Web exclusive

Mea Maxima Culpa

I don’t know what truth is. Truth is something unattainable. We can’t think we’re creating truth with a camera. But what we can do is reveal something to viewers that allows them to discover their own truth

—Michel Brault

There’s a thread of documentaries in this year’s London Film Festival in which American filmmakers attempt to communicate some kind of truth about landmark crimes and injustices in their country. The best pay as much attention to the grey in-between as to the black and the white but all, to varying degrees, shed light on the intricacies of the US justice system, and examine the crucial role of the media in shaping perceptions of different cases.

To begin in Wisconsin (though the film ultimately looks uneasily around the world), Alex Gibney’s well-researched and -structured Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God is an expansive, clear-eyed investigation of widespread child abuse in the Catholic Church (and the director’s best film since 2007’s Taxi to the Dark Side).

It starts in 1972, with what the director found to be the first publicly registered report of abuse in the American Church. For over 25 years at St John’s School for the Deaf in Milwaukee, father Lawrence C. Murphy got away with sexually abusing vulnerable pupils. Despite warnings by American archbishops, and a sustained campaign of protest from his victims, Murphy was simply relocated to different parishes and allowed to continue his crimes.

Using extended – and deeply moving – interviews with deaf survivors (voiced emphatically by the likes of Chris Cooper and John Slattery), Gibney details how the Wisconsin boys’ trailblazing attempts at seeking justice were countered by a pernicious combination of clerical obfuscation, millions of dollars’ worth of mysterious settlements and a municipal system unprepared to deal with such organised institutional resistance.

The film then travels to Ireland, and later Italy and the Vatican itself, to illustrate the sheer breadth and depth of the corruption. Revelatory on the troubling intersection of law and faith, Mea Maxima Culpa offers persuasive evidence that the Church is unlikely to address its problems without being actively made to by governments that answer not to God but to regular citizens. As it is, the Pope (and Gibney fearlessly implicates the last several of them) cannot be judged by any civil authority: he’s literally and figuratively above the law.

West of Memphis

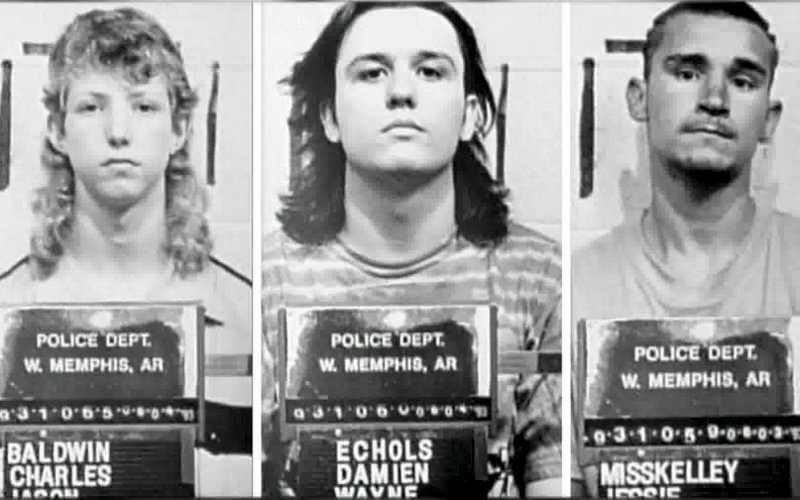

Child abuse in the Catholic Church was the subject of Amy Berg’s Oscar-nominated Deliver Us from Evil (2006). Her follow-up is the exhaustive and exhausting 150-minute activist doc West of Memphis, which focuses on a grisly 1994 case in West Memphis, Arkansas, when three teenagers – Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley – were arrested for the murders of three eight-year-old children. The local judicial system, eager for an open-and-shut case, callously exploited the teens’ interest in the occult to cast them as psychotic devil-worshippers. The three were subsequently convicted of murder and spent more than 18 years in prison before being released (and in an almost tragicomic instance of legal bureaucracy, they had to trade guilty pleas for their freedom).

Berg’s muscular, propulsively edited film is at its strongest in painting a portrait of a local legal community which shamelessly colluded in ostracising the suspects for their outsider status. The venal political self-interest, augmented by damning archive footage and testimony, is shocking. It’s also a fascinating case study of the oft-maddening intricacies of the law and, as the film puts it, the necessity for “crowd-sourced criminal investigation”. To wit: if the state Justice Department won’t do it’s job, the public will just have to do it for them.

The film’s most shocking element is its focus on the uncle of one of the victims – Terry Hobbs, who has since become the chief suspect. While the evidence compiled against him is convincing, there’s something unsettling about the manner in which it’s communicated. For example, there’s an unforgivable sequence which utilises exactly the same type of emotive shock tactics (a rapidly edited montage of graphic murder photographs) it derides the initial prosecution for using.

Produced by film director Peter Jackson and Echols himself, and featuring several impassioned celebrity contributions (including Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder and hardcore rocker-turned-poet Henry Rollins), the film has a particular sweep and glamour, although the subject has already been covered at length and in detail in Joe Berlinger’s superb Paradise Lost trilogy (given only a brief mention here).

