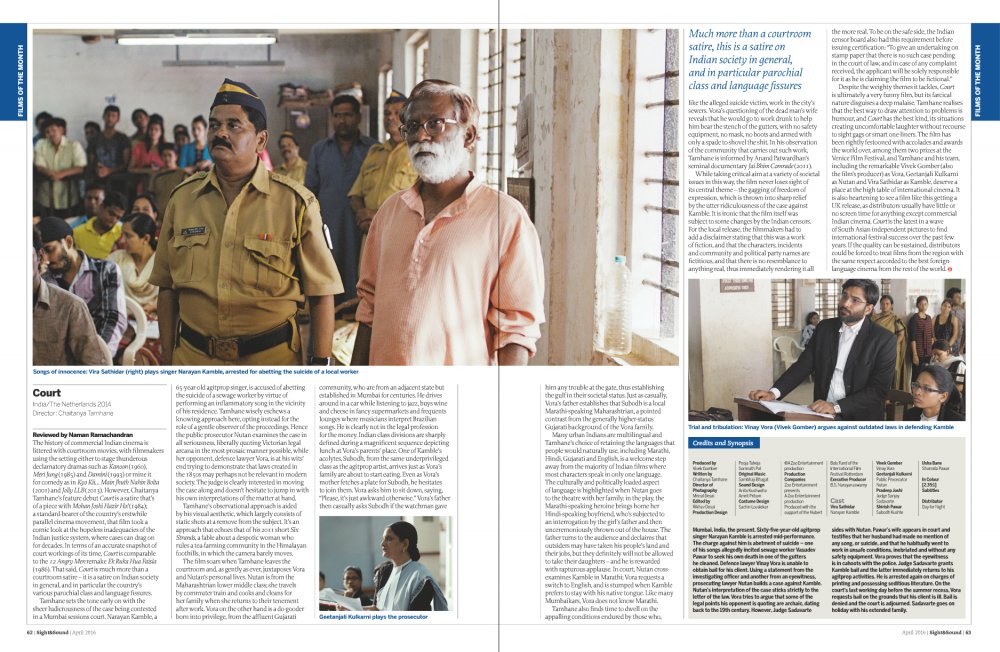

Court

Director Chaitanya Tamhane | India 2014 | On road-show release

day-for-night.org/court-film | ► Trailer

The latest in a wave of South Asian independent films to find festival success, a satire of a farcical court case that opens up to lampoon Indian society and its class and language fissures. Chaitanya Tamhane is interviewed by Charles Gant in our August 2015 issue, and the film is reviewed by Naman Ramachandran in the same issue:

“Despite the weighty themes it tackles, Court is ultimately a very funny film, but its farcical nature disguises a deep malaise. Tamhane realises that the best way to draw attention to problems is humour, and Court has the best kind, its situations creating uncomfortable laughter without recourse to sight gags or smart one-liners… If the quality can be sustained, distributors could be forced to treat films from the region with the same respect accorded to the best foreign-language cinema from the rest of the world.”

and

Zootroplis

Directors Byron Howard, Rich Moore | USA 2016 | On wide release

movies.disney.co.uk/zootropolis | ► Trailer

Set in a bustling megalopolis in which, in the absence of humans, mammals have evolved their own multi-species civilisation and rub along not always harmoniously, Disney’s latest hit animation is a bright, brash and witty paean to diversity in the form of a 48 Hours-style detective foray, partnering a can-do rookie rabbit from the sticks with a sly-hustler fox. Reviewed by Andrew Osmond in our forthcoming May 2016 issue.

and

Speed Sisters

Director Amber Fares | USA/Palestine/Qatar/Denmark/United Kingdom | On limited release, DVD and VoD

dogwoof.com/speedsisters | ► Trailer

A documentary about a team of female racing drivers in Palestine, as teeming with personal sympathy for its five protagonists as it is with political issues. Reviewed by Lisa Mullen in our August 2015 issue:

“If, at times, the film seems too crammed with storylines and incidents, it nevertheless manages to be a fascinating tribute to the indomitability of youth and aspiration. Any ambitious young person anywhere will face problems, Fares seems to say. It’s just that, in Palestine, there are a lot more bumps in the road.”

-

Sight & Sound: the April 2016 issue

Tom Hiddleston and the cast and crew of High-Rise talk class and violence past and future – and the rise of cinema’s Ballardian worldview....

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.