The Central Park Five

Another dreadful miscarriage of modern American justice is the focus of veteran documentarian Ken Burns’ rigorous The Central Park Five.

In a crime-ridden late-80s New York sharply divided across class and racial lines, an incident occurred that shocked the city. A 28-year-old white female jogger was brutally raped, beaten and left for dead in Central Park. Despite a complete lack of evidence, five black and Puerto Rican youths (aged between 14 and 16) who’d in been in the park that evening were charged with the assault, shamelessly coerced and manipulated into confessions by NYPD homicide detectives, and finally imprisoned. Their release in 2002, instigated by a belated confession from the real culprit – rather than a sustained campaign of activism – was met with nothing like the sort of fanfare that’s accompanied the West Memphis Three.

The Brooklyn-born Burns is clearly at home with the subject, and in using a broad cross-section of articulate contributors, archive footage and evocative locally-themed art (including Bruce Davidson’s stunning subway photographs), expertly draws the tinderbox socio-political context of New York in 1989. Then-mayor Ed Koch, a key architect of the vicious media campaign to defame the boys, offers his brashly venal opinions, while NYC prosecutors and police (perhaps unsurprisingly) declined to comment at all. It makes for a pretty damning picture of what was a proxy war in a fiercely right-wing era, with the lives of the five on the front line.

The most disturbing aspect of Burns’ film though is the suggestion that the boys’ incarceration, however unjust, somehow made a depressed New York feel better about itself. Far from a triumphalist account of a reversal of fortune, The Central Park Five is a chilling piece of work that asks America to hold a mirror to itself and look at how it treats its young dispossessed. The film also keenly illustrates how the wrong crime in the wrong place can trigger a nationwide symposium on racial issues. (The shooting of unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin in February 2012 is the latest such incident to provoke such a reaction.) There was one an upside to the story: the eventual full recovery of the jogger, Trisha Melli.

Free Angela & All Political Prisoners

Almost 20 years earlier, social activism was coursing through America’s blood, and a key individual in this landscape was teacher/radical/intellectual Angela Davis. A one-time Black Panther leader, Davis also held membership of the Communist Party, leading to California Governor Ronald Reagan’s successful request in 1969 to have her barred from teaching at any university in the state. Soon after, she was tried and eventually acquitted of suspected involvement in the August 1970 abduction and murder of a California judge.

Directed by Shola Lynch, Free Angela & All Political Prisoners is a hugely enjoyable if selective documentary which cannily combines a portrait of the woman and her times (conservative Nixonian America) with a compelling court-case thriller narrative. With an accent on black political consciousness, and the growing presence of black professionals in the field of law, it’s both an upbeat tribute to political dissidence and free speech and a treatise on the potential for the positive intersection of law and activism. The preternaturally composed Davis also features as a present-day talking head.

Yes, it’s pretty one-sided – but the title pretty much lets you know what you’re in for. The film is also tainted by some unnecessarily slick reconstructions and wildly intrusive music. Yet the positives outweigh the negatives, and as a bonus there’s some astonishing archive footage of French writer Jean Genet launching into a furious broadside against American exceptionalism after Angela’s initial capture.

Bayou Blue

In contrast to the verve of the above, Alix Lambert and David McMahon’s Bayou Blue is a perfunctory account of a series of crimes that haunted the bayou area of Houma, Louisiana between 1997 and 2006, when Ronald Dominique raped and murdered 23 young men – mostly poor local blacks.

What makes Bayou Blue such a disappointment is its shyness in engaging with the broader context of the case. Why was such a horrific series of incidents so comprehensively ignored by the media? The devastating and distracting effect of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill are tentatively raised, as is the suggestion that the victims, as ‘street people’, weren’t of any great importance. Asked why the case received no national attention, a local journalist responds: “I don’t know. But let me know if you find out”. Surely this is the job of the filmmakers?

Instead the majority of the film’s 80 minutes is taken up with repetitive procedural explication from police who worked on the case. Bayou Blue is further hampered by a jumbled narrative structure, and an over-reliance on inarticulate contributors. One cultural issue that’s touched on, but frustratingly not really explored, is the steadfast refusal of some family members to accept that their departed may have been homosexual. Still, missed opportunity as the film may be, it does at least shed some light upon this depressed community and the outrages which plagued it over a distressingly long period of time.

← Previous: The week-one whirligig

Next: Rebel charm – Benh Zeitlin on Beasts of the Southern Wild →

In print

- Alex Gibney talks to Nick Bradshaw about Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer and Casino Jack and the United States of Money on page 10 of the April 2011 issue of Sight & Sound (via our Digital Archive).

- Taxi to the Dark Side is reviewed on page 77 of our July 2008 issue (via our Digital Archive).

- Joe Berlinger talks to James Bell about Paradise Lost and its sequel on page 87 of the July 2005 issue (via our Digital Archive).

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